The U.S. Library of Congress recently digitalized a series of handwritten and photocopied memoirs and biographies of 80 Soviet-Koreans, noting their contributions to, and sacrifices for, the establishment of North Korea. Concurrently, North Korea held its latest military parade on the morning of September 9 to commemorate the 73rd anniversary of its founding. While Pyongyang touts its reclusive nature as an act of national pride free from foreign influence, the reality is that a collection of outsiders – Soviet-Koreans, in particular – helped establish the country’s government and institutions still in place today despite claims of complete self-reliance.

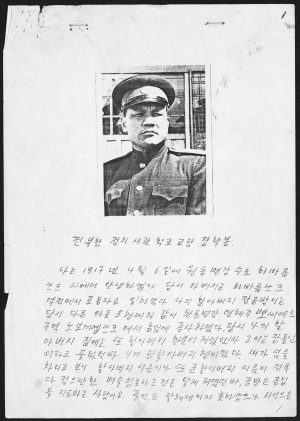

The most notable contribution to the digitalized collection is the handwritten account of Jang Hak-Bong entitled “History Written By Our Blood and Tears.” According to Voice of America, Jang previously served as the first head of the North Korean Ministry of Foreign Affairs, as well as the commander and director of operations for the Korean People’s Army, making him one of the highest ranking Soviet-Koreans within the North Korean government. However, even rising to the highest echelons of North Korean society couldn’t protect Jang from accusations of cultural and ideological weakness due to his mixed upbringing, which Kim Il Sung cited as the reason for his forced repatriation back to the Soviet Union during the 1950s.

The Korean diaspora spans across the globe. Starting around the 1860s, Koreans started to establish communities in the Russian Far East with a rapid increase following aggression from Imperial Japan culminating in the colonization of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 to 1945. However, the Soviet Union imposed a mass deportation of approximately 200,000 ethnic Koreans living in the Russian Far East to Central Asia in 1937 where many perished due to harsh and inhospitable conditions.

During the early years of the Cold War, the Soviet Communist Party sent ethnic Koreans living in the Soviet Union – mostly Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and modern-day Russia – to North Korea to help establish and administer the North Korean government and its institutions to ensure the successful spread of communism throughout the region. Once referred to as Soryeonpa, but now commonly called Koryo-saram or Koryo-in, Soviet-Koreans formed a significant portion of Pyongyang’s first class of elites within its political caste system. However, Kim Il Sung decided to purge the Koryo-in, as well as other faction groups such as the Yeonanpa, who supported the Chinese Communist Party, during the late 1950s to early 1960s in an effort to consolidate his power as the Eternal Leader of North Korea void of any subjugation, or indebtedness, to a foreign power.

These discriminatory purges would later mirror the North Korean ideology of Juche often translated as “self-reliance” which its original architect-turned-defector, Hwang Jang-yop, described as an ideological weapon intended to purge Kim Il Sung’s political rivals, diminish foreign influence on domestic North Korean affairs, and justify a hereditary power succession system which continues to rule the country today.

The U.S. Library of Congress’ decision to publish and digitalize Soviet-Korean memoirs recounting their lives as both communist heroes and banished outsiders will provide scholars of Korea with deeper insight into the complexity of Korean identity and the internal power struggles leading to the creation of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). For a reclusive and isolated country like North Korea, this form of primary documentation is crucial to understanding the ambiguity of “self-reliance” and its political malleability to justify the purging of any individual, ideology, or influence which could possibly pose a threat to the legitimacy of the Kim regime.