Despite the fact that men constitute the majority (55 percent) of people living with HIV in Uzbekistan, it is women who are disproportionately affected by the virus and related socioeconomic issues. Because of the inequalities that influence every aspect of their life, it is more difficult for women to have access to information about HIV and its transmission, to test for HIV, to receive a consultation, or to access treatment.

Gender inequality and stereotypes, especially in health, education, and command over economic resources, make women more vulnerable to HIV and to other related conditions. It is also, for example, mostly women’s burden to take care of HIV-positive family members.

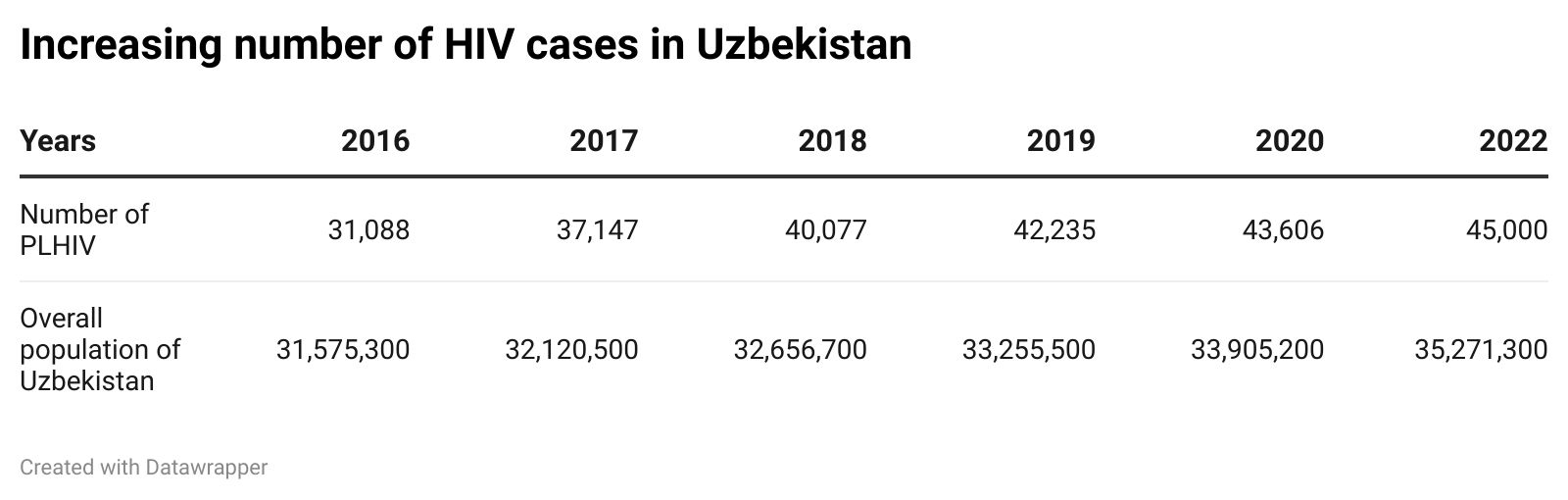

Uzbekistan registered its first case of HIV in 1987 and, until 1998, only 51 people were reported HIV-positive in the country. Over the past eight years, the number of people living with HIV in Uzbekistan has steadily increased from 31,088 in 2016 to an estimated 45,000 in 2022, following a similar trend to the demographic growth observed in the same period.

Forty-five percent of those living with HIV in Uzbekistan are women. The gender imbalance in HIV cases is formally explained by endemic regional and internal migration factors: More men than women migrate, either abroad or within the country, and men are more likely to engage in risky behaviors and contribute to the spread of HIV once back home. Labor migration has been prevalent for a long time in Uzbekistan – as of 2022, official data reports 1.8 million Uzbek labor migrants registered in Russia alone. But this explanation further stigmatizes migrant behavior, conveying the message that migration is somehow a key factor behind the HIV epidemic in Uzbekistan.

Data sources: Number of people living with HIV (Ochiq Ma’lumotlar Portali. OIV bilan yashayotgan odamlar. n.d.) Overall population of Uzbekistan (Uzstats. Doimiy aholi soni. May 31, 2022.)

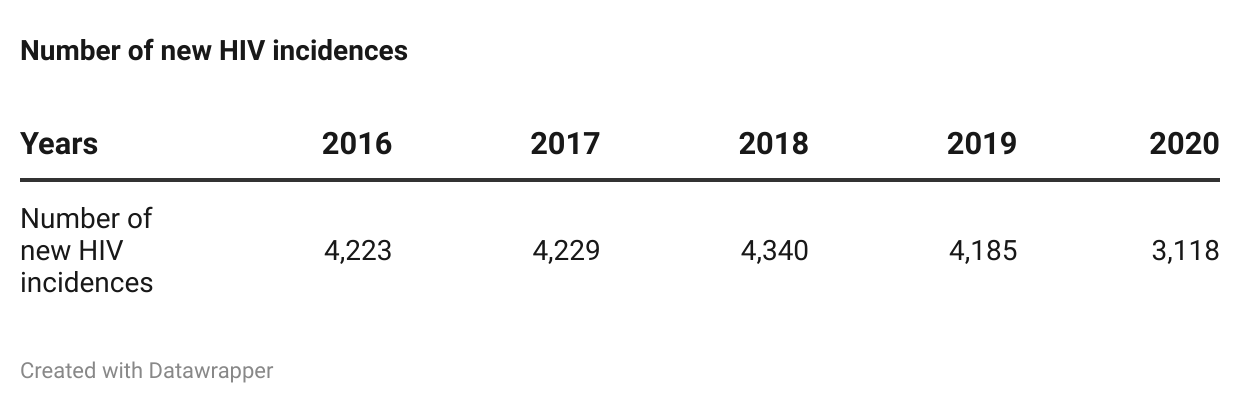

Uzbekistan’s HIV epidemic is at what’s called a concentrated stage, in which HIV has spread rapidly among specific groups, but is not endemic and established in the general population. The rate of spread has been on the rise in the past 20 years: Every year an average 3,500 to 4,000 new cases are registered.

Data source: Ochiq ma’lumotlar portali. “OIV bilan kasallanish.” n.d.

HIV concentration is highest in Tashkent city (10,484 people living with HIV in 2020), Tashkent region (6,560), Andijan region (6,870), and Samarkand region (4,080). It is most prevalent in urban, densely populated areas. For example, as of 2022 the population density in Tashkent region is 194.3 people per square kilometer; in Samarkand and Andijan regions it is 240.3 and 756.2, respectively; in Tashkent city it reaches 6,379.1 inhabitants per square kilometer. Internal migration also plays a role in HIV prevalence in urban areas, especially in Tashkent, as people move from rural areas to urban spaces in search of work.

Up until the 2010s, the dominant mode of HIV transmission in Uzbek society was through injection drug use: in 2011, drug injection was responsible for 44.6 percent of transmissions, while 37.2 percent happened through heterosexual contact and 3.7 percent through mother-to-child transmission. Over the past decade, however, sexual transmission of HIV has taken over, especially among young people. In 2020, 74,9 percent of registered HIV cases in Uzbekistan were transmitted sexually, and, according to the government of Uzbekistan, as of 2021, 25 percent of new HIV cases were registered among young people between 18 and 30 years old.

Key Populations and Vulnerable Groups

UNAIDS identifies men who have sex with men, sex workers and their clients, people who inject drugs, and their partners and families as key populations at higher risk to be affected by HIV. Other groups, including migrants and young people, are not strictly part of these key populations, but are still targeted by HIV interventions and awareness-raising as some of their members tend to engage in risky behaviors.

While information on the size of the key populations is not available, according to the latest data, HIV prevalence is 3.2 percent among sex workers and 3.7 percent among men who have sex with men. Both groups are subject to public stigma and hatred due to religious and traditional values practiced by wider Uzbek society. They constantly experience naming and shaming, threats, and extortion by members of society (including neighbors, friends, and family members), in healthcare, and sometimes by representatives of law enforcement.

It is worth noting that a lack of comprehensive sexual education in schools also limits access to knowledge regarding HIV among youth and prevalent stigma towards people living with HIV. Classes on health and lifestyle present at public schools do not provide comprehensive sex education, especially in terms of safe sex practices. Along with many teachers sharing outdated information, this contributes to perpetrating stigma toward HIV, people living with HIV, and ignorance about the epidemic.

HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs was 5.1 percent in 2018. The overall number of people who inject drugs is unclear, but drug abuse seems to be especially problematic among the youth. As of 2020, official data indicated 5,889 registered drug users among the youth. However, some speculate that the real number could be ten times higher. Most young people who use drugs, according to government lists, are in Andijan (1,232) and Ferghana (1,093) regions, as well as in Tashkent city (1,188).

At present, there is no disaggregated data or information available on the gender breakdown of this particular group. Based on women’s share in registered drug-related crimes, it is possible to suggest that injection drug users tend to be more men than women: Between 2007 and 2021, women’s involvement in drug-related crimes dropped from 12 percent to 3.4 percent. Similarly, in 2020, when 4,722 drug-related crimes were registered, only 120 women were eventually charged, as opposed to 3,403 men. However, this does not necessarily mean that, among people who inject drugs, men are more at risk of acquiring HIV than women.

HIV prevalence among prisoners is even more disputable due to an almost lack of accessible reliable data. As of 2022, there are 54 penal colonies in Uzbekistan that host over 29,000 inmates. This is a sharp decrease from 2014, when the BBC reported 64,000 prisoners held in such facilities.

Disaggregated data about the number of prisoners, both by sex and age, is not available. However, considering the share of women engaging in criminal activities is much lower than that of men, it seems fair to assume that women prisoners are significantly fewer than their male counterparts. In 2021, women were responsible for 12.2 percent of overall crimes committed in Uzbekistan – down from 14.8 percent in 2007.

The latest available data (from 2018) shows an estimated 0.5 percent HIV prevalence among prisoners in Uzbekistan. Although prisoners can access antiretroviral (ARV) therapy, no opioid substitution therapy (OST) or needle/syringe programs (NSP) exist.

Testing and Treatment

As of 2021, an estimated 76 percent of the people living with HIV in Uzbekistan are aware of their HIV status. HIV testing in Uzbekistan is free, and the procedure is carried out according to the Ministry of Health’s guidelines. Medical personnel must ensure the confidentiality of the personal information of those testing for HIV. It is carried out on both a voluntary and mandatory basis. For example, couples applying for a marriage license must undergo certain medical examinations, including HIV testing. Mandatory HIV testing is established also for donors of blood and biological fluids, pregnant women, citizens suspected of injection drug use, children born to HIV-infected mothers, and persons whose sexual partner has been diagnosed with HIV.

As of 2020, there are 78 HIV diagnostic laboratories operating in the country. To support their work, the state allocates over 8 billion Uzbek som (approx. $72,617) every year.

The number of people getting tested for HIV has been gradually increasing. In 2008, only 800,000 people tested for HIV. By 2017, the figure reached 3.2 million people.

Uzbekistan tests around 600,000 pregnant women for HIV annually. And about 550-600 children are born to women living with HIV every year. To prevent transmission of HIV from mother to children, both mothers and newborns have access to ARV. Newborns also receive baby formula for the first six months, rather than breastfeeding. As a result of these and other measures, by 2015, the share of HIV-free children born to women living with HIV officially reached 98-99 percent.

Uzbekistan has also increased funds allocated for HIV treatment on an ascending order for 2018-2022. For 2022, the allocated budget was $8.54 million (up from $2.38 million in 2018).

By 2021, a total of 30,019 people, an estimated 51 percent of the total living with HIV in Uzbekistan were receiving ARV. More women living with HIV than men undergo ARV: 80 percent of women living with HIV over age 15 are on ARV compared to only 40 percent of HIV-positive men in the same age category.

Gendered Socioeconomic Inequalities as Drivers of HIV Among Women

Over the past two decades, Uzbekistan has committed to raising public awareness of HIV transmission, diagnosis, and treatment. However, considering the patriarchal culture, it would be fair to assume that fewer women than men have a high degree of awareness about HIV, especially in rural and isolated areas.

Patriarchal norms come in many forms, but the one that limits women’s choices the most, exposing them to socioeconomic and health difficulties, including HIV, is decision-making. Many women across Uzbekistan cannot make their own decisions in everyday life. Experts report accounts of young women battling severe health conditions still needing their husband’s permission to leave the house to see a doctor. While there are exceptions, especially in urban areas, in general, women are still dependent on men’s decisions. Most women, particularly in villages, can study, work, visit healthcare institutions, and have a social life only with permission or under the supervision of the men of their household. This even applies to having a smartphone, let alone using social networking websites or connecting with the outside world by any other means. While global and local HIV awareness campaigns are slowly moving to the online space, this mode cannot reach isolated women living under such strict patriarchy.

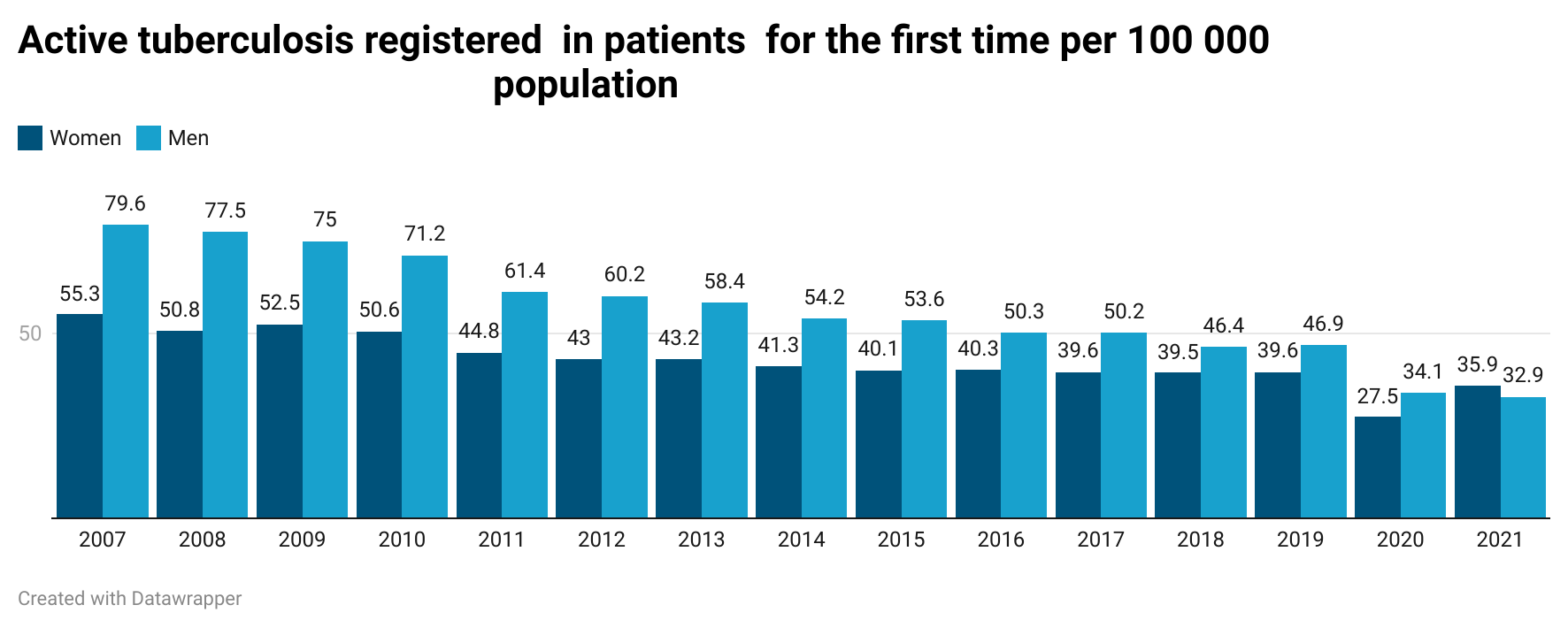

To cite another relevant example: Incidences of tuberculosis have been steadily decreasing in Uzbekistan, yet the decrease in women’s tuberculosis rates has been slower than men’s – from 55.3 to 35.9 cases per 100,000 women and from 79.6 to 32.9 cases per 100,000 men between 2007 and 2021.

Women living with HIV are also more likely than other women to contract the human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, which may lead to cervical cancer. Globally, 6 percent of women with cervical cancer also live with HIV, while less than 5 percent of all cases of cervical cancer are caused by HIV. In Uzbekistan, 1,660 women are diagnosed with cervical cancer every year, and 585 women die from it.

Gender disparity in access to economic resources is also significant as it is the most prominent reason women are so dependent on men. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, women-led household income was 17 percent lower than men-led households. During the pandemic, 42 percent of women-led families reported that they would not be able to cover an unexpected expense of 100,000 Uzbek som (less than $10), as opposed to 25 percent of men-led households. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the official unemployment rate for women was 13 percent while for men it was only 6 percent.

It is more difficult for Uzbek women to have a sustainable job than for men. Many take maternity leave of up to three years for each child, until the children can attend a daycare. Additionally, marital status significantly decreases women’s access to work, as they feel the social pressure of local traditions dictating that they take care of the household instead of working. A study conducted within the O’zbekiston fuqarolarini tinglash (Listening to the citizens of Uzbekistan) project found that the employment rate is higher among unmarried women (52 percent) than among married women (36 percent).

Uzbek women tend to become housebound upon marriage: All household responsibilities, from taking care of the house to the bulk of childcare and looking after elderly relatives of the household, are a responsibility of the woman. Unsurprisingly, 43 percent of women who are not working and not looking for a job said that their employment status is directly caused by their responsibility to take care of the household, while only 7 percent of men cited the same reason.

Many families across the country are heavily dependent on remittances sent by family members, mostly men, working abroad. Many men, spending months or years at a time away from their families, engage in risky behaviors, such as using the services of sex workers or using injection or other types of drugs. At the same time, undocumented migrants lack access to healthcare, and migrants testing positive for HIV in Russia are deported and placed in a re-entry blacklist. All these issues pile up and eventually increase migrants’ risk of becoming HIV-positive without being aware of it, without getting tested, and without accessing proper treatment. This may also result in returning migrants passing HIV to their wives and families once back in Uzbekistan.

The higher incidence of sexually transmitted HIV reflects dynamics of gender-based violence, especially domestic violence, increasing women’s vulnerability to HIV even more. Violence against women and girls is part of many women’s daily struggles in Uzbekistan. While the link between gender-based violence and HIV risk is indirect and passes through gender inequality in access to information and services, sexual violence is directly linked to a higher risk of becoming infected with HIV. In 2021 alone, law enforcement bodies in Uzbekistan registered almost 40,000 cases of abuse toward women (up from 15,000 in 2020) with more than 80 percent of violence taking place at home. In most cases, the perpetrators are husbands.

These examples are all indicators of gender inequality in socioeconomic life, where women are in a disadvantageous position and more dependent on men. Gender inequality increases women’s vulnerability to HIV and thus these issues need to be considered and addressed when developing and implementing the national HIV response.

The article is based on the “Gender Assessment of the national HIV response – Uzbekistan” – a policy report written by Niginakhon Saida and proofread and edited by Sara Scardavilli for the UNAIDS Uzbekistan Country Office. The report is available here.