Communists are taught to be terrified of history repeating itself. Apparatchiks fret over their “Eighteenth Brumaire,” the moment when Napoleon Bonaparte seized power and announced the French Revolution was over — and the episode employed by Karl Marx for the title of his essay from which we derive his overused aphorism about history’s tragic, then farcical recital. For Leon Trotsky, it was another repetition that terrified him. Josef Stalin’s assumption of power in 1922, he intoned, was the Soviet Union’s “Thermidor reaction,” another hark back to the French Revolution. At that moment, Trotsky said, revolutions are betrayed.

Twenty-first-century communists have another historical threat. Who will be the “Gorbachev” of the Chinese or Vietnamese communist parties? In the Western mind, a comparison to Mikhail Gorbachev, the general secretary who inadvertently led to the Soviet Union’s implosion, might seem like a compliment. But talking to the New York Times last year after Gorbachev’s death at the age of 91, the political historian Kerry Brown said that China’s leaders “would regard everything the final leader of the Communist Party of the U.S.S.R. did as a textbook of how not to go about business.” Ditto in Vietnam.

It’s beyond the scope of this column to explore in detail, and it remains debated by historians, but one line of thinking contests the idea that the Soviet Union’s collapse was inevitable. Its economy was failing but it could have lingered on for decades. What finished off the communist empire was, first, the Soviet leader’s policy of nonintervention. Leonid Brezhnev, Gorbachev’s predecessor bar two, had already renounced his own eponymous doctrine by not crushing Polish trade unions in 1981. Instead of cracking down on protests in Eastern Europe in the late 1980s, general secretary Gorbachev did nothing.

As such, the Soviet Union collapsed from its peripheries inwards, from the socialist bloc in Eastern Europe to the nationalist claims of the Baltics and Ukraine and the Caucasus. It’s not difficult to see the Chinese government’s tyranny in its peripheries – in Xinjiang, Hong Kong and, potentially, Taiwan – as an attempt to prevent another communist empire from decaying from the edges first.

Second, Gorbachev’s commitment to “reform socialism” meant he was opposed to any tactics employed by those predecessors whose style he was reforming against. (For Gorbachev, that meant Stalin.) In one sense, Gorbachev was reacting as much against history as to contemporary events. Had Gorbachev resorted to Stalinesque terror perhaps the Soviet Union would have endured. “You can’t be half communist,” argues Stephen Kotkin, a Princeton University historian and biographer of Joseph Stalin. “Either you have a monopoly on power or you don’t.”

Among its membership, the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) has a tendency known as the “red flag” nationalists, named after the country’s starred scarlet banner. Active mostly online, they argue that the Party has been too lenient on liberals, has given up on socialism, has become too capitalist, and often dishonors the Party’s heroes like Ho Chi Minh by forging closer relations with America, the group’s bete noire. And they’re on the lookout for a possible Gorbachev figure.

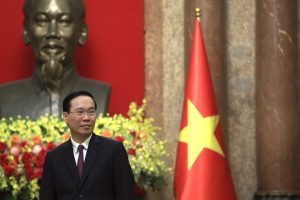

According to some in this movement, that could be Vo Van Thuong, the country’s new state president. On March 2, at an extraordinary session of the National Assembly, legislators confirmed Thuong as president, the day after the CPV nominated him as the sole candidate. He will “strive to fulfill to the best of my abilities the responsibilities and missions entrusted by the party, state, and the people,” he said in his inauguration address, and vowed “to constantly study and follow President Ho Chi Minh’s ideology, morality, and lifestyle.”

That’s par for the course for communist leaders. But give ear to what he then apparently said. “From all over the country,” he added, “I had once witnessed many workers abandoning [the party and communist ideology] when all the socialist countries in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union collapsed, and thereafter gradually became more deeply aware of the importance of loyalty and steadfastness for the goals of the deals and path of the nation that the party, Uncle Ho, and the people have chosen.” One pundit observed that this might have been the first time a Vietnamese leader, in their inauguration speech, referenced the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Thuong as a Gorbachev figure is nonsense, however. Gorbachev was party chief in the Soviet Union, a position cloaked in such authority that few could resist the path he was taking his empire down, including the plotters of a laughable coup attempt against him. Thuong, meanwhile, holds a mainly ceremonial role. He’s a committed party man. He’s clearly trusted by Nguyen Phu Trong, the three-term party chief whose entire career is about restoring the power of the Party over the state and the government.

If one was really looking for a Gorbachev figure in Vietnam, you would have to say that it was Nguyen Tan Dung, the former prime minister who was crushed by Trong in 2016. The individualist reformer, who more closely resembled an autocratic leader from a non-communist state, was driven out of power by a man who feared that Dung was overseeing the withering away of the Party’s role in all areas of social life. The analyst Carl Thayer once described Dung as “an individualist working within a conservative system of collective leadership.”

It’s tempting to imagine what would have happened had Dung become party chief in 2016 instead of Trong. There would have been no “burning furnace” anti-corruption drive that has refashioned the party into the image of Trong, an ideologue and prude – and, indeed, someone who has fostered a puritanical streak that harks back to the Party’s leaner beginnings. There would likely have been an even closer relationship with Western democracies, perhaps at the expense of the Party’s own internal power. The private sector would have had more independence and authority than it does today, posing a threat to the Party’s monopoly. Instead, Trong, now in his probable last term as general secretary, has done more than any of his immediate predecessors to put socialism and ethics –and, indeed, socialist ethics, as he sees it — at the center of Party relations. In that mold we find Thuong.

All that said, the fact that a tendency of the Party faithful is still awaiting the arrival of a Gorbachev figure with trepidation (and, indeed, some fatalism) indicates a deep unease about the stability of the communist system. In Party lingo, there are two primary threats. “Peaceful evolution” refers to attempts by outside powers to foment regime changes. A general at the Ministry of National Defense’s Political Academy, writing in the National Defense Journal in 2018, put it in a matter-of-fact way: “Hostile forces have been employing malicious artifices to consistently and vigorously oppose the Vietnamese revolution to topple Communist Party of Vietnam’s leadership, and subsequently removing Vietnamese socialist regime.”

The second and corollary threat, to some, is “self-evolution” or “self-transformation,” a claim that forces are consciously trying to dismantle the regime from within. That theory, though, stands at odds with reality. Fear of “self-evolution” or “peace evolution” are so ingrained in generations of cadres and theoreticians that the powerful are always on the lookout for an official who may be suspect. Also, it would require an entire “generation of pro-Western cadres” to rise to the very top of the Party to destroy it from within.

But the accusers tend to suggest this is a bottom-up process. “A number of cadres and party members become disoriented and skeptical about the leadership of the Party, the goals, ideal[s] and the path to socialism in Vietnam,” reported another essay from the National Defense Journal. It went on: “When [the] political ideology of a number of cadres and party members is degraded or disoriented, the political system may be weakened, separated or even collapsed.” If one wants to understand what Trong’s three-term tenure as party chief is about, that last sentence is an adequate summation.

The “Gorbachev threat” points to something different, though. Gorbachev never intended to collapse the Soviet Union. He was no “pro-Western cadre” journeying down the path of “self-transformation”. Instead, he was misguided (if one is looking through party eyes) in the belief that one can have economic and political reform at the very same moment. For committed ideologies, Gorbachev is a reminder of the one actual law of history, that of unintended consequences.