Since February 24, the Russian invasion of Ukraine had dominated world politics and the social media sphere alike. As Vietnam assumes a principled neutrality on the conflict between its post-Soviet brothers, divisive conversations are taking place among the country’s online public.

For Vietnam, the timing of the conflict could not be more awkward: it comes three months after Hanoi and Moscow celebrated the 20th anniversary of their comprehensive strategic partnership and barely two weeks after the 30th anniversary of Vietnam’s relations with Ukraine. Caught off guard by Russia’s sudden aggression against one of its comprehensive partners, Vietnam finds itself in a diplomatic bind.

Echoing the minimalist response of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Vietnam has responded euphemistically with expressions of “deep concern” and calls for “peaceful solutions” to the armed conflict, without naming any countries. Given Vietnam’s friendly relationships with the parties involved – particularly Russia, its largest arms supplier – such a tepid response perhaps comes as no surprise. The country responded similarly to Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014, quietly acceding to, and later affirming, the controversial referendum that followed.

This time, however, a quiet apprehension simmers in Vietnam as Russia intensifies its attacks against Ukraine. The dramatic changes this month have made Vietnam reverse its perceptions of “business as usual” and the notion that it need not evacuate its citizens in Ukraine

Nonetheless, Vietnam’s current attitude appears to be one of principled neutrality, as the Vietnamese ambassador to the United Nations reaffirmed the country’s support for international law and respect for national sovereignty. Yet despite evocative references to Vietnam’s own war-torn history and its criticism of great powers’ hegemonic ambitions, Vietnam abstained in the March 2 U.N. General Assembly resolution that “deplored” the Russian aggression against Ukraine.

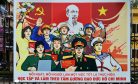

Domestically, the Vietnamese have a historical affinity for Russia and its people. This originates in the Soviet Union’s precious support for Vietnam in the 1970s and 1980s. When the socialist bloc still existed, being sent to the Soviet Union for education was considered a great honor. Generations of Soviet-educated cadres, officers, and scientists still fill Vietnamese academic and political institutions. Just as Vietnamese officials continue to pay respects to the Lenin statue gifted by the Soviet Union to Hanoi, the Vietnamese press derided the toppling of the Russian-backed Ukrainian leader, Viktor Yanukovych, in 2013. A Gallup International Poll in 2017 on perceptions of Global Leaders found that Vietnamese are more favorable of Putin than Russians, with 89 percent approving his leadership.

This time, however, absent an opinionated stance by the state, opinions in the Vietnamese press appear uncharacteristically mixed. The press has largely deviated from its typically pro-Russia coverage and provided detailed, if largely neutral, accounts of the conflict. This shift appears to have started when Russia began its invasion of Ukraine. Coverage of NATO expansionism and the Western role in escalating the conflict has decreased since the invasion occurred.

The press coverage now centers on other aspects of the conflict in Ukraine, while avoiding framing it as “an invasion.” Some emphasize the economic ramifications for Vietnam, especially rising oil prices, and draw lessons from Russia’s and Ukraine’s miscalculations for a restrained and neutral solution to the conflict. Others provide a humanitarian outlook by publishing images of overseas Vietnamese huddled in bunkers and the perspective of the Ukrainian chargé d’affaires in Vietnam. Some military-affiliated sites amplify Russian news and propaganda, while some mainstream and diplomatic sites are subtly critical of Russian aggression.

These divides are clearer among Vietnamese public opinion, as expressed online. On Facebook, Vietnam’s most popular social media network, there is support for Putin’s actions, which blames Ukraine for poking the hornet’s nest, as much as criticisms on humanitarian grounds and comparisons to Vietnam’s relationship with China. These differences likely emanate from Vietnam’s partial censorship of the internet and differentiated access to international news sources. For example, the Vietnamese site of Russia-affiliated Sputnik is accessible in Vietnam, while the Vietnamese BBC is not.

Pro-regime opinions defend the state’s stance as “bamboo diplomacy” against calls to criticize Russia and side with Ukraine. These intertwine with pro-Putin opinions that draw heavily from Soviet-Vietnam nostalgia with a vulgar realism that chalks Putin’s actions up to a self-explanatory “national interest.” The most popular responses are from tabloid-like sites that regularly make fun of the Ukrainian “comedian” president, glorify Putin’s strongman personality, and exaggerate Western ignorance and negligence.

These opinions are nonetheless met with similarly viral responses that criticize their “Putin-mania.” These responses emphasize Putin’s brutality, show solidarity with Ukraine, decry the inhumanity and illegality of the conflict, and call out the shallow politics of Putin admirers in Vietnam. Unlike the sensationalist and populist character of the former set of opinions, these opinions are generally made by political-savvy individuals, educated youths, and artists with greater exposure to international news and information.

One thing unites these public opinions and the state: The idea of “independence,” an animating yet open-ended concept in the Vietnamese psyche. Critics of the war attach the concept to ASEAN’s non-interference principle, respect of sovereignty, and the precedent it sets for Chinese aggression, while supporters refer to Vietnam’s “four no’s” principle, “national interest,” “bamboo diplomacy,” and American hypocrisy. These talking points proliferate as the conflict rages on, with each new statement by the Vietnamese state voraciously shared and reinterpreted by supporters and detractors alike.

Current Vietnamese Prime Minister Pham Minh Chinh, speaking during Vietnam’s 31st Diplomatic Conference last year, summarized the country’s current diplomatic approach thus: “We do not choose sides, but choose the right cause of our time.” Yet as the international community swings further toward support for Ukraine, Vietnam may grapple even more with the exact nature of its “right cause.” Vietnamese neutrality, principled though it may be, is being tested as its citizens and neighbors ponder corrosive effects of Russia’s actions upon its long-cherished principles of sovereignty and international law.