Prime Minister Chris Hipkins is blazing his way through New Zealand’s foreign policy. His fast-but-furious visit to Papua New Guinea this week – which saw Hipkins spend just 23 hours in Port Moresby, the capital – was the prime minister’s fourth such rapid international trip since he took office.

But after two quick visits to Australia and one to the United Kingdom, this was Hipkins’ first foray into the Pacific.

Moreover, Monday’s trip to Papua New Guinea put Hipkins at the heart of the new “Great Game” for control of the Pacific. And in the geopolitical battle between the United States and China, New Zealand is increasingly being asked to pick a side.

Hipkins responded to yet another new superpower security deal – this time between the United States and Papua New Guinea – by saying that New Zealand did not support the “militarization of the Pacific.”

At first blush, this might seem like a surprising criticism of the United States, an increasingly close partner of New Zealand. But Hipkins went on to argue rather unconvincingly that “having a military presence doesn’t necessarily signify militarization.” Effectively, this was Hipkins giving Wellington’s green light to Washington’s new pact.

For its part, Beijing has already sharply criticized the Papua New Guinea-U.S. defense pact as “geopolitical games.”

To some extent, Hipkins’ linguistic gymnastics are only to be expected, given New Zealand’s gradually more U.S.-friendly approach to foreign policy that has unfolded under the leadership of both Hipkins and his immediate predecessor, Jacinda Ardern.

However, ambiguity remains over just how far this new approach will go.

Of late, Hipkins has been dialing down expectations set by his defense minister, Andrew Little, that New Zealand is considering joining the “second pillar” of the AUKUS defense partnership. These currently link Australia, the United Kingdom, and United States, but other partners are being sought.

In response to media questioning on New Zealand’s potential role in AUKUS on Monday, Hipkins would only say “that’s not clear.”

But it can be assumed that U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken privately put some AUKUS pressure on New Zealand when he met with Hipkins on the sidelines of the summit in Papua New Guinea.

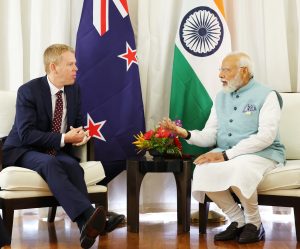

Another major highlight of Hipkins’ one-day mission to Port Moresby was a chance for his first meeting with Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India.

Positively, Modi tweeted of an “excellent meeting” with Hipkins, adding that the pair had discussed “how to improve cultural and commercial linkages.”

Wellington has playing catch-up in its relationship with New Delhi ever since India’s external affairs minister, Dr. Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, was the subject of a rather underwhelming reception during his visit to New Zealand in October last year. In response to the criticism, Nanaia Mahuta, New Zealand’s foreign minister, flew to India in February for her first overseas trip of 2023.

In the meantime, a pledge by Hipkins’ main political rival – opposition National Party leader Christopher Luxon – to make the relationship with India a priority has probably also focused minds in Hipkins’ Labor Government.

While any progress is to be welcomed, New Zealand still lags far behind its bigger neighbor when it comes to ties with India. Following his stop in Port Moresby, Modi is heading to Australia for talks with his counterpart, Anthony Albanese, and a sell-out address to 20,000 people at Sydney’s Olympic Park.

Although Ardern issued a public invitation for Modi to visit New Zealand, the Indian prime minister has made no plans for a side-trip to Wellington while on his rare visit Down Under.

If Hipkins needed any further encouragement of India’s importance, he needed only to listen to James Marape, Papua New Guinea’s prime minister.

On Monday, Marape was effusive in his praise of Modi during his counterpart’s visit to Papua New Guinea, describing him as “the leader of the Global South.” Calling on Modi to continue to speak up for countries such as Papua New Guinea in meetings with superpowers, Marape vividly depicted developing countries as the “victims of global power play.”

Above all, Modi’s presence was a reminder that Port Moresby has options.

The remarks by Marape will be a salutary lesson for some of the bigger Pacific players. Countries such as Papua New Guinea expect to be treated with genuine respect and interest, rather than as mere geopolitical pawns.

Indeed, Marape’s comments contrasted starkly with the ostensibly inclusive, yet ultimately exclusionary “Pacific family” language that Canberra and Wellington have frequently deployed over the past year.

To be fair, New Zealand has been putting in some effort with Papua New Guinea, despite its location in Melanesia, farther away from New Zealand’s traditional Polynesian heartland. Well before Hipkins headed to Port Moresby, Mahuta made a special trip to Papua New Guinea in September last year.

That visit came in the context of the Pacific travel push by Western leaders following the China-Solomon Islands security deal signed in early 2022. But other efforts predate that sense of urgency. New Zealand and Papua New Guinea signed a Statement of Partnership in 2021, and Marape visited Wellington just prior to coronavirus lockdowns in February 2020.

The recent appointment of Peter Zwart as New Zealand’s new High Commissioner to Papua New Guinea provides further justification for some optimism. The job is Zwart’s first ambassadorial-level position, but Wellington’s new man in Port Moresby brings a strong track record in Pacific development. He has also previously been posted to China. Prior to becoming a diplomat, Zwart was the international program manager for the New Zealand arm of Catholic aid agency Caritas. In the current geopolitical context, Zwart will need to draw upon all of his previous experience while representing New Zealand’s interests.

Whatever happens, Port Moresby will remain a key regional capital on Wellington’s radar.

Chris Hipkins has now had his first taste of the Pacific as New Zealand’s prime minister. With under 24 hours on the ground, it was the definition of a flying visit. But it was just the beginning.

This article was originally published by the Democracy Project, which aims to enhance New Zealand’s democracy and public life by promoting critical thinking, analysis, debate, and engagement in politics and society.