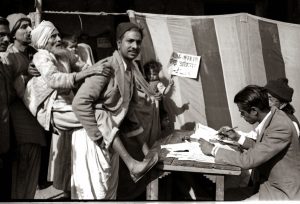

In the run-up to hosting the G-20 summit this year, India has begun marketing itself as the “mother of democracies.” Prime Minister Narendra Modi began to emphasize this idea last year, both domestically—in Parliament—and internationally, at the United Nations. Is this hyperbole, similar to nationalistic claims that “ancient Indians had spacecraft, the internet, and nuclear weapons,” or is there some truth to the prime minister’s statement?

The reality is complex. Ancient India certainly had democratic and republican states, but so did ancient Greece, Rome, and a host of other places. David Stasavage, dean for the social sciences at New York University characterizes early democracy in his book “The Decline and Rise of Democracy: A Global History from Antiquity to Today” as a system where “those who ruled needed to obtain consent from a council or assembly” and where “rulers simply did not inherit their position: there was some way in which rising to leadership required the consent of others.” According to Stasavage, “early democracy was so common in all regions of the globe that we should see it as a naturally occurring condition in human societies.”

Contrary to the linear narrative that democracy was invented once, in ancient Athens, before being rediscovered and spreading, democratic government was more common in the ancient world than many believe, although the proportion of the population participating in Athenian democracy may have been more extensive than other places. Even then, in Athens, only free, adult male citizens could vote and participate in government — around 10 percent of the population. In the fourth century BCE, this was about 30,000 males out of a population that included 160,000 citizens, “25,000 resident aliens, and at least 200,000 slaves.”

Government by assemblies and councils was relatively common throughout the ancient world, particularly in tribal societies, but also in early states. According to Stasavage, the spread of complex states with bureaucracies is correlated with the decline of early democracy, and early democracies tended to thrive in out-of-the-way places. The spread of technology, faster transportation, and writing also helped establish centralized states that diminished democracy. Athens and the Roman Republic were initially situated far away from the heartlands of state formation in the ancient Middle East. In India, democratic states were particularly common in hilly areas, such as the Himalayan foothills. Republican and democratic states were found in ancient Rome, Carthage, Mexico, India, the Hurons in North America, ancient Mesopotamia, and parts of Africa. The Greek historian Herodotus also claimed that the Persians considered abolishing monarchy and establishing democracy during the 520s BCE. The English assemblies that became Parliament were also a local development, independent of the Greek example, as feudal England had a weak state and little bureaucratic apparatus. It was only in the last couple of centuries that strong states with both democratic governance and competent bureaucracies were established in the wake of the American and French revolutions.

The presence of democratic governance in ancient India should therefore not be a surprise, particularly given the region’s history of weak states. The writings of the ancient grammarian Panini, the Mahabharata, and Buddhist literature all refer to states with assemblies (sanghas), some of which were republics, including the Shakya Republic, where the Buddha was born. Many of these republics lasted centuries, from around 600 BCE to 300 CE, although medieval Hinduism became associated with hereditary, godlike kingship. Not much is known about how these republics were run, but some seem to have incorporated members from across castes and classes. In a conversation between the Chancellor of Magadha and the Buddha, the Buddha mentioned that the Vijji Republic of eastern India held full and frequent public assemblies, which met “together in concord…[and carried] out their undertakings in concord” and acted in accordance with the ancient institutions of the Vajjians.

There are also examples of kingdoms that then became republics. For example, what was once the Kuru Kingdom in northwest India later became the Yaudheya Republic; this is known from inscriptions referring to elections for a maharaja (great ruler), and references to the polity as a “gana,” a Sanskrit word meaning a group of people that frequently also is used to indicate a republic. The Yaudheya Republic may have been run by aristocrats and elites — similar to the Roman Republic — as the name derives from Sanskrit yoddha, meaning warrior. While there may be a gap of several centuries between these ancient Indian republics and the modern Indian state, the same is true of a place like Greece, which was ruled autocratically for millennia during the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman Empires. In the case of India, having a local precedent certainly helps in assimilating and localizing the concept of modern representative democracy.

Democratic tendencies in India became more established at the village level. Villages were quite often run by councils, panchayats, which had become quite prominent by the Gupta era (late 200s-late 500s CE), during which, in “the absence of close supervision by the state, village affairs were now managed by leading local elements, who conducted land transactions without consulting the government.” It was simply easier and more efficient for villages to run themselves, with governments providing only security and taking tax revenue, the collection of which was often delegated to local councils. Village councils took care of banking, the construction of public utilities, and civil law, according to Chola and other South Indian inscriptions from around 1000 CE. Village councils persisted throughout the eras, regardless of who ruled over India, and still exist in a modified form today—their existence was incorporated into the formal structure of India’s governance through the Seventy-third Amendment in 1992.

Democracy has ancient roots throughout the world. While no one place can be called the “mother” of democracies, it is certainly true that Indian democracy is as ancient as Greek democracy and that both evolved independently, as did other states with assemblies throughout the rest of the world. Instead of conceiving of democracy as something that was invented, it is better to think of it as one of the elemental forms of government common to all of humanity.