The killing of al-Qaida chief Ayman al-Zawahiri in a U.S. drone attack in downtown Kabul on July 31 will have far-reaching implications for the Taliban’s ties with the United States and al-Qaida. Al-Zawahiri was living in a Taliban safe house with his family since April.

His killing indicates that he had a sanctuary in Taliban-ruled Afghanistan where he was issuing video statements, overseeing the revival efforts, and advising the Taliban’s de-facto regime. His death came a fortnight ahead of the first anniversary of the Taliban capturing power in Kabul.

Various U.N. reports had indicated that al-Qaida enjoyed freedom of action and movement in Afghanistan under the Taliban’s protection. Though both militant groups publicly downplay their ties, they are closely allied and still coordinate with each other.

Soon after the Taliban signed the Doha Agreement in 2020 with the United States, al-Qaida congratulated the Taliban and celebrated the Taliban’s victory as its own. Al-Zawahiri’s killing will shake the international community’s confidence in the Taliban’s counterterrorism commitment under the Doha Agreement.

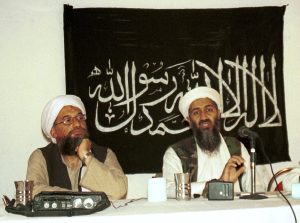

Al-Zawahiri took over as al-Qaida chief in 2011 after the killing of the group’s founder Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan. Unlike bin Laden, al-Zawahiri lacked charisma and ideological appeal among al-Qaida followers. However, he was known as a competent manager with exceptional organizational skills. He led al-Qaida during its most turbulent times when a large number of its leaders were killed in the U.S. drone attacks in the Afghanistan-Pakistan border region. During this period, al-Qaida’s Iraqi affiliate, the so-called Islamic State, broke away and declared its self-styled Caliphate.

In the face of these organizational and leadership setbacks, al-Zawahiri not only kept al-Qaida’s brand of global jihadism alive, but he also expanded it through the franchising strategy to South Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

Though organizations like al-Qaida prepare in advance for leadership decapitations by having a clearly defined line of succession, replacing al-Zawahiri will not be an easy task for a number of reasons. First, since its inception in 1988, this is the second occasion that al-Qaida will have to choose a new leader.

Second, al-Zawahiri’s two deputies, Saif al-Adel and Abd al-Rehman al-Maghrebi, live in Iran. If one of them is appointed as the new al-Qaida chief, it will be ironic for a Salafi-jihadist group to have its leader stationed in Shia Iran.

Third, both Iran and Afghanistan, especially after al-Zawahiri’s killing, are not safe for al-Qaida. In November 2020, Israeli agents killed al-Qaida’s number two Abu Muhammad al-Masri in Tehran. At the same time, Syria is equally not safe as a number of al-Qaida leaders have been eliminated there as well. Al-Qaida will keep these factors in view while choosing its new leader. Given the above, it is unsurprising that despite a clearly defined line of succession, al-Qaida has not yet announced its new leader.

On the whole, al-Zawahiri has left a mixed legacy. On his watch, al-Qaida failed to launch a high-profile attack against the West. An entire generation of al-Qaida leaders was killed during his tenure as al-Qaida chief. Likewise, al-Qaida became more circumspect and defensive, focusing on localization and regionalization of its jihadist doctrine. Under this approach, al-Qaida extended help to local Muslim insurgent groups like the Taliban.

Some al-Qaida watchers are of the view that al-Zawahiri’s killing might be a blessing in disguise for the group. His successor can capitalize on al-Zawahiri’s consolidation and rebuilding efforts by shifting al-Qaida from defensive to offensive mode. It is important to mention that while navigating the leadership succession, al-Qaida is at an inflection point. It is both an opportunity and a challenge for the global jihadist group; it will either rise from here or the new leader will preside over its decline. Al-Zawahiri’s status quo is unlikely to persist.

Al-Zawahiri’s killing in a Taliban safe house will impact al-Qaida’s ties with the Taliban’s de facto regime. As a consequence of the drone attack, the remaining al-Qaida leaders and fighters in Afghanistan will go underground for the foreseeable future. Some al-Qaida leaders would view al-Zawahiri’s killing as the Taliban’s incompetence, while others would see it as their covert complicity with the U.S. under the Doha Agreement.

His killing will also impact the U.S.-Taliban ties in the short term. The U.S. is unlikely to abandon Afghanistan and a limited engagement policy under the least-common-denominator approach will continue.

However, the Taliban regime’s efforts to get international recognition will hit a dead end. Likewise, the backend negotiations between the U.S. and the Taliban to unfreeze $3.5 billion of the Afghan assets will also be in the doldrums. Finally, al-Zawahiri’s killing will also rekindle a debate within the Taliban between the movement’s pragmatists and hardliners about their future stance toward al-Qaida.

Taliban pragmatists advocated distancing the group from al-Qaida, focusing on the challenges of governance and on transitioning from insurgency to politics, as opposed to hardliners who advocate continued association with al-Qaida.

In recent years, the threat from the global jihadist movement has diminished considerably as both al-Qaida and IS lost their top leaders and suffered organizational setbacks. However, in the era of great power competition where counterterrorism is not the top priority, continued monitoring of groups like al-Qaida and IS is necessary to mitigate their threat.