This is part two of a two-part investigation into the SSS’s increasing repression of Uzbekistan’s journalists. Part one is available here.

TASHKENT, UZBEKISTAN: An 11-week investigation into freedom of the press in Uzbekistan found that one of the biggest challenges journalists and bloggers face is pressure from the State Security Services (SSS). Journalists and bloggers say the SSS threatens and intimidates them and their families, and compels them to delete stories. The SSS demands that journalists and bloggers stop covering certain topics, such as high-level corruption within the government, the dealings of wealthy businessmen, religious practices, or anything vaguely disrespectful to the president or his family.

The investigation was blessed by the government of Uzbekistan which welcomed me as an American journalist and U.S. Fulbright Scholar — a research grant from the U.S. State Department — to research challenges journalists in this country face in reporting about corruption and government malfeasance. From March to June, I interviewed more than 40 journalists, bloggers, human rights activists, media watchers and government media monitors. I had previously interviewed nearly 100 journalists about obstacles to press freedoms in eight other post-Soviet countries.

Journalists in other post-Soviet countries face problems with intimidation, police overreach, court citations, fines, arrests and blocked websites. For example, in Belarus, the KGB openly films protesters and makes no secret of following journalists. But here, the SSS operates mostly in the shadows. Their threats and intimidations stifle journalists from reporting about corruption and problems that the newly elected president says he needs to know about to make reforms. The result is a media that is timid and self-censoring, a populace that is afraid to speak out, and a country that promotes the façade of a free press when in reality it is a country in the grip of propaganda.

Despite repeated requests, the SSS refused to meet with me in the course of reporting this story.

Rost 24 Threatened

Rost 24 editor, Anora Sodikova, announced on April 14 that she and her colleagues had been threatened with harm if she didn’t delete a story and video about Uzbekistan businessman Jakhongir Usmanov. His name came to Sodikova’s attention in the big data leak known as the Pandora Papers, which listed him as an owner of an offshore company, according to the story. Sodikova’s report also linked Usmanov to a charity fund that allegedly channeled large sums of money through this offshore account.

Sodikova refused to say publicly who was threatening her, even to Ezgulik, Uzbekistan’s only independent registered human rights organization, which is backing her. But she told me: It was the SSS who made the threats.

Anora Sodikova started her own media platform, Rost 24, a year-and-a-half ago after she was fired from a state-run news agency for posting a story on Facebook about residents’ reactions to a dam collapsing. Photo provided by the author.

“If I say it was the security forces, there will be a problem,” she said. “Besides, how can I prove it?”

At the same time Sodikova’s colleague received threatening phone calls, a “sniper blogger” began a smear campaign against her on social media alleging she was having an affair.

“This sniper blogger said the next time he would show pictures,” she said. “Just like they did with Feruza.”

Last year a female journalist from Qalampir.uz, Feruza Najmiddinova, was the target of a smear campaign when someone spread a video of a woman having sex with a man on a balcony. The anonymous poster said it was Najmiddinova having sex with a man who wasn’t her husband. Since then, Sodikova, a Muslim, has feared the SSS would use this tactic to ruin her reputation.

This was the third time the SSS had pressured Sodikova to take down a story. The first time she ignored the threats. The second time, in May 2020, an SSS officer called her husband, she said. That time she took down the article.

After the second SSS encounter, Sodikova’s husband separated from her for six months because he said he was afraid for their children’s safety.

“My husband said to me, ‘If you want to live with me, if you want to keep our family safe, if you love me and our children, you should give up your job.’ I told him I love my family and my friends. I can’t give up my job. I like my job also.”

She and her husband reunited in October 2020. Recently her oldest son Googled her name and asked: “Mom, are you really in danger?”

“I told him I’m okay.”

But later Sodikova learned that the Uzbekistan Creative Union for Journalists had gotten involved in her case.

“As the head of the union, I can’t skip this case,” said Olimjon Usarov, who until a year ago was the government spokesperson for the Uzbek Supreme Court. “I asked the prosecutor to investigate the case. To threaten a journalist is unlawful and criminal. If that person actually exists who threatened her, he will be found.”

Usarov said the police pulled phone records from her phone and her colleagues’ phones. They pulled surveillance videos near her home and office trying to find the man who came up to her in a restaurant and told her to take down her story. Police asked to speak with her husband.

“Anora asked us to take back the case,” Usarov said. “That was interesting for me.”

Sodikova did not welcome the union’s involvement. Instead, she worried that the government was trying to set her up. That is why she asked them to stop the investigation. She said she also fired her reporters at Rost 24 because she suspected they might be working with the SSS.

“They are trying to say that I did this for PR for my media company,” Sodikova said.

A high-level media official close to the investigation who asked that his name be withheld told me he thought “Anora made up this story.”

“The investigation showed that there were no records of such people and no calls,” he said. “There were no threats. We are actually wondering why this happened and why Anora claimed this and what was behind all this.”

The high-level media official said that a public announcement and press conference about the results of the investigation would happen soon.

Mad Dogs

President Shavkat Mirziyoyev’s disdain for the SSS is well known. He has called them “mad dogs” and “unscrupulous people in uniform.” He has said he doesn’t trust any security official and would “rip off their epaulets if I have to.” In February 2018, Mirziyoyev said he had received evidence of the torture of two local businessmen in SSS custody in the Bukhara region and promised that the officers would be held accountable.

What the president was talking about was the torture of Dilfuza Ibodova’s two brothers, Ilhom and Rahim Ibodov, while in SSS custody in 2015. Ilhom was beaten to death by SSS officers and other prisoners. Rahim was sentenced to eight years in prison. Even while Dilfuza and her mother were writing letters begging government officials to investigate her brothers’ case, the SSS threatened her not to discuss the case.

Dilfuza Ibdova is a blogger and owner of the website tezkor-yangiliklar.uz in Bukhara. She investigates those who say they were wrongly charged or convicted. She says the SSS do not bother her because several went to prison after they severely beat and tortured her two brothers, killing one. Photo provided by author.

But Dilfuza didn’t back down.

“I was not afraid of anything because I had nothing to lose,” she said.

When the president personally took an interest in the Ibodov case, the perpetrators were brought to justice: six officers and four prisoners were sentenced to prison for up to 18 years; two other officers were found guilty of exceeding their authority, according to the U.S. government and human rights reports. The court proceedings were closed and the decisions were not made publicly available.

Feeling she had the personal protection of the president, Dilfuza, a former kindergarten teacher with no training in journalism, started blogging. In 2020, she registered her media platform with the Agency for Information and Mass Communications, the government’s media monitor. She is the sole reporter. She reports on news, current events and, for a fee, she investigates criminal cases to determine if the charged are guilty. She said she’s not afraid to write about government officials.

“The state security forces are afraid of me,” she told me. “What do you expect when eight of them went to prison? I can write about anything.”

But Dilfuza is one of the few bloggers and journalists who feel this way.

Shuhrat Shokirjonov is the bureau chief of Kun.uz in Samarkand and has 14,000 followers on Twitter. Photo provided by author.

Shuhrat Shokirjonov is the bureau chief for Kun.uz’s Samarkand office. He also blogs on Telegram, Facebook, Twitter, and TikTok. On his social media accounts, he mostly posts his opinions about various social issues and then embeds links to his factual stories on Kun.uz.

Occasionally, he says, the SSS contacts him and tells him to delete material. Two years ago, on May 9 — what used to be called Victory Day and now is called Memory Day — he criticized the government for having a parade. He said the SSS told him to delete the story. “They said that criticizing the parade caused misunderstanding between post-Soviet countries. I didn’t change my mind, but I deleted.”

Shikirjonov avoids writing about the SSS because he knows he will face pressure if he does. Otherwise, he feels mostly free to criticize the government because he always has a reason and provides proof. Still, he says, “I am afraid to be blamed for no reason by the security services.” He is afraid that free expression in the media can be taken away, just like in Russia when President Vladimir Putin suddenly outlawed all media dissent about the war in Ukraine.

Another blogger from Samarkand said he recently moved to Tashkent in part because of the SSS and police surveillance in his hometown. At the beginning of the war, Farukh Turamurodov, who goes by the name Samarkandi online, said he posted on his Facebook page a picture of a car with the symbol Z on its back window. The symbol has become one of support for Russia in its war in Ukraine.

Farukh Turamurodov goes by the name Samarkandi online where he blogs in his spare time about social issues. He said he recently moved from Samarkand to Tashkent because of police and SSS intimidation. Photo provided by author.

An hour later, the SSS contacted him and asked him to delete it.

In 2020, the SSS told him he shouldn’t criticize higher class workers, such as government officials, the president and his family, police and the SSS.

He wrote a post that didn’t name the president but referred to him as the “the man wearing the black suit.” The SSS contacted him and told him to take it down because it wasn’t respectful.

Then last November he complained online about a government app that wasn’t working and he was summoned to the police station. He later learned that two other bloggers were also summoned the same day. It was then that he decided to leave Samarkand.

Bloggers in other regions of Uzbekistan report that they are followed and frequently questioned by the SSS. When I traveled to the Fergana region, the journalists I interviewed and the manager of the hotel where I stayed were contacted by the SSS and asked questions about what I did, where I went, and who I spoke with.

“Pressure from the security services has only gotten worse over time,” explains Bahodirxon Eliboyev, a journalist-turned-blogger in the Fergana region. Government spying and monitoring has had a chilling effect on both journalists and citizens, he said.

“The security services can buy some journalists,” Eliboyev said. “If the authorities order, journalists write everything that officials want. That’s not journalism. That’s propaganda. Censorship is now in our minds and our hearts.”

Bahodirxon Eliboyev runs a Telegram channel blog from Fergana called Ma-News Agency. He was formerly fired from two journalism jobs for writing about controversial topics. He started two magazines but they were also shut down for coverage of controversial topics.

On July 24, 2018, Mirziyoyev’s birthday, Eliboyev said he wrote a blog post wishing the president a happy birthday and asked him not to forget the millions of Uzbek migrant workers in Russia and other countries because they can’t make a living in their home country.

That afternoon four SSS officers pounded on the door of his garage apartment where he was napping, he said.

“When they saw I was living out of a garage, they asked; ‘Don’t you have a home?’ ”

He said he told them: “I can’t work as a journalist. So where can I live? I can’t earn money at the one thing I’m good at.”

They warned him he would go to jail if he kept writing about forbidden topics.

He told them: “I can write whatever I want because your jail is like my garage. But your jail is more comfortable because I don’t need to find bread. You bring me bread. Your jail is for me freedom.” Two hours after our interview, Eliboyev sent me a text. He’d just gotten off the phone with the SSS. They wanted to know what he told me, he said.

First-hand Experience With the Censors

When I came to Tashkent in March, I met with various editors and owners of independent newspapers, including Kamariddin Shaykhov, part owner of the Qalampir.uz media platform where the walls are covered with photos and illustrations of human rights issues, such as domestic violence and government repression. Shaykhov said his media outlet routinely receives letters and warnings from the Agency for Information and Mass Communications telling them to either take a story down or to remove comments on stories.

“Once we get a letter from the Agency, for the next two to three hours, our articles are under three to four times more self-censorship,” he said. “Psychologically it takes a few hours before we are logically thinking. You must fight self-censorship or leave with bruises.”

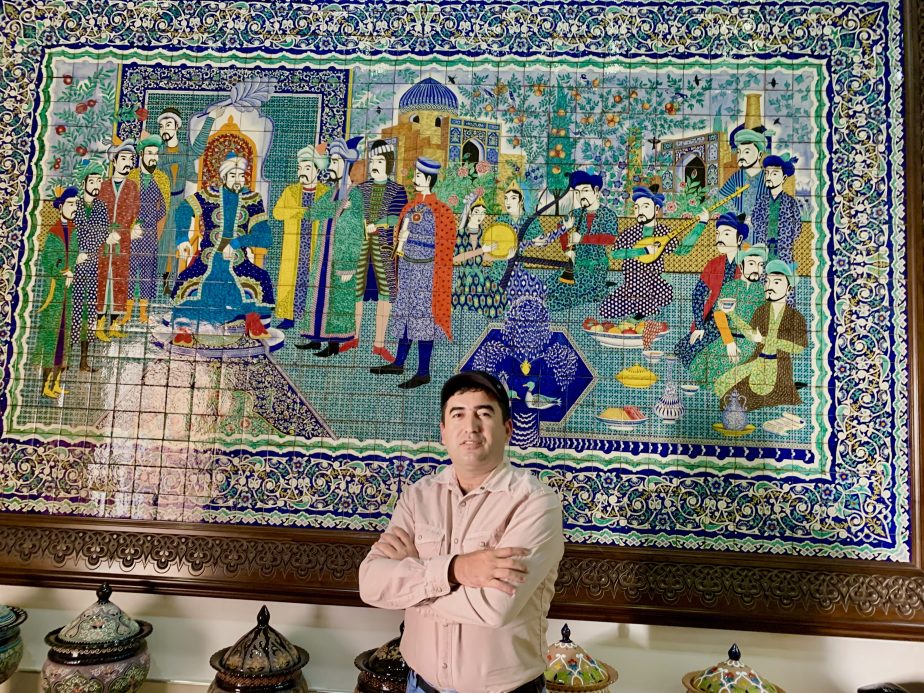

Kamariddin Shaykhov standing before one of the walls in Qalampir depicting Uzbekistani journalists from history. Photo provided by author.

After our meeting, I thought it would be insightful to write for an independent media outlet and see what happened, especially one that was “fighting for freedom of speech,” as Shaykhov professed. I proposed writing a weekly guest column for Qalampir about my interviews with Uzbekistani journalists. Shaykhov agreed since the government had approved my research.

But when I turned in my second column about SSS pressure faced by journalists, including myself, in the Fergana Valley, I was summoned to the Qalampir offices and told that they couldn’t run a story about the SSS. Shaykhov and his “silent” business partner—whose famous singer wife, according to documents, owns 75 percent of Qalampir—defended the actions of the SSS for two hours. How do you know the security services officers weren’t just trying to protect you? How do you know their motives were bad? both men asked.

It was the last I heard from Qalampir.

In an attempt to be fair, I repeatedly requested an interview with the SSS. I sent letters to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Agency.

Dilshod Saidjonov, from the Agency, characterized my request as “naïve.”

“They are so secret they don’t even have a website,” he said. “Even if you got an interview with the security services, there would still be the same problems in Uzbekistan’s media: no will to improve; weak education; and lack of analytical skills.”

Still, I persevered. I asked journalists who knew SSS officers to request an interview for me. I even wrote a blog post on my website about my quest for an interview with the SSS, had it translated into Uzbek, and had several bloggers targeted by the SSS to post it on their blogs. I still did not hear back.