In early August, Sooma was carrying on with her work as an assistant in the crimes division of the Herat City Police Department. She still had little reason to believe that fighting on the outskirts of town would arrive at her doorstep. She reported to work every day and her earnings went to support her five children, whom she had been forced to raise on her own after the death of her husband, a policeman, in the conflict three years earlier.

Sooma’s world was upended when Herat’s defenses crumbled on August 13 and the Taliban drove into town, seizing government offices and the police station. One fighter began to threaten her, she explained in an interview. “He threatened to rape me and kill my children if I would not marry him,” she said, her voice trembling. “He persisted and I had no choice in the matter. He forced me to marry in September with a mullah’s consent.”

Since that day, Sooma, who asked that she be identified by a pseudonym to protect her identity, says her life has been a nightmare. “It is like he is raping me every night,” she said. “I am in a bad way and I want to kill myself, and I would do this except for my duty to raise and protect my children.”

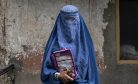

Intense hardship, including violence, has long been a lived reality for Afghan women. In 2018, some 80 percent of all Afghan suicides involved women taking their own lives, often when they see no way out of a domestic struggle. U.N. reports consistently reflect roughly 80 percent of Afghan women reporting domestic abuse at the hands of men.

In recent years, however, Herat had become a relative exception to the standard harshness of daily life for most Afghan women.

The city, lined with fruit orchards and grape trellises, has long been known to Afghans as a cradle of culture. Over the past two decades it had evolved into a center for open expression with a thriving literary scene where single young women and men could sit together over tea in public spaces and be heard reading their own poetry aloud to one another.

All that changed on August 13 when the Taliban came to town. Most women and girls retreated to their homes, but dozens of the city’s bravest women dared to protest against the Taliban’s banning of girls’ education and imposition of restrictions on their movement. Women marching in the street said they wanted to “be able to continue going to their jobs without requiring a mahram (male family member as a chaperone); and to have girls above grade six return to school,” according to a detailed September Human Rights Watch report focused on Herat.

Those voices were soon stifled. On September 7, Taliban fighters beat protesters with rubber straps and fired weapons indiscriminately, killing civilians before banning protests outright.

“Several of the single women we spoke to in Herat felt that the only way to survive the new era would be to get married in order to move around the city,” said Heather Barr, co-director of the Women’s Rights Division at Human Rights Watch.

Now, the Taliban, by preventing women from working and stopping girls in grades 7-12 from going back to school, are setting the ideal conditions for violence against women, said Barr, who is based in Islamabad, Pakistan.

She said that Human Rights Watch is also trying to monitor the phenomenon of forced marriage since the Taliban came to power, but has not been able to gather enough evidence to date to say that the Taliban are condoning the practice at the leadership level.

The Taliban have argued in the past that “arranging marriages” for widows like Sooma is for the good of society and the children living with single mothers.

Domestic violence in Afghanistan is brought on by decades of incessant warfare, poverty, and a long-standing patriarchal culture. In a country whose total population is approaching 40 million, there are at estimated 2-3 million widows. Until recently, the former government was paying some 100,000 Afghan widows the equivalent of $100 a month in a government stipend to live on. This has also ended, however, with the Taliban seizure of power. In conservative, mostly Pashtun regions of the country, a widowed Afghan woman is often given in an arranged marriage to the brother or close relative of her deceased husband, a move seen by the patriarchal culture as protecting the “honor” of both the widow and the family, even if the brother is already married.

What is most disturbing to Afghan women and international human rights advocates, however, is mounting anecdotal evidence that the Taliban is allowing its own fighters to use threats of violence to interpret already harsh traditional terms of marriage to satisfy their own personal desires.

A Taliban spokesman, Zabiullah Mujahid, has denied allegations that the Taliban were or are forcing women into marriage, insisting that such actions would violate rules of Islam. In January 2021, the Taliban’s enigmatic leader and former Sharia judge Haibatullah Akhundzada issued a statement urging the group’s commanders to forgo taking multiple wives, a phenomenon that has been widespread among the group’s well-heeled leadership, whose activities the group funds. Though Muslim men are permitted by religion to have up to four wives if they can treat them equally, the communique said the practice was inviting “criticism from our enemies.”

Yet the pronouncements and denials from the Taliban present a clear case of orders to “do what we say, not what we do.” Almost all of the Taliban’s senior leaders have already taken multiple wives. Indeed, the movement’s founder, Mullah Mohammad Omar, and his successor, Mullah Mansoor, both had three wives. By comparison, Haibatullah is believed to have only two; however, the Taliban’s new deputy head of state, Mullah Abdul Baradar has three wives and he wed his last while under Pakistani house arrest.

Afghan women’s rights activists say that the Taliban’s fresh denials of abuse are a cover-up for what is taking place out of sight. “The Taliban has changed but not in a good way,” said Atefa Kakar, a former U.N. employee now living in Germany, pursuing a master’s degree and advocating for Afghan women. “The Taliban still has an extremist and highly misogynistic ideology even though it is trying to fool the world with denials. Afghan women don’t believe the Taliban even as they face a reality of growing powerlessness.”

“As far as the international community and what they can do to help,” she continued, “we feel we have already been abandoned. Personally, I do not see the international community – including the United Nations – being able to persuade the Taliban to change their ways or institute a humane policy either on the marriage or education front.”

Even after the Taliban seized major Afghan cities like Herat, the U.N.’s chief of human rights, Michelle Bachelet, insisted that the rights of Afghan women and girls would be a U.N. priority. Specifically, Bachelet said, “a fundamental red line will be the Taliban’s treatment of women and girls, and respect for their rights to liberty, freedom of movement, education, self-expression and employment, guided by international human rights norms. In particular, ensuring access to quality secondary education for girls will be an essential indicator of commitment to human rights.” Her insistence on a “red line” was similar to statements coming out of the U.S. State Department prior to the Taliban takeover.

But even as the U.N. and the Security Council have insisted that the Taliban must rise above their current education goals and treatment of women, the group’s leadership has not said if it will allow girls above sixth grade to reenter school, noted Barr.

In addition, Afghan women are making clear what they think of the Taliban’s promises. Afghan women working with the U.N. in Afghanistan, many of whom helped monitor human rights and political affairs, are trying to leave the country and, in some cases, have already left.

“I have heard from my own former colleagues still working in the U.N. – women who would have never considered leaving Afghanistan because they have a good job and salary – that they are trying to escape the country now out of fear that their teenage daughters will be forced into marriage with a Taliban fighter,” said Kakar, who previously worked for both the political mission, UNAMA, as well as for the group U.N. Women. “I think that wanting desperately to leave an excellent job for an unknown country tells you all you need to know about the state of fear gripping Afghanistan at the moment due to the Taliban’s takeover.”

Family fears are driving migration across regional borders. Since the Taliban takeover, members of the embattled Afghan Hazara minority, which embraces Shia Islam and is disdained by the Taliban leadership, have fled in the thousands to both Pakistan and Iran, though crossing the fenced border is fraught with extreme danger. One man who fled Afghanistan with two young sisters told Deutsche Welle that he had left because he did not want his sisters married off to Taliban fighters.

Close to the Pakistani border but inside Afghanistan, Shabnam, a high school student, who asked to have only her first name in this story, said that she also had been forced into an unwanted marriage. A Taliban loyalist in Parwan province had tormented her, she said, insisting that if his group came to power, she would have to surrender her virginity to them.

When the Taliban took the district where she lives, she says, “the same boy who taunted me just claimed me as his wife and was given permission” by the Taliban local leaders to do so.