Today is March 8, International Women’s Day. Today, women in Central Asia will receive special gifts, flowers, and positive attention. At the same time, violence against women and gender inequality remains disturbingly prevalent across the Central Asian region.

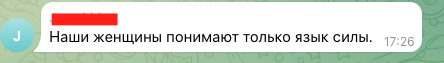

Last summer, social media users in Central Asia were shocked when a video from an Uzbekistani wedding party emerged showing the groom publicly slapping his bride after she had won in a little party game. In the comments under the Telegram video, some people (mainly women) were scandalized by the violent act, but others posted comments like: “Our women only understand the language of force.”

Central Asian governments publicly declare that they are fighting against this mindset, with varying degrees of commitment and success.

Unreported Violence in Kazakhstan

According to data from the Bureau of National Statistics and the Zertteu Research Institute, around 60 percent of women aged 15-49 in Kazakhstan have experienced partner violence. The situation was exacerbated during the pandemic and lockdown — see, for instance, International Partnership for Human Rights’ (IPHR) joint report with Kazakhstan International Bureau of Human Rights and Rule of Law (KIBHR). Today, the problem remains critical, with research indicating serious underreporting. Some 70-90 percent of women do not turn to the police, or refuse to lodge a complaint about domestic violence.

Femicide in Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan struggles with entrenched problems of misogyny and femicide. U.N. Women identifies driving factors as “stereotyped gender roles, discrimination towards women and girls, unequal power relations between women and men, or harmful social norms.”

In an award-winning investigation, Kloop journalists described how one middle-aged Kyrgyz man who killed his wife stated that he had no regrets as she had been a slow cook and turned off the TV while he was watching. The investigation found that most women who were killed by their husbands were already in abusive relationships. According to Tolkun Tyulekova, the head of the Kyrgyz Union of Crisis Centers, many women in abusive relationships choose not to press charges against their partners, in part due to pressure from relatives to stay silent.

Turkmenistani Women Believe Violence is Deserved

A joint state-UNFPA study on domestic violence in Turkmenistan in 2021 interviewed 3,000 women and found that around 12 percent reported experiencing partner violence, and over 41 percent experiencing social control. Most disturbingly, 60 percent of women interviewed stated that failure by women to abide by societal norms was grounds for a husband to beat his wife, and that sexual violence within marriage is not perceived as a violation due to cultural views on marital obligations. As in other Central Asian countries, relatives pressure women to stay quiet about their ordeals.

The Turkmen Initiative for Human Rights (TIHR) reported that the study was unusually candid, and expressed hope for positive change now that the state had recognized the problem.

Obedient Tajikistani Women

Tajikistan also faces serious and widespread problems of gender-based violence. The U.N. Human Rights Council reported in 2019 that as many as 8 out of every 10 women in Tajikistan experienced domestic violence at least once in their lifetime. However, is very difficult to find the exact extent of domestic violence in Tajikistan because the government does not publish comprehensive statistics about it. Also, many women do not report the abuse and prefer not to talk about it because they are afraid or ashamed (only 1 in 10 women take action to stop the violence). There is great social pressure to keep domestic violence a family secret.

There are frequent stories in the media of how Tajikistani women are objectified and perceived, by society and officials alike, as submissive caretakers, and that girls are brought up according to these values. “Nigora, like other parents in our country, developed in her daughter the qualities demanded by potential suitors, such as submission, modesty, obedience, and the ability to cook,” a mother explained to the Tajikistani news outlet Asia Plus. Challenging these accepted norms can be risky for women, and thus many women choose to stay with abusive husbands, fearing the societal stigma of leaving.

Seeking New Solutions?

According to World Bank’s Regional Director for Central Asia, Tatiana Proskuryakova, empowering women and girls and tackling the underlying reasons for gender-based violence is the only way for the region to fulfill its economic potential. With the help of international partners, Central Asian states are seeking new ways to tackle the problem.

For example, in November 2022, an “abuser center” opened at a public health clinic in the northern city of Khudjand in Tajikistan. It is a tiny clinic, where psychologists and lawyers work to help violent abusers to change their ways. Muharrama Makhimov, psychologist at the center, explained that working with abusers is a part of the solution, beyond just holding them criminally liable for their actions.

There are also numerous initiatives to help women affected by domestic violence navigate their situation and understand their rights, although progress is being undermined by remaining protection gaps in legislation, weaknesses in the criminal justice systems, and the failure of the authorities to address the widespread problem in a systematic manner. Local grassroots initiatives, such as those of our partners in Khatlon, Tajikistan, are working to help affected women through self-help groups and aiding women in earning a living.

In Kazakhstan, students are also helping develop a mobile application, which is disguised as a book reader app but allows victims of violence to contact trusted people, crisis centers, or law enforcement.

There is much that Central Asian states must do to address the problem of gender-based violence. At least the newlywed young Uzbekistani couple received counseling following the incident, after the groom was convicted of petty hooliganism. But against the entrenched societal problem of men believing that women only understand “the language of force,” a counseling session seems an ineffective band-aid. For instance, we gave specific recommendations to the Uzbek authorities in a joint briefing made last year with our partner NGOs in Uzbekistan, to “adopt a comprehensive strategy to eliminate discriminatory stereotypes and patriarchal attitudes about the roles and responsibilities of women and men; and use innovative measures targeting the media to strengthen understanding of gender equality.”

Central Asian governments must step up and fulfill their obligations to provide a robust response to domestic violence, equal protection to survivors of abuse and protect women’s rights both in policy and practice.