Sri Lanka’s debt default – announced in April of last year amid foreign currency shortages that had triggered rolling blackouts, fuel queues, and street protests – has been subject to endless debate by local and international observers. The root causes of the country’s debt problem have been attributed to various factors, including corruption and nepotism, alleged predatory lending from China (the so-called “Chinese debt trap”), and a structural balance of payments deficit. These debates aside, it is increasingly clear that the immediate cause for Sri Lanka’s collapse is the structure of the country’s debt itself – specifically, its deep and growing exposure to international sovereign bonds (ISBs) issued at high interest rates.

In the immediate aftermath of Sri Lanka’s civil war in 2009, the country embarked on a mainly bilaterally-financed infrastructure investment program. However, alongside these borrowings for investments in ports, energy, and transport, the Sri Lankan government also binged on international sovereign bonds, issuing $17 billion worth of ISBs from 2007 to 2019, in face value terms. According to a 2021 report by the Advocata Institute, Sri Lanka’s ISBs were issued at high coupon rates (often between 5-8 percent), with some 36 percent of these ISBs being subject to classic collective action clauses, which make restructuring much harder for debtor governments. As a result of this debt-fueled growth strategy (or lack thereof), the country’s ratio of public external debt stock to GDP grew from 29 percent in 2010 to 44 percent in 2021.

The ISB Debt Trap

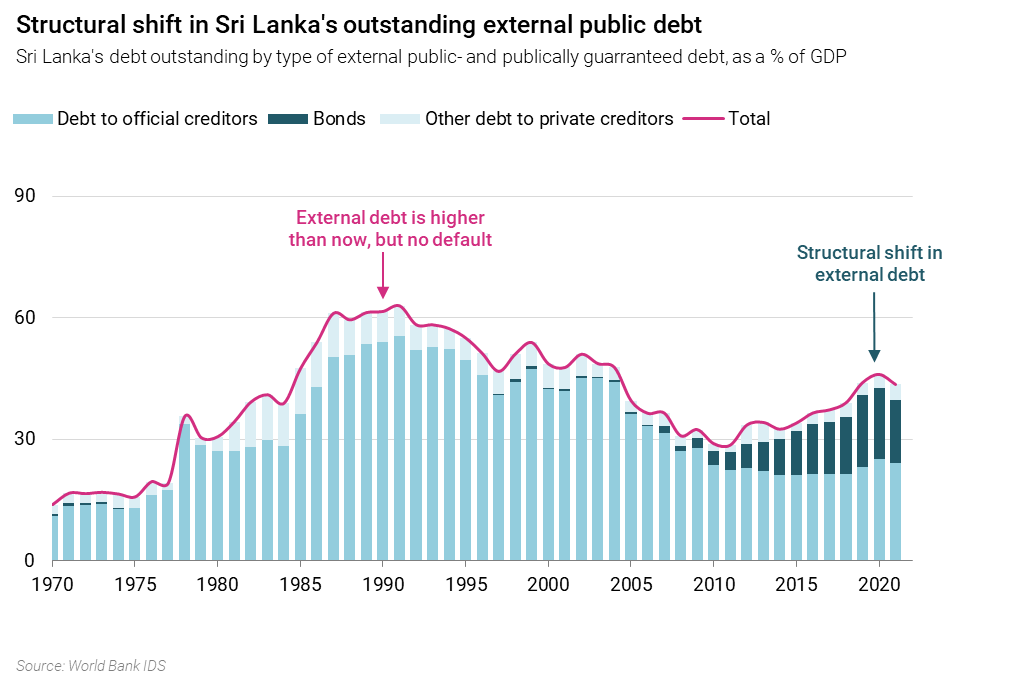

In historic terms, Sri Lanka’s current external debt ratio is hardly a precedent. The country endured higher external debt burdens, crossing 60 percent of GDP, in the 1990s, but managed to avoid a total default. The difference between now and then is that a greater share of the country’s external debt is borrowed from international capital markets at high interest rates.

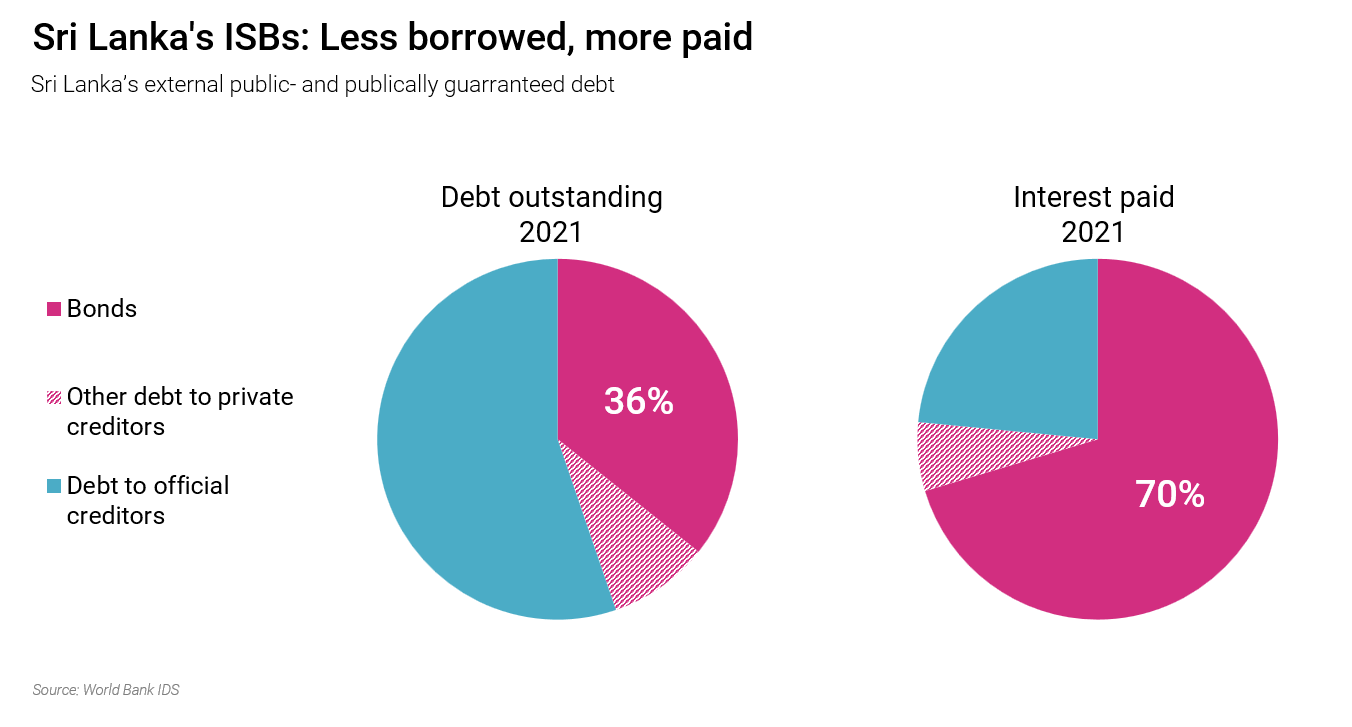

From 2010 to 2021, the ISB share of Sri Lanka’s external debt stock tripled, going from 12 percent to 36 percent. Yet in 2021, ISBs accounted for a monster 70 percent of the government’s annual interest payments. These figures highlight the extent to which high interest borrowing from international capital markets can eat into the foreign currency cash flows of a country, especially when it is wracked by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and conflict in Ukraine.

For underdeveloped countries like Sri Lanka, borrowing from international capital markets is exceptionally risky. Typically, ISBs are not linked to projects and therefore do not produce a corresponding asset or economic growth, nor is there much transparency on how governments budget and spend funds accrued from these bonds. The bondholders themselves comprise a diverse set of interests who are difficult to coordinate with to negotiate a restructure. For example, bondholders like Hamilton Reserve have held out and sued the Sri Lankan government.

Additionally, the bonds themselves are tradable and their prices subject to the decisions of credit ratings agencies. When credit ratings agencies downgrade a country, the price of that country’s bonds decreases and its yield rises. Since the yield acts as the benchmark for coupon rates on future bonds, this makes future borrowing more expensive, and can lead to a snowball effect where a country takes on more debt at higher interest rates to pay back outstanding obligations, which were borrowed at lower rates.

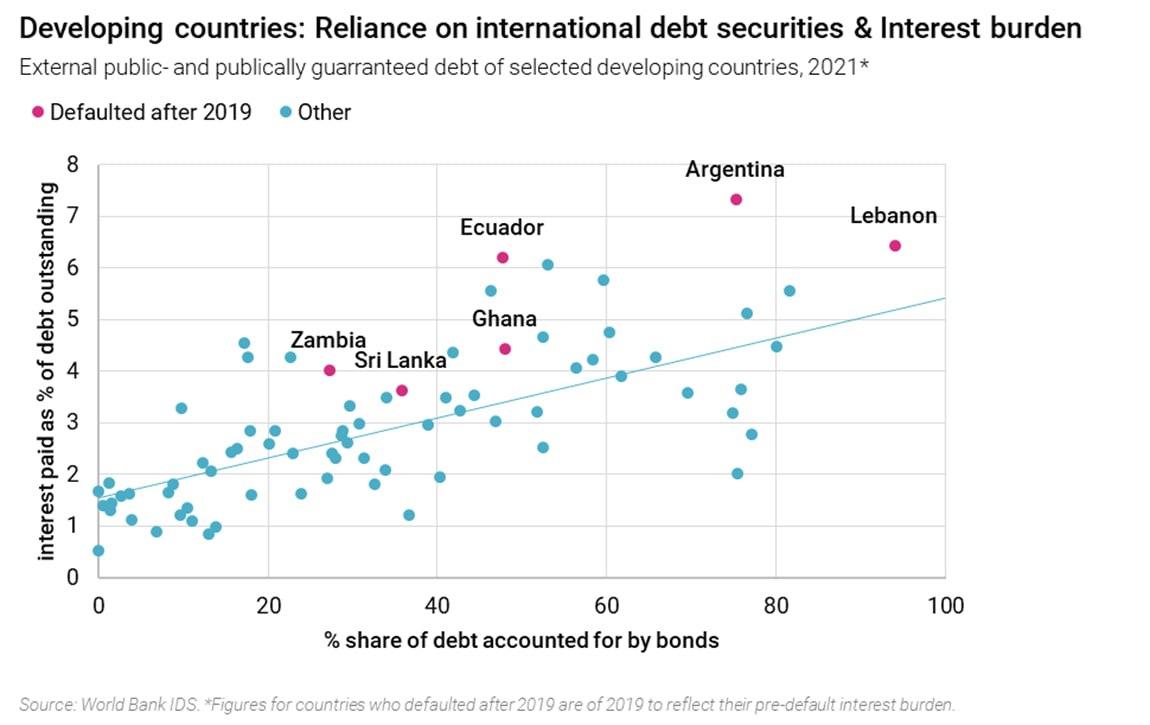

Sri Lanka’s experience is not unique among underdeveloped countries, many of which have fallen for the same ISB debt trap. The allure of low interest rates in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis was seized upon by underdeveloped countries to cover chronic balance of payments issues linked to deteriorating terms of trade from an unindustrialized production base. At the same time, low rates pushed Western institutional investors to seek profits from other sources of income, including the stock market, CDOs, and emerging market debt. The consequences of this shift in debt structure among underdeveloped countries has devastating consequences for citizens who have to bear the brunt of the ongoing debt crisis.

A glance at the composition of total debt stock and debt servicing of underdeveloped countries is telling – the higher the share of ISBs in outstanding debt, the greater the annual interest paid. We find that some of the most debt distressed countries in the world, including those that have defaulted after 2019 – such as Argentina, Lebanon, Ecuador, and Ghana – all have in common a deep exposure to bond markets.

The high level of ISB interest payments tends to exacerbate stresses from external and cyclical shocks, which underdeveloped countries are vulnerable to. For example, the COVID-19 pandemic brought global tourism to come to a virtual standstill in 2020 and 2021, causing Sri Lanka to lose around 24 percent of its annual export revenue. Shortly thereafter, global oil and other commodity prices rose sharply due to the war in Ukraine.

IMF Offers No Solutions

Sri Lanka desperately needs bridge financing to shore up its reserves and ensure a steady supply of essentials such as fuel and fertilizer so that it can resume basic economic activity and restore a sense of normalcy for workers and businesses. As it stands, the country expects to sign its 17th agreement with the IMF in March, nearly a year after negotiations first began. To call the IMF package a bailout would be a misnomer, as the $2.9 billion on offer (to be disbursed in tranches), is scarcely enough to cover Sri Lanka’s annual fuel bill, let alone the $4-5 billion it would normally require for annual debt servicing.

What an IMF agreement will do is restore international creditor confidence and improve the country’s credit ratings. Steps have already been taken to depreciate the currency, increase taxation, implement cost-recovery based pricing for utilities, and privatize state-owned enterprises. Some experts frame this as a positive and an end in itself, as it would help Sri Lanka regain access to international capital markets.

However, taking on more debt from international capital markets is the last thing Sri Lanka needs if it is to find a way out of its debt problem, as this would simply contribute to a snowballing of ISB debt. A good example of this is the case of Egypt, which secured an IMF deal in December 2022 and now plans to issue sukuk (Islamic bonds) at a yield of 11 percent to pay off an outstanding Eurobond, which carries a fixed interest rate of 5.557 percent.

This pattern of going to the IMF and then relying on ISBs for external financing was already tried by the Sri Lankan government from 2016 to 2019, during the country’s 16th IMF program. At the time, Sri Lanka had entered into a three-year extended arrangement with the IMF for a paltry $1.5 billion. Using the “credibility” gained from this arrangement, Sri Lanka issued around $12 billion in sovereign bonds (around 70 percent of the face value of total bonds issued in the country’s history). This was done on the justification that these funds were needed to refinance bilateral project loans. As the data on structure of outstanding debt and interest payments bears out, this refinancing strategy has been disastrous for Sri Lanka, making its annual interest repayment bill higher than it would have been had it stuck with bilateral loans.

Sri Lanka’s long-term prospects for recovery will require a paradigm shift from what it has done up to now. One of the country’s immediate goals should be to deleverage from ISBs exposure, and be more strategic about the kinds of debts it takes on. In the medium to short term, bilateral borrowing remains the country’s safest and most reliable method for financing its external commitments. Curiously, recent revelations by local media suggest that Sri Lanka’s finance minister had secured bilateral financing from China to avoid defaulting in the first place, but was blocked from pursuing this path for political (likely geopolitical) reasons.

This is not to say that Sri Lanka should go to bilateral partners with a begging bowl or accept unsolicited project proposals without due diligence. Rather, the country must take its fate in its own hands and formulate its own industrial development strategy, in which bilateral partners can play a constructive and supportive role. In a sense, this would mean tackling the root cause of Sri Lanka’s debt itself – the massive and protracted trade deficit.