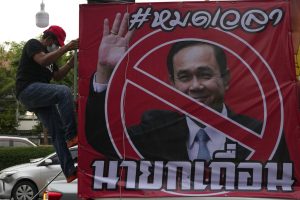

After Wednesday’s Constitutional Court ruling, Prayut Chan-o-cha stepped down as Thailand’s prime minister, giving way to caretaker Prime Minister Prawit Wongsuwan, who has, since the planning of the May 2014 coup that brought them both to power, been his deputy. Long regarded as the architect of the military-backed putsch, Prawit takes the helm tarred by past scandals, sporting a poor image with the Thai public, and having been associated with a government that has been hounded by protests and political upheaval.

Since the ruling, journalists and commentators speculated on what the Constitutional Court’s decision means for Thailand, for Prayut himself, and for a ruling coalition that has faced a slew of political challenges. All that is known is that as of August 24, Prayut’s powers are suspended until the Court rules on a petition that has been filed by the opposition, arguing that he has exceeded the constitutional limit of eight years in office and should step down. The process could take as long as two months. A common message among pundits was that the Court’s decision was a surprise. For example, Titipol Phakdeewanich of Ubon Ratchathani University suggested that the decision was a “strategic game to make the establishment look good and at least restore the trust in the constitutional court.”

Titipol not only misses the point, but fails to reflect properly on the nature of the Thai judiciary. Yesterday’s ruling, or a decision on his tenure as prime minister two months from now, will not restore legitimacy to the Constitutional Court. That would require a long, slow process marked by major institutional reforms and a transparent, apolitical selection and nomination process, and in which rulings could be debated and digested by the Thai public. Moreover, to make reasonable assumptions on how the Court will rule or how that ruling will affect Thai politics, it is important to understand the Court’s composition, if not its ideology.

First, there have been a number of important studies on the Thai Constitutional Court that have shed light on how the Court may eventually rule on the petition to potentially end Prayut’s eight years in power. In 2018, Professors Björn Dressel of Australian National University and Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang of Chulalongkorn University conducted an analysis of the Constitutional Court’s work between 1998 and 2016. They seemed to confirm some of what many have been suggesting for years, that there are serious ties between entrenched political elites and the judiciary, resulting in a highly politicized court. In academic circles, the most recognizable study was that of Eugénie Mérieau, a brilliant French scholar who in 2016 contended that the Thai “Deep State,” a loose network of actors who are opposed to the rise of electoral politics, used the Constitutional Court as a kind of “surrogate king” in attempting to combat the challenges of democratization, political empowerment, and electoral representation.

Connectivity between pro-monarchy and pro-conservative political elites and the Constitutional Court is also seen in a number of more recent cases. The March 2019 Thai Raksa Chart case as well as the November 2019 case against opposition politician Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit are illustrative of this. After Thai Raksa Chart tapped the older sister of King Maha Vajiralongkorn, Princess Ubolrattana, as its nominee for prime minister, the Constitutional Court moved at lightning speed, and within the space of a month, ordered the party dissolved.

In the case against Thanathorn, the conventional wisdom was that he and his Future Forward Party, who had made critical comments about the military, were clear threats to established conservative interests, as well as the foundational changes the Palace and the military had made to Thailand’s electoral system. Predictably, Thanathorn was hit with an assortment of politically-motivated charges, and again, like in the Thai Raksa Chart case, the Constitutional Court moved swiftly to suspend his status as a member of Parliament and later dissolved Future Forward altogether.

These cases demonstrate two things. The first is that connectivity between conservative political elites and the Thai judiciary suggests that the Constitutional Court ruling on the petition against Prayut is less of a “surprise” than Titipol or other analysts might suggest. Second, if voting behavior is consistent with that of the past, the court is likely to render a decision in keeping with the pro-conservative tradition. In other words, the eventual verdict isn’t likely to send shockwaves through Thailand’s political system.

Prayut’s future might be up in the air, but it is highly likely that the existing system will survive intact. In what alternate universe did yesterday’s decision actually build public faith and legitimacy in the Constitutional Court? While it was created from the People’s Constitution of 1997 as a product of democratization, it has slowly devolved into just another decaying Thai institution.

As Mérieau might argue, the Constitutional Court is very much a part of the reason why Thailand is in this predicament to begin with. The Court, like many other Thai institutions, including the Royal Thai Police, the Election Commission, the National Anti-Corruption Commission, and the National Human Rights Commission, are all in a state of decline and to varying degrees serve at the pleasure of established political elites. For example, after the Constitutional Court gave credibility to the referendum that brought Thailand its current constitution (drafted by the military with final input from the King), it crippled Parliament by requiring an almost impossible legislative goal of a two-referendum requirement to make any amendments to the 2017 Constitution or to draft a new charter.

In no way did the Constitutional Court suggest in its ruling that its willingness to look closely at the opposition’s petition meant it was attempting to appease the Thai public or give a political victory to democratic activists. Given its history, it is more likely that this is an opportunity to give finality to an argument that requires a legal and political solution. By concentrating solely on Prayut’s future as prime minister, we are ignoring the larger problem. Instead, this should be a golden opportunity to give broader public scrutiny to a Thai judiciary that is brittle, bereft of independence, and openly hostile to democracy.