At the 26th Conference of Parties (COP26), Prime Minister Narendra Modi committed India to a net-zero carbon emissions target by 2070. In essence, net-zero implies the employment of mechanisms that would offset the amount of carbon emitted by a country into the atmosphere by absorbing an equivalent amount of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere.

The net-zero commitment is part of a strategy of Panchamrit or “five elixirs.” Four out of five of these so-called elixirs are short-term goals that would pave the way for achieving a net-zero emissions target by 2070. The immediate goals are:

- Reaching a non-fossil fuel energy capacity of 500 GW by 2030;

- Fulfilling 50 percent energy requirements via renewable energy by 2030;

- Reducing CO2 emissions by 1 million tons by 2030; and

- Reducing carbon intensity below 45 percent by 2030.

In contrast to this net-zero commitment, in the final days of COP26, India objected to the provision referring to a phasing out of fossil fuel subsidies and coal in the final draft of what is now the Glasgow Climate Pact. Supported by a few other developing countries, including China, Iran, and Cuba, India floated an amendment to use the phrase “phase down” instead of “phase out” coal power. Emphasizing the argument that each country will reach net-zero as per its particular context, India’s Environment Minister stated: “Developing countries have a right to their fair share of the global carbon budget and are entitled to the responsible use of fossil fuels within this scope… Developing countries still have to deal with their development agendas and poverty eradication. Towards this end, subsidies provide much needed social security and support.”

The commitment to net-zero and the last-minute objection to phasing out of coal reflects India’s mixed strategy at international climate policy negotiations. The strategy is grounded in the country’s traditional support for differentiated responsibilities, but outlined by a more flexible approach to emissions reduction. In this context, this article analyses how India’s commitment to reaching net-zero emissions by 2070 fits within the country’s current climate action policies.

Achieving Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs): Strengths and Weaknesses

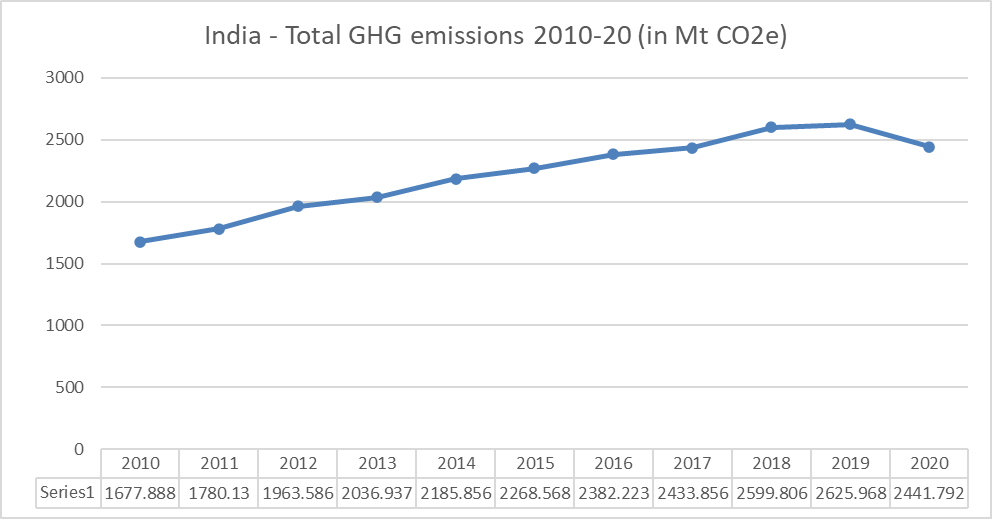

As per the Global Carbon Project, India’s total emissions were 2,442 million tons of CO2 equivalent (MtCO2e), making it the third-largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emitter in the world after China (10,668 MtCO2e) and the United States (4,713 MtCO2e). While India’s total emissions are nowhere near that of the top two countries, emissions have increased steadily over the last decade as seen in Figure 1. The slight dip in 2020 could arguably be due to the pandemic and a prolonged economic slowdown.

Source: Global Carbon Project 2020

Behind the steady rise of India’s total emissions is a big focus on developmental priorities over the last two decades. India seeks rapid growth through 2030 for a projected population of about 1.5 billion, with 40 percent living in urban areas. This approach incorporates priorities such as poverty eradication, education, Make in India, infrastructure development and electricity, housing, and health for all, to name a few. However, developmental aspirations inevitably result in a net increase in emissions. These emissions are supposed to be offset by the following key comprehensive and balanced NDCs:

- To reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33-35 percent by 2030 from the 2005 level;

- To achieve 40 percent of electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel by 2030;

- To create an additional carbon sink of 2.5-3 billion tons of CO2 equivalent by 2030

As of 2020, India was well on its way towards meeting its NDCs. According to India’s 3rd Biennial Update to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), it was able to reduce its GDP emissions intensity by 24 percent during 2005-16. The country’s per capita emissions also remain low at 1.94 tCO2 per capita, less than half the global average of 4.2 tCO2 per capita. Renewable energy — solar, wind, and biomass power — accounted for over 24 percent of India’s total installed electricity capacity as of July 2020. Factoring in large hydropower projects and nuclear, India’s non-fossil fuels totaled 38 percent of the country’s installed capacity, which is almost as much as its NDC under the Paris Agreement. However, the country’s forest and tree cover has increased by only 5,188 km2, yielding a 42.6 million ton (Mt) carbon sink increase against a commitment of 680-817 Mt increase.

A flipside to India’s achievement so far is that the NDCs themselves are not ambitious enough. The global Climate Action Tracker (CAT) rates India’s 40 percent non-fossil fuel electricity capacity target as “critically insufficient” and its emissions intensity target as “highly insufficient.” This review leaves much scope for improvement if it is to be consistent with the 1.5 degrees Celsius global warming limit under the Paris Agreement.

Nevertheless, the updated targets post COP26 will revise the current timeline and require bold measures if India seeks to maintain the momentum it has had. Simultaneously, the government might need to reconsider some recent policy measures that are counterintuitive to its renewed commitments. Much ambiguity still exists around various aspects of the targets Modi announced at COP26. Moreover, the path toward achieving these targets is yet to be revealed. Nevertheless, there are some identifiable strengths and weaknesses.

Let’s look at the twin commitments of reaching non-fossil energy capacity of 500 GW and fulfilling 50 percent energy requirements via renewable energy by 2030. In July 2021, the installed capacity of renewables in India was 98.8 GW. While this is a significant increase from a lowly 39 GW in 2015, it is still a long way from the commitment of 175 GW by 2022 under the sustainable development goals (SDGs). Even so, CAT projections show that India will most likely reach its targeted non-fossil fuel capacity. If the projections are true, they would most likely come on the back of cheap solar and wind power since the two have the lowest cost among electricity sources in India, increasing investment in solar photovoltaics, incentive-driven manufacturing hubs for renewables, and a new policy push towards Biofuels.

However, the commitment toward renewables has been juxtaposed with increased investment in the extraction of fossil fuels, mining infrastructure, and transportation to increase coal production to 1 billion tons by 2023-24. Coal-powered electricity generation has increased at an annual rate of 6 percent since 2015, with the coal capacity expected to grow from 202 GW in 2021 to 266 GW in 2030. This is evident from the recent opening up of 40 new coal mines for auction. This renewed push toward coal explains India’s last-minute objection to the “phasing out” of coal at COP26.

Other recent decisions of concern that could weaken the updated commitments include the government’s investment in palm oil. The National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm proposed to cover an additional area of 6.5 lakh hectares (lha) under oil palm cultivation by 2025-26 and another 6.7 lha by 2029-30. Production of crude palm oil is expected to go up to 1.12 million tons (mt) by FY2026 and up to 2.8 mt by FY2030. Notably, edible oil plantations tend to replace natural tropical forests, thereby depleting biodiversity and affecting natural carbon sinks. Additionally, they may deplete groundwater levels, increase deforestation, and lead to habitat loss for native creatures.

Glasgow and Beyond: Negotiating an Uncertain future

There is an identifiable discrepancy between India’s renewed climate commitments and its domestic policies toward climate action. This discrepancy mirrors the state of affairs at the global level: While the Paris Agreement seeks to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius, an ambitious target that the G-20 countries agreed on in their October 2021 summit in Rome, current NDCs and net-zero targets set by countries would fail to achieve it. CAT projections show that current policies would be able to limit warming to 2.7 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Even in the most optimistic — albeit highly unlikely — scenario, the world would be 1.8 degrees Celsius warmer by the end of the century.

While most countries are willing to set ambitious targets at multilateral fora such as the COP, real-world action is a far cry from what it needs to be. Some experts have even criticized the concept of net-zero as a “recklessly cavalier burn now, pay later approach,” which is over-reliant on incremental cuts to fossil fuel consumption and carbon dioxide removal techniques. Net-zero can indeed distract from the urgent need for deep emissions reductions if 2030 targets and short-term action are inconsistent with steps towards their achievement, thereby allowing governments to hide behind aspirational net-zero targets. This is evident in the fact that the 10 hottest years on record have all come in the last 25 years, during a time when global consensus on climate action has seen its most important milestones in the form of the Kyoto protocol, Bali Action Plan, Copenhagen Accord, and the Paris Agreement.

The above discussion becomes even more critical as the global economy recovers from the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. As per projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA), post-pandemic recovery could cause a 4.8 percent growth in carbon emissions in 2021, leading to the single-largest increase in emissions since the economic recovery from the global financial crisis of 2008-09.

For India, the projections show that economic recovery would increase emissions by 1.4 percent compared to pre-pandemic levels, driven by higher coal demand. This would make short-term deeper emissions cuts even more justifiably unfair and impractical for India. It is so because deeper cuts rely on costly and energy-intensive direct carbon capture technologies. Deployment of such technologies by developing countries requires fulfilment of climate finance and technology transfer obligations on part of the developed world. The latter, however, appears largely unwilling to fulfil these obligations. For instance, while developed countries had pledged to raise $100 billion every year by 2020 to aid mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing countries, this 12-year-old goal has not been achieved yet, something that the Glasgow Pact “notes with deep regret.”

To conclude, India’s net-zero target and updated NDCs are certainly aspirational, keeping in mind its development needs during the post-COVID recovery. However, they fit a general pattern of incremental progress on climate action at the global level that lacks the collective sense of urgency required to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius below pre-industrial levels. How far India and the world can go with limited short-term emissions reduction and ambitious long-term climate action plans is something that remains to be seen.