Malaysia, one could say, has been somewhat distracted lately.

With three governments over the last four years, a fractious political environment, ongoing high-profile corruption cases (one involving billions embezzled from state-investment fund 1MDB), and a new general election looming, Malaysians have been mostly focused on domestic affairs.

Now they must contend with a new headache, this time involving the heirs of a long-gone sultanate in the southern Philippines, their own easternmost state of Sabah, and a treaty signed nearly a century before the formation of the country.

On July 12, two Luxembourg-registered subsidiaries of the Malaysian state oil company Petronas were seized by bailiffs on behalf of the heirs of the former Sultanate of Sulu, which was based on a small archipelago in the southern Philippines. The seizures of Petronas’ assets came as the heirs sought to enforce a $14.9 billion awarded to them by a French arbitration court in February.

This award is connected to legal efforts launched by the heirs in 2017 to win compensation over land in Sabah that they claim their ancestors had leased to a British trading company in 1878. The territories of eastern Sabah had originally been under the control of the Sultanate of Brunei, before being ceded to the Sultanate of Sulu in 1658 in return for helping the Bruneians in suppressing a rebellion.

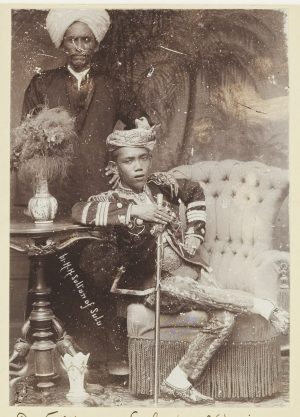

In 1878, then Sulu Sultan Mohammad Jamalul Alam leased North Borneo (as Sabah was previously known) to the British North Borneo Company in return for an annual stipend. Following the end of the Second World War, the British North Borneo Chartered Company would surrender its duties and North Borneo became a British crown colony in July 1946. It was later incorporated into the Federation of Malaysia in 1963.

The Philippines, as successor-in-interest to the Sultanate of Sulu, has maintained a long-standing claim to the state, arguing that the terms of the 1878 treaty were that of a lease and not a transfer of sovereignty. Since 1962, when the Philippines officially filed its claims of sovereignty over the territory, the dispute has remained a stumbling block in relations between Manila and Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia, having inherited the obligations of the 1878 treaty upon its formation, had paid an annual token sum of $5,300 to the heirs of the sultanate. These payments were stopped in 2013 following an armed incursion into Sabah by the armed followers of one self-proclaimed heir, Jamalul Kiram III. The resulting fight with Malaysian security forces would leave some 60 people dead. Following this, the Malaysian government halted the payments, and in 2017 other descendants of the sultanate decided to take legal action.

A day after the seizure of Petronas’ assets, the Malaysian government was able to obtain a stay order against the enforcement of the award after finding its enforcement could infringe the country’s sovereignty. However, lawyers for the claimants have stated that the ruling remains legally enforceable outside of France. The claimants have threatened to seize Malaysian government assets around the world, while under the terms of the award, for every year the award is unpaid the amount is set to increase by 10 percent.

The seizures sparked fury within Malaysia and prompted finger-pointing between the country’s fractious political camps. Malaysian Prime Minister Ismail Sabri Yaakob in March had vowed to fight the court ruling. Following news of the seizures, Sabri stated that a government task force had been set up to protect the assets of not just Petronas but other government-linked companies as well.

Caught in the middle of all of this are the people of Sabah, Malaysia’s poorest state. By official counts, Sabah recorded the highest percentage of absolute poverty within Malaysia in 2020 at 25.3 percent, an increase from 19.5 percent in 2019). The relative underdevelopment of the oil-rich state has long been a source of frustration for Sabahans vis-à-vis the more economically developed western half of the country, helping stimulate calls for greater autonomy for the state.

This latest incident involving Petronas’ assets is only expected to worsen these feelings of marginalization. “Most Sabahans feel that the Malaysian government dropped the ball on this,” says James Chin, professor of Asian studies at the University of Tasmania. “They are angry that this dispute over Sabah has not been resolved yet.”

Chin references the so-called Project IC, an alleged covert operation carried out in the late nineties by the Malaysian government to dramatically increase the number of Muslim citizens within Sabah to ensure the federal government’s control over the state. This was done by illegally giving Malaysian citizenship to non-Sabah born Muslims, with the majority going to Moros (Muslims from the southern Philippines). As Chin stresses, for many Sabahans controversies such as Project IC tie in with what is happening now.

“Sabahans are very passionate about this dispute because apart from national sovereignty, they believe their livelihood is threatened by an overwhelming presence of non-citizens out to take advantage of limited resources,” observes Zam Yusa, the Malaysian Borneo-Southern Philippines Correspondent for Al Aan TV.

And what about the Philippines? Could this latest saga embolden Manila? Indeed, not too long ago the now-former Philippines’ Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jr. raised the ire of the Malaysian government when he fired off a series of provocative tweets proclaiming the Philippines’ ownership of Sabah.

As per one analysis, that reassertion of Filipino claims over the territory could have been a way to deflect domestic criticism over the former Duterte administration’s perceived acquiescence to China with regard to the South China Sea dispute. Could the recent seizures encourage Manila, under the new government of Ferdinand Marcos Jr., to try to stake its claim again?

Chin believes it is unlikely: “My understanding is that he [Marcos Jr.] wants this on the backburner. He will not drop the claim, but will not actively pursue it either.”

Oil wealth aside, Sabah’s sensitivity to both Malaysia and the Philippines is also predicated on its importance to regional security. As noted in a recent piece for The Diplomat, Sabah’s porous borders with the politically unstable southern Philippines has made it a prime target for cross-border terrorist activities, kidnappings, and illegal immigration. The 2013 armed incursion continues to haunt the state, and as the authors of the piece argued, Malaysia may very well need to prepare for another possible incursion by militant groups.

Ultimately, this extraordinary incident can only serve as a further sore point for the people of Sabah, already beleaguered by the region’s marginalization and place within the country. As for ASEAN, already divided over hot-button topics such as the Myanmar crisis and the growing Sino-U.S. competition, possible tensions between two of their founding members may be the last thing they need.