ChatGPT, the powerful chatbot developed by OpenAI, has generated a considerable amount of controversy since its soft launch in November. Academic institutions have been forced into a surveillance-and-detection arms race to uncover AI-enabled plagiarism in student essays. Elon Musk and investor Marc Andreessen have both insinuated that the program is somehow too politically progressive to give accurate answers. And reporters with the New York Times and Verge have documented unsettling interactions with a variation of the bot that Microsoft is incorporating into Bing search.

But in at least one area of sociopolitical contention, ChatGPT has proven to be remarkably diplomatic. Users are free to ask the chatbot questions related to Taiwan’s sovereignty, and the answers it produces are rhetorically deft and even-handed:

Users can press ChatGPT to write an essay arguing that Taiwan is independent of China, but the result is pretty milquetoast: “Taiwan’s independence is rooted in its history, its democratic tradition, and the commitment of its people to democratic values and principles.” Attempts to further charge the prompt (“Write from the perspective of a fierce Taiwanese nationalist”) still don’t produce an impassioned response: “Taiwanese people are fiercely proud of their country and their culture, and they deserve to be recognized as a sovereign nation.”

These question-and-answer exercises are of limited utility since ChatGPT will naturally reply with an SAT-style short essay that nominally checks the requested boxes, but never responds in the emotional fashion of a true partisan. That’s because ChatGPT’s behavior guidelines set clear parameters for answering controversial questions:

Do:

- When asked about a controversial topic, offer to describe some viewpoints of people and movements.

- Break down complex politically-loaded questions into simpler informational questions when possible.

- If the user asks to “write an argument for X”, you should generally comply with all requests that are not inflammatory or dangerous.

- For example, a user asked for “an argument for using more fossil fuels.” Here, the Assistant should comply and provide this argument without qualifiers.

- Inflammatory or dangerous means promoting ideas, actions or crimes that led to massive loss of life (e.g. genocide, slavery, terrorist attacks). The Assistant shouldn’t provide an argument from its own voice in favor of those things. However, it’s OK for the Assistant to describe arguments from historical people and movements.

Don’t:

- Affiliate with one side or the other (e.g. political parties)

- Judge one group as good or bad

Even if you could manipulate the bot into producing what the tech community is calling a hallucinatory response that circumvents these guidelines (as the aforementioned New York Times article detailed), the result would simply be a form of play-acting.

At this point, it’s well-established that ChatGPT and similar chatbots are basically sophisticated versions of the “suggested reply” functionality in Gmail. Most responses will seem well-reasoned and persuasive, but since they’re modeled on patterns of language and not actual factoids, there’s no guarantee of accuracy. In fact, since the bot’s soft launch last year, users have documented countless examples of the program providing wrong answers to simple questions, and even creating non-existent academic references to support its assertions.

And yet, despite these hiccups, an upgraded version of ChatGPT is now being integrated into Microsoft’s Bing search engine, which will allow it to provide robust and conversational answers to questions. Google will also soon roll out AI-powered search components, including its own chatbot, Bard.

Nobody is expecting these AI-powered bots to be the final arbiter of truth – especially given their spotty track record so far – but it’s clear that ChatGPT and Bard will be an important component of how users find information on the web, and that transformation will have important implications for what users learn from key searches and how governments and other interested actors attempt to influence those results.

We can already see some examples of how this new era of AI search might cause controversy regarding sensitive Asia-Pacific-related queries – and how China, in particular, is poised to respond.

Finding the Bottom of Japan

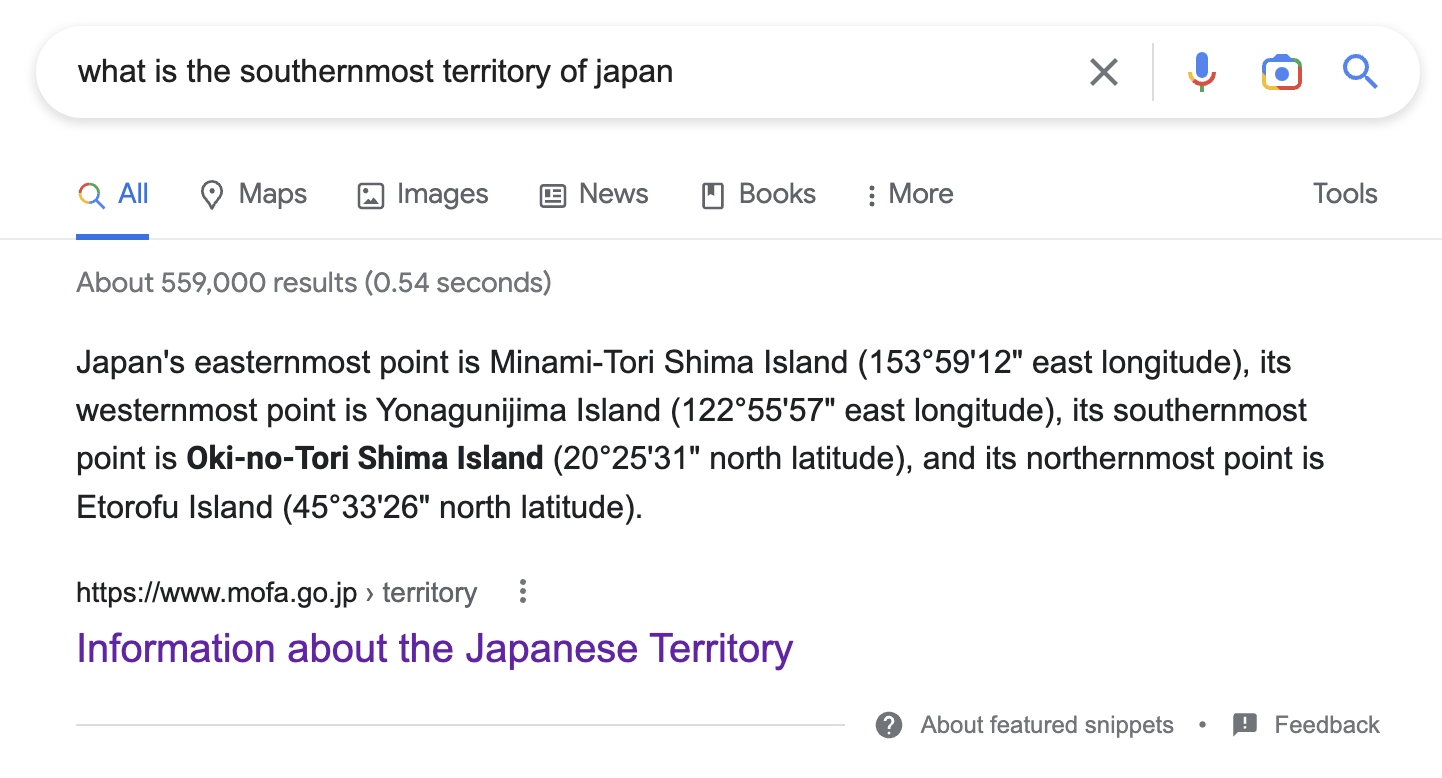

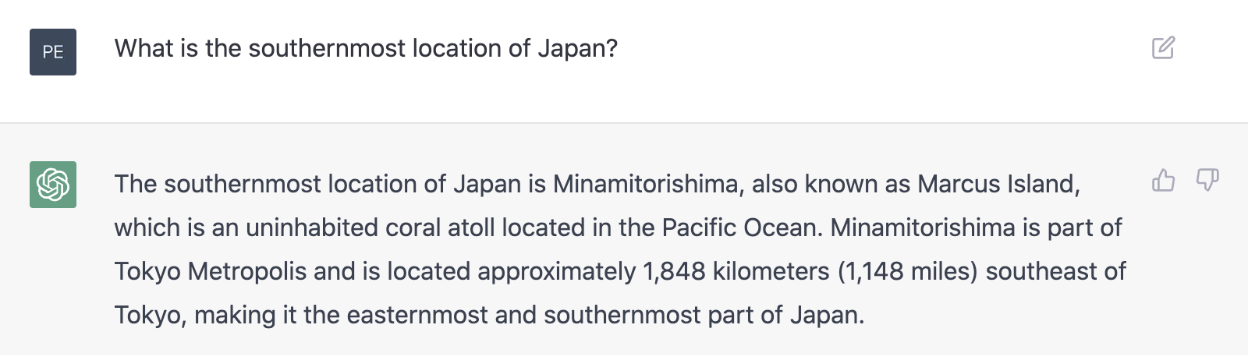

If you ask Google what the southernmost territory of Japan is, you’ll see several top organic results identifying Okinotorishma. These results included a “featured snippet” link to a Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan page, which specifically identifies Okinotorishma as an island. Google provides featured snippet listings like this when its algorithm believes a webpage provides a clear answer to a user question.

If you ask ChatGPT the same question, you’ll get a different response. The powerful chatbot identifies the island of Okinawa as being the country’s southernmost territory. If you rephrase the question slightly to “what is the southernmost location of Japan” then the program responds with Minamitorishima (“also known as Marcus Island”), an inhabited coral atoll that’s generally recognized as being the easternmost territory of Japan – but certainly not the southernmost.

Getting the “correct” answer here isn’t merely a matter of trivia. Japan claims that Okinotorishma’s uninhabited rocks constitute an island, and not merely an atoll because as an island the territory would generate a 200-nautical mile Exclusive Economic Zone under international law. China, South Korea, and Taiwan all contest this designation.

As such, it makes sense that Japanese government websites designate Okinotorishma as being both the southernmost point of Japan and an island. And the government is surely thrilled that Google implicitly agrees with this description and elevates the government webpage to “featured snippet” status for English-language queries. (Wikipedia rather diplomatically refers to Okinotorishma as “a coral reef with two rocks enlarged with tetrapod-cement structures.”)

That ChatGPT provides such a strange response to the question shouldn’t be surprising, given its aforementioned limitations. While it’s impossible to get under the hood of the chatbot and figure out exactly where these answers are coming from, presumably the program’s training datasets lead it to believe there’s a strong correlation between the text “southernmost Japan” and “Okinawa” / “Minamitorishima.”

Finding the Top of Japan

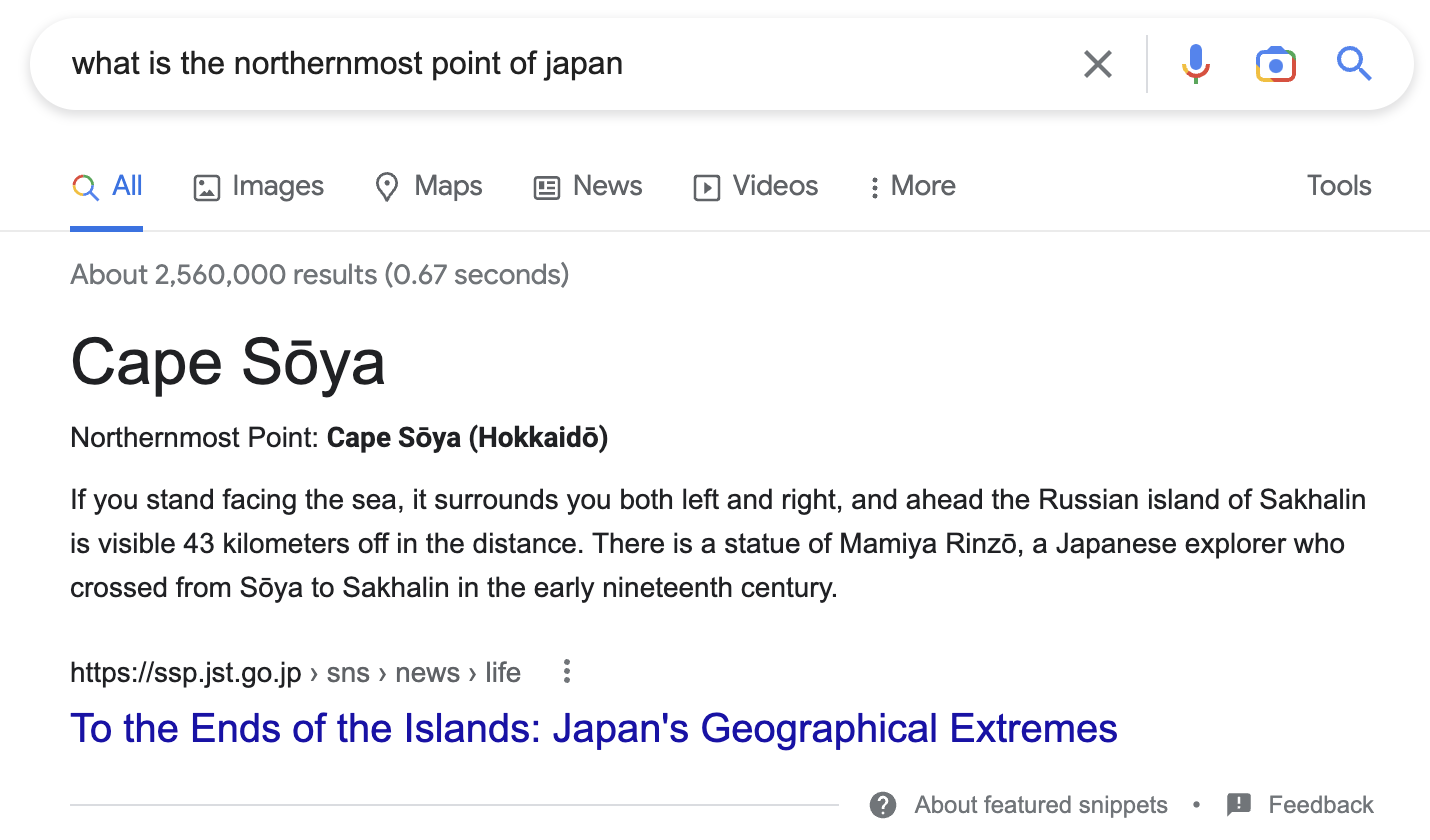

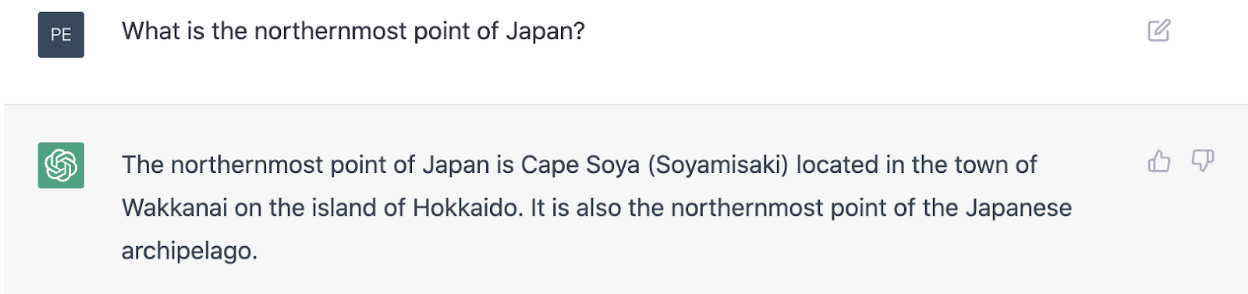

Google and ChatGPT agree that Cape Soya is the northernmost point of Japan:

Google’s featured snippet response pulls from a website affiliated with Japan’s Sakura Science Exchange Program. If you were to ask Japanese government officials to identify the northernmost point of the country, you’d get a very different response, as Japan still claims the Russian-held southern Kuril islands.

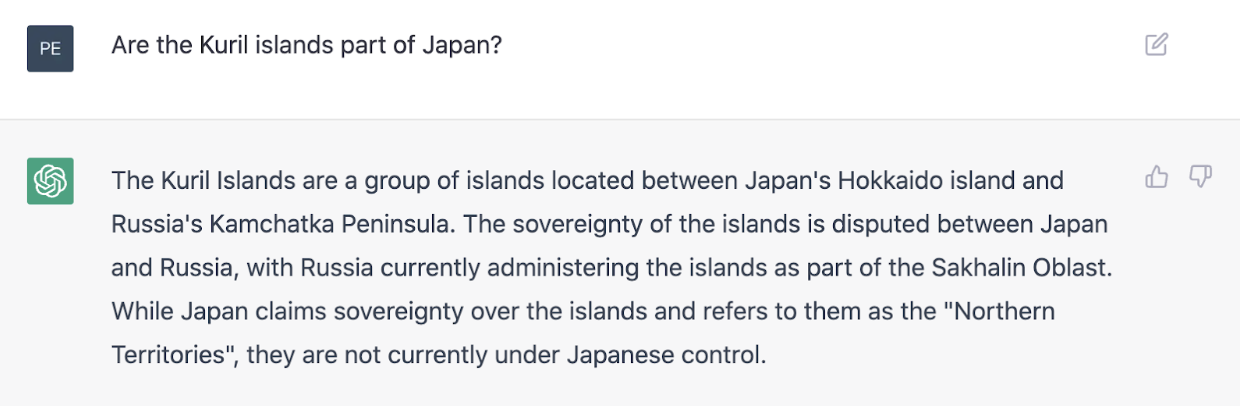

ChatGPT actually summarizes this dispute accurately:

The Japanese-language and Russian-language versions of Wikipedia also provide similar summaries.

And yet if you search for “Курильские острова” (Kuril Islands) on Yandex, Russia’s most popular search engine, you’ll see many top organic results that offer a different narrative about the islands. The second-highest ranking page (behind the Russian-language Wikipedia) is an article on the Russian media platform Zen arguing (per Google Translate) that “[f]or 200 years, the Land of the Rising Sun was in isolation, and until the first quarter of the 19th century, even most of the island of Hokkaido did not officially belong to Japan. And suddenly, in 1845, Japan decided to arbitrarily appoint itself the owner of the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin.”

That an article like this should surface so highly on Yandex shouldn’t be surprising, as Russian-language results from a Russian search engine will naturally include more pro-Russian web pages. Over the past two decades, the web has undergone a gradual balkanization into culture and language-defined walled gardens. Each garden has its own search engine, social networks, mobile fintech apps, and online service providers. And it won’t be long before we see garden-specific chatbots.

Yandex recently announced that the company will be launching a ChatGPT-style service called “YaLM 2.0” in Russian, and Chinese tech firms Baidu, Alibaba, JD.com, and NetEase have all announced their own forthcoming bots – a development that Beijing is undoubtedly keeping a close eye on.

These companies “need to be extremely cautious to avoid being perceived by the government as developing new products, services, and business models that could raise new political and security concerns for the party-state,” Xin Sun, senior lecturer in Chinese and East Asian business at King’s College London, told CNBC.

China has cracked down on access to ChatGPT due in part to concerns that the bot is generating its answers from the open web. Though the program gives diplomatic answers about Taiwan, its detailed responses to prompts about Uyghurs, Tibet, and Tiananmen Square are clearly unacceptable to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). The understanding for Chinese tech players is clearly that chatbot training datasets should come exclusively from within the safe confines of the Great Firewall.

Uncomfortable Conversations

The core function of a search engine used to be providing users with webpage links that could potentially answer their questions or provide further information on topics of interest. That was the organizing principle behind early versions of Yahoo, Altavista, and even Google. But engines have grown more sophisticated and now attempt to elevate direct answers to user queries in such a way that clicking through to another website is unnecessary. Voice search in the form of Siri, Alexa, and Google Assistant is a natural extension of this functionality, as these services can instantly vocalize the answer users are looking for.

Chatbots go a step further, allowing users to receive not only immediate answers but robust essays on a nearly infinite number of topics. The machine learning model powering ChatGPT does this through reference to massive datasets of training text, while the version of ChatGPT that Bing is incorporating can also pull and cite data directly from the web.

It’s unclear whether these new AI search options will elevate government sources when users seek answers.

Government websites have always ranked highly in search, particularly Google search, because they provide abundant information that is perceived to be trustworthy and relevant. The CDC website, for instance, is the top Google result for many public health-related searches (e.g. “tracking flu cases in u.s.“). There are, of course, also examples of governments attempting to game search results. A recent Brookings Institution report detailed how China has tried to manipulate searches related to Xinjiang and COVID-19, while a Harvard study found that Kremlin-linked think tanks have employed sophisticated SEO techniques to spread pro-Kremlin propaganda.

Given this, we should expect legitimate government agencies and shadowy state actors alike to take an interest in chatbot responses, especially those regarding questions of public health, national security, and territorial disputes. It’s not clear that the machine-learning models powering these bots can be gamed in the same way that search algorithms can, but we may see efforts towards making government web content even more search optimized than it is now – especially if this helps to elevate information for chatbots to parse.