Vietnam’s pledge at the U.N. Climate Change Conference in Glasgow (COP26) to achieve net zero carbon emissions by 2050 was a bold move. Vietnam also added its name to declarations on ending deforestation and reducing methane emissions.

These are lofty ambitions, a potential model for developing countries in Asia and across the world, but for middle-income countries like Vietnam climate change mitigation cannot come at the expense economic development and improving the lives of the poor.

Vietnam is not short of reasons to be concerned about climate change. With 70 percent of the population living along the coast or in the country’s two major deltas, it is at risk from sea level rise, floods, drought, and other extreme weather events. Thousands have already been relocated from vulnerable regions, and increased saltwater intrusion, typhoons, flooding, and landslides could force hundreds of thousands more from homes and farms.

The bitter reality of climate change is that the people and communities that will bear the heaviest burden did not cause the crisis. According to UNCTAD, the richest 1 percent of the world’s population generated more than twice the emissions of the bottom 50 percent from 1990 to 2015.

As Vietnam’s Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh noted in his remarks at COP26, it is imperative that we ensure equity and justice in our response to climate change. Climate justice demands that advanced countries take the lead in climate change response and share the cost of mitigation and adaptation, and that the most vulnerable communities in all countries are protected from its adverse material and economic effects.

For example, a recent UNDP study in Vietnam found that 110,000 households across 28 coastal provinces are vulnerable to the increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events as their shelters have not been constructed to withstand climate-induced typhoons and historic floods. Vietnam’s international partners could make a difference with financial and technical help to develop resilient infrastructure and housing in these locations.

Vietnam’s latest power development plans still rely heavily on the construction of new coal-fired power plants because of limits on hydro-electric power and domestic natural gas supplies. These plans are now being reconsidered to align with the government’s COP26 commitments. There are hard choices to make, but with an eye to future health and prosperity of the nation, they are an opportunity to change course.

Achieving net zero emissions by 2050 cannot come at the expense of economic growth and poverty reduction. Vietnam has made tremendous strides toward eliminating energy poverty even in rural and remote areas. As of 2020, only 5 percent of households consumed less than 30kwh of electricity per month, a standard benchmark for energy poverty. Near-universal access to electricity and reduced dependence on hazardous and polluting fuels have improved the lives of millions.

Access to energy at a reasonable cost has also been key to Vietnam’s successful economic development for three decades. Development of essential infrastructure requires energy-intensive industries like steel and cement. Fertilizer production helps increase farm productivity, rural incomes, and domestic food supply.

If Vietnam is to meet the energy needs of the economy and its COP26 climate commitments, it will need to significantly expand the development of renewable energy sources and rapidly reform energy governance.

Climate finance remains a major stumbling block for developing countries. In 2009 developed countries promised at least $100 billion a year to support the developing world in reducing emissions and adapting to climate change by 2020, a target that was not met. A recent report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) concludes that in 2019 only about $80 billion in climate finance was provided.

Even $100 billion would be a drop in the bucket compared to the finance required to meet 2030 climate targets. The Climate Policy Initiative estimates that annual investment needs to rise five-fold to meet the need for climate action by 2030, to keep average temperature rise to well below 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial times, in line with the Paris Climate Agreement.

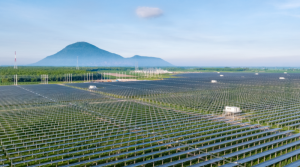

Ultimately, countries like Vietnam will rely mostly on domestic sources for climate finance. Vietnam enjoyed a solar power boom adding 10 GW of capacity from 2018 to 2020 in response to generous feed in tariffs, a tax holiday on solar investments, and other incentives. Domestic banks were the main source of finance, investing $3.6 billion during this period. Off-shore wind power has even greater long-term potential for this coastal, densely populated country.

Further penetration of renewal energy depends on modernization of the grid, development of micro regional grids and electricity storage, which the government estimates will cost $33 billion over 10 years, and structural reforms to introduce competition and adjust pricing to supply and demand conditions.

Vietnam’s track record of reducing energy poverty and transitioning to renewable energy sources shows that climate leadership does not have to mean giving up on inclusivity and higher living standards. The road ahead will not be easy, but with international support and a commitment to domestic reform, Vietnam could become a model for middle-income countries seeking just climate transitions in the post COP26 era.