The loss and leakage of U.S. equipment due to poor oversight and accountability of weapons strengthened the Taliban’s forces. The U.S. delivered a significant amount of security assistance to Afghanistan since 2002 — for nearly 20 years before the Taliban’s takeover in August 2021. The large quantity of weapons, ammunition and equipment provided to the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) has had unintended and negative impacts for the security and humanitarian situation in Afghanistan, as well as toward achieving U.S. policy goals. The scale of such shortcomings is likely to have long-term security implications in the region.

Security Assistance Poses a Dilemma for the U.S.

In 2020, U.S. military aid amounting to $16.22 billion was supplied to 143 recipients globally. Security assistance is a global systemic risk, as the majority of illicit weapons were at one point diverted from legal channels. Not only do the proliferation risks seen in Afghanistan raise doubts regarding the effectiveness of the billions of dollars of U.S. security assistance distributed globally, but it also puts in question the policy of supplying weapons to government-backed forces in conflict-affected countries. Security assistance and weapons supplied to Ukraine could similarly lead to unintended consequences of arms proliferation to Russian forces, and beyond Ukraine’s borders in years to come.

This is a dilemma for the United States. To prevent unintended outcomes, one option would be to only arm forces if leakage can be prevented with certainty – yet in situations of conflict and insurgency this prospect can be especially difficult. The U.S. allies that need weapons and equipment in the first place typically lack the capacity and ability to control such weapons, putting into question the logic behind security assistance.

If the U.S. continues to follow a policy of arming parties in conflict (either directly or indirectly) as a staple of its foreign policy and counterterrorism strategies without putting in place comprehensive measures to prevent diversion, it will continue to undermine U.S. security interests by aiding the parties it opposes.

Weapon Supplies to Afghanistan

Nearly a year ago, the swift takeover of Kabul by the Taliban marked a new period for the conflict in Afghanistan and the end of the long-standing U.S.-backed government. The events of August 2021 were covered largely in the media as a disaster for U.S. policy and the humanitarian situation as the Taliban ramped up attacks against Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) and urban areas. Yet we do not give enough attention to the systemic and underlying issue of weapons diversion taking place for over a decade prior. The fact that the U.S. has historically failed to secure the weapons and equipment supplied by the U.S. and NATO allies is overlooked as one of the contributing factors of the Taliban’s strength, sophistication, and capacity to sustain armed conflict leading to the events of 2021.

Estimates of U.S. spending between 2002-2008 indicate about $120 million spent on 242,000 small arms and light weapons (SALW) to the ANDSF, including a variety of rifles, pistols, machine guns, mortars, and grenade launchers. According to a 2016 estimate, the Pentagon accounted for less than 48 percent of total SALW supplied. The scale of oversights on weapons accountability created vulnerabilities to displacement, loss, and theft by the Taliban and other armed actors – for example, a recent report by Conflict Armament Research documented U.S.-manufactured M4 and M16 rifles recovered by the ANDSF from the Taliban and other armed groups, some of which were confirmed to be supplied to the Afghan National Army (ANA), and likely originating in ANA stockpiles.

The Taliban have also notoriously used U.S. night vision goggles in attacks on Afghan forces at night, employed armored Humvees as SVBIEDs in complex attacks, and featured U.S. weapons in propaganda footage. By the time Kabul fell, the Taliban had already been in a position to capture territory.

Large amounts of U.S. supplied weapons were left behind in Afghanistan – many of these could continue circulating throughout the region via black market exchanges or other means of diversion for years to come. The question of “who now has, or will soon have, access to” the unaccountable quantities of U.S.-supplied weapons presents serious challenges for security in Afghanistan and beyond. The consequences of poor accountability of weapons and ammunition is unfortunately a common story in this context and others, such as Iraq, and should encourage critical reflections on U.S. foreign policy decisions. The U.S. would be amiss if it overlooked the elephant in the room: the policy of arming parties in conflict.

Systematic Issues in Weapons Accountability

As of December 31, 2020, the U.S. Congress had appropriated more than $88.3 billion in security assistance to supply and equip Afghan security forces with the goal to promote stability and security. Over the last decade at least 21 other countries have supplied the ANDSF with a total of $103 million in weapons, based on 2014 estimates. Donations of old stock and surplus ammunition by NATO countries, a practice strongly encouraged by the U.S., and through state-to-state gifts via U.S. holders helped to ensure the steady flow of weapons and ammunition over the years.

Systematic challenges and concerns over the large amounts of weapons transferred to Afghanistan have been documented by the Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) and the Government Accountability Office (GAO) repeatedly – citing lapses in accountability due to a lack of systematic recordkeeping, poor training, and a lack of clear guidance to Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) on the management of U.S. procured weapons throughout the supply chain (in storage and in transit).

While recordkeeping is required by the 2010 National Defense Authorization Act, GAO estimated in 2014 that over 50 percent of weapons intended for ANSF were not systematically tracked. Multiple databases and manual data entry practices made it nearly impossible to keep track of weapon losses accurately, particularly in light of capacity and technology gaps within logistics departments of the ANSF. When SIGAR compared the data in the two databases used, it found that of the 474,823 total serial numbers recorded in one database, 43 percent, or 203,888 weapons, had missing information and/or duplication. Moreover, 22,806 weapon serial numbers were repeated two or three times in the systems used, meaning that there were duplicate records of weapons shipped and received. Poor accountability also applies to ammunition, as demonstrated by an abundance of 7.62 x 39 mm ammunition in circulation in Afghanistan, which is a common U.S. military small arm caliber.

High corruption levels in the ANDSF further contributed to the misuse, loss, theft, and sale of weapons and ammunition, as demonstrated by some ANDSF personnel selling ammunition to locals, including the Taliban, and U.S. procured weapons appearing in black markets on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border. On top of this, high desertion rates contributed to weapon losses as well – an estimated 30 to 60 percent of Afghan soldiers deserted the army during or after their training, by the Pentagon’s own numbers, and U.S.-issued weapons have both been sold by soldiers and seized from abandoned check points.

Humanitarian Impacts of Weapons Proliferation

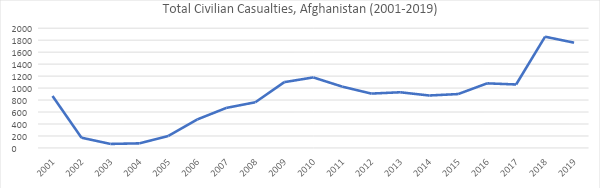

Arms proliferation is not only a strategic issue for the U.S. in Afghanistan, but it also imposes a heavy humanitarian cost. The increase in civilian causalities from 2003 onwards due to increased intensity of fighting has been fueled by the Taliban’s continued access to arms and ammunition (see Figure 1). According to Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), total civilian causalities in Afghanistan per year have increased between 2002 to 2019, and in particular in 2008 and 2009 and again in 2018. The Taliban primarily make use of small arms such as automatic rifles in attacks against civilians, but the group has also made use of suicide bombings and IEDs, particularly to attack civilian targets.

Figure 1

The Taliban used U.S. night vision goggles to increase attacks on Afghan forces at night (a trend which doubled following the capture of equipment from 2014 to 2017). There is also evidence that the Taliban seized weapons and an estimated 150 Humvees provided by the U.S. from abandoned bases and checkpoints, lending to the Taliban’s capacity to scale up the intensity of conflict. The deliberate targeting of civilians by the Taliban caused civilian casualties to nearly double, from 865 in 2017 to 1,688 in 2018 according to the U.N. Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA). When Kabul fell to the Taliban on August 15, 2021, more battle-related deaths had been recorded during 2021 than during all of 2020.

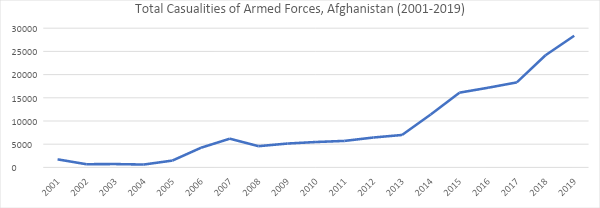

Figure 2