One of the less heralded recent aspects of the COVID-19 story in Southeast Asia has been Cambodia’s remarkable success in vaccine distribution. As of September 6, just over two-thirds of the country’s population had received at least one dose of vaccine, while 53 percent were fully vaccinated. This is the highest number in Southeast Asia outside wealthy Singapore, which has now fully vaccinated more than three-quarters of its population.

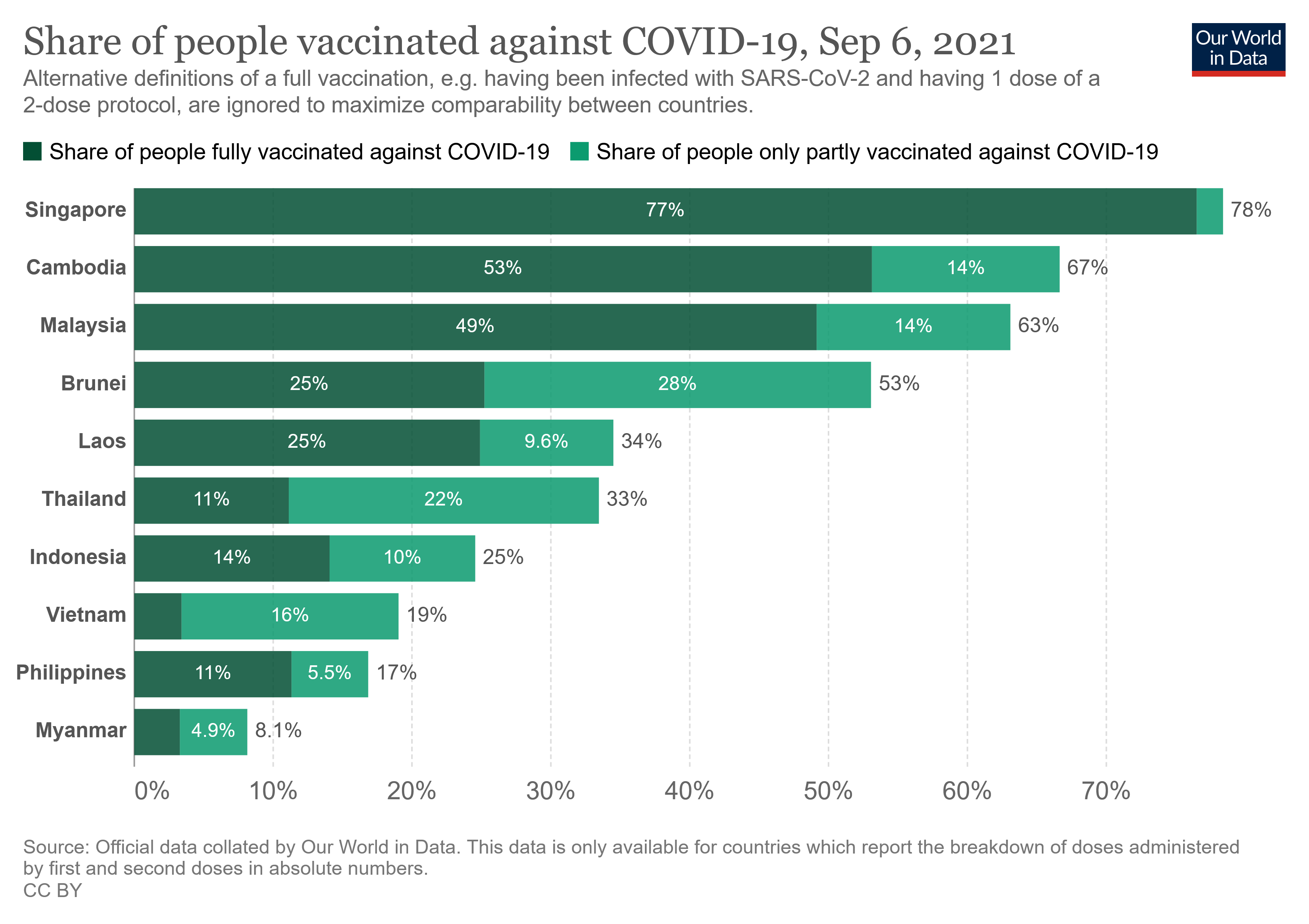

It also compares strikingly well to Cambodia’s wealthier neighbors, including Malaysia (49 percent fully vaccinated), Brunei (25 percent), Thailand (11 percent), and Vietnam (3.4 percent). (All of these figures are available via Our World In Data.)

As one would expect, vaccination levels in Southeast Asia roughly correlate to levels of economic development. Cambodia is the exception: the nation with the second lowest per capita GDP in ASEAN, it is also, as mentioned above, the nation that has the second highest per capita vaccination rate.

To be sure, the country’s broader response to COVID-19 has had a range of negative side-effects. As in many places, Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government has used COVID-19 as a pretext to pursue political vendettas against government critics including critical journalists and members of opposition parties. According to Human Rights Watch, the Cambodian authorities have arrested dozens of people for expressing critical opinions about the government’s COVID-19 response.

Moreover, during lockdowns in April and May, the government introduced restrictions that reportedly cut off food supplies for tens of thousands of garment workers, market vendors, and other citizens living in designated COVID-19 “red zones.”

The share of people vaccinated in the 10 nations of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. (Source: Our World In Data)

But none of this was connected directly with the country’s vaccine distribution, a metric on which it has managed to outpace not just its peers in Southeast Asia, but also many of the world’s wealthiest nations, including the United States. Last month, Mekong Strategic Partners, a Phnom Penh-based investment and advisory firm, published a report claiming that the country is “on track to complete its program around eight months ahead of schedule.”

At current rates, the report stated, the country will reach a full vaccination rate of 70 percent on September 21, compared to March 22 for the Philippines, July 22, 2022 for Indonesia and Thailand, and September 22 next year for Vietnam. Meanwhile, Phnom Penh ranks as one of the most vaccinated capital cities in the world, with around 99 percent of its adult population fully inoculated. According to the report, this puts the country in a good position to end lockdowns and reactivate its stalled economy sooner than many other nations.

What explains the success of Cambodia’s vaccine distribution campaign? Obviously, the country’s contained geography and relatively small population of 16.5 million have helped. But the report also credits the government’s “clear and simple ring-fenced distribution plan based on location, rather than more complicated age-tiering,” and its introduction of vaccine mandates for large sections of the community, including the armed forces and civil servants. The government’s efforts have also been aided by low levels of vaccine hesitancy compared to many other nations.

Crucially important, too, has been Cambodia’s effective procurement of enough vaccines to cover its population. According to the report from Mekong Strategic Partners, the country has acquired vaccines “by any means possible,” including donations via the global COVAX facility, as well as bilateral donations and direct purchases from a number of countries.

But by far the majority of these – around 27 million of the 30 million doses received so far – have come from China, the government’s chief patron and partner. While it is true that the inactivated vaccines produced by Sinopharm and Sinovac Biotech are less effective than the mRNA vaccines produced by Pfizer and Moderna, the Chinese-made vaccines have helped reduce hospitalizations and death rates in Cambodia, even as the Delta variant of COVID-19 continues to circulate among the country’s population.

Cambodia’s vaccine procurement strategy reflects the intimate relationship that has developed between Hun Sen and the Chinese government over the past two decades. As Beijing government has poured in money to build vital infrastructure, it has weaned his Cambodian People’s Party government off Western development aid and thus freed it from the good governance and human rights conditionalities often attached to Western support.

While many in Washington will no doubt give Cambodia’s vaccination a reflexively negative spin – as a further sign of the government’s policy of obeisance to Beijing – it’s hard to argue that the government had any realistic alternative. With Western nations hoarding doses for their own populations, spurning Chinese vaccines would have been irresponsible for a nation in Cambodia’s position.

In this sense, it demonstrates one of the shortcomings of the U.S. strategy in Southeast Asia, which has focused heavily the negative impacts of China’s influence in the region, while presenting a sanitized vision of the U.S.-led “rules-based international order” that Beijing is allegedly seeking to supplant. But in a context of rampant COVID-19 outbreaks and the associated economic privation, the region is likely to be less impressed by what the U.S. says than what it actually delivers.

An earlier version of this article described the COVAX facility as an initiative of the World Health Organization (WHO). In fact, COVAX is co-led by Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the WHO, and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI).