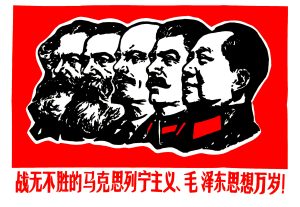

The geopolitical discourse of our times is dominated by a growing multipolarity, unlike 30 years back, when the world was dominated by two superpowers: The United States and the erstwhile USSR. In fact, the world has witnessed a massive geopolitical metamorphosis in the first half of the 20th century, as once-great kingdoms, such as the Russian, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian, British, and French empires have transformed into modern democracies, socialist republics, and communist dictatorships. This metamorphosis is ongoing, and is particularly evident and noteworthy in the case of China.

The rather unexpected emergence of People’s Republic of China (PRC) as a near-superpower in the past decade-and-a-half was met by denial by the U.S. foreign policy apparatus until relatively recently. Whatever their party, successive U.S. administrations downplayed China’s growing strategic and military strength until the election of President Donald Trump in 2016.

The harsh and belated realization of China’s economic and military strength has at least partly contributed to the withdrawal of the U.S. armed forces from Afghanistan and Iraq, and the reallocation of more resources to the Indo-Pacific to counter China’s aggressive behavior. Many analysts attribute China’s sudden rise to its strong export-led economic growth and Xi Jinping’s assertive leadership. However, one crucial factor responsible for China’s growing strategic hegemony that is rarely discussed is its unparalleled commitment and rigor to learn from the USSR’s mistakes.

The PRC and its leaders have taken strong note of the strategic mistakes that ultimately led to the disintegration of the Soviet Union three decades ago this month. These mistakes can be classified into three broad categories.

Tolerance of Liberal Values Among the Citizenry

During the mid-1980s, Mikhail Gorbachev, then general secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and later president of the USSR, advocated for opening of the Russian economy to globalization and a managed liberalization of the country’s politics, policies that came to be known, respectively, as glasnost and perestroika.

These policies led to sudden exposure of the Russian people (many of whom were confined to socialist ideas of living) to Western consumer lifestyles, civil liberties, and freedom of thought and expression. The liberalization of the USSR was also interpreted as a sign of weakness by some segments of the population, creating fertile grounds for political unrest and ethnonationalism and a sense of hostility towards the centralized communist system of governance.

China, on the other hand, has been very stringent in controlling the dissemination of information and restraining free speech on both digital and non-digital platforms. Hence, it is no surprise that China even today does not allow Facebook to operate in its digital territory, given that the leadership views it as an uncontrolled tool of free speech and expression.

The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has also enabled the famous “Great Firewall of China,” which aims to maintain a steady surveillance on the entire Chinese internet. The system of Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) enables CCP intelligence agencies to read and censor private emails, messages, and any other form of digital communication. The CCP’s recent private data policy of is also another important step in this particular direction.

Disastrous State-Led Economic Policies

As the Cold War entered its final phase, the USSR’s socialist economic model came to the verge of collapse due to the high costs imposed by proxy wars, fluctuations in the prices of oil and natural gas, and limited avenues for increasing government tax revenues. The dire economic situation also contributed to the popular resentment towards the socialist economic development model and its various privations.

China, on the other hand, after its earlier hiccups in the form of the disastrous Great Leap Forward in the 1950s, transitioned to a higher economic growth path by adopting a coherent strategy of “state-controlled capitalism.” The economic reforms introduced by Deng Xiaoping in the late 1970s laid a strong foundation and ultimately led to China’s accession in 2001 to the World Trade Organization as a “non-market economy.” Learning from the economic blunders of USSR, China rather used its WTO entry to become the world’s factory of consumer goods by using dumping practices, providing relentless state support that helped its domestic companies set up giant manufacturing bases, implementing price controls, and maintaining a deliberately weak intellectual property regime.

Unlike the USSR, China hid its true geopolitical ambitions in order to gain strategic favors and concessions from different countries, especially the U.S. and the European nations. The close coupling of the Chinese economy with those of other countries and its strong domestic market have frustrated any coordinated global effort to contain Chinese geopolitical ambitions today. China is furthering its strength in semi-conductors, computer chips, rare earth elements, quantum computing, and artificial intelligence, in order to maintain its strategic position vis-à-vis the United States.

Involvement in Proxy Conflicts

Proxy wars were used as a strategic tool both by the U.S. and USSR to disseminate their ideologies globally. These proxy wars were fought in almost every geographical region. The U.S., as a highly industrialized and capitalist economy, was able to sustain the economic costs of these proxy wars unlike the USSR, whose economy strained under the need to maintain a competitive military.

Since its short war with Vietnam in 1979, China has not been involved in any proxy warfare that requires a substantial investment of resources. Taking a cue from the USSR’s mistakes, China has gradually developed tools and mechanisms to undertake unconventional or hybrid warfare in the form of cyber attacks and information warfare, which are often difficult to prove in terms of their origin. The strategy of building artificial islands has been particularly proved helpful in advancing the expansive Chinese claims over the South China sea.

In a nutshell, learning from the mistakes of USSR during the Cold War, China has very tactically camouflaged its fault lines, whether they be in Xinjiang, Tibet, Hong Kong, or Taiwan, in pursuit of its broader strategic goals. Hence, it would be prudent for other countries, especially China’s neighbors and concerned outside countries like the U.S., to take note of China’s strong ability to adapt itself based on the mistakes of other socialist and communist republics. These realizations may also greatly help these countries craft an effective strategic response to China’s assertive behavior.