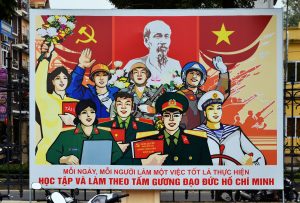

Although the United States and Vietnam are ideologically different, recent bilateral developments show that both countries are now more open to direct exchanges between the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV) and the U.S. government. Beyond the historic visit of CPV chief Nguyen Phu Trong’ to the White House in 2015, U.S. officials increasingly engage with lower-level CPV cadres. Recent examples include Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s meeting last month with Le Hoai Trung, the chair of the Central Committee’s Commission for External Relations, and U.S. Ambassador Marc Knapper’s dialogue with Ho Chi Minh City CPV chief Nguyen Van Nen in April.

Such a shift reflects the U.S. respect for the CPV’s political authority and the Biden administration’s avowed willingness to “partner with any nation” that supports the “rules-based order.” The U.S. accommodation of the CPV’s internal security is not an aberration. U.S. foreign policy has traditionally downplayed ideological differences with important security partners.

Despite the U.S. and Vietnam working to overcome their political differences, some Vietnam watchers have expressed skepticism about this idea, suggesting that Vietnam was “playing” the U.S. and would kowtow to China because it needed Chinese political support to ensure the continuation of CPV rule. Other watchers go even further, suggesting that the CPV would sacrifice “national interests” out of ideological “deference” to China.

The ideology argument is straightforward: because Vietnam and China share the same ideology – market-inflected communism – the CPV would prioritize its political survival and Chinese support thereof over its sovereignty in the South China Sea. It is thus not possible that Vietnam would confront its Chinese ideological supporter. But is Vietnam’s foreign policy completely driven by ideology? A thorough examination of the ideology argument would expose its methodological weaknesses and its ignorance of political reality.

The ideology argument starts with an assumption that the CPV’s only goal is political survival, and that only China can provide the support necessary to help the CPV succeed. This assumption originated at the end of the Cold War, when Vietnam had seemingly to reach a consensus with China to ensure the continuation of CPV rule as the Soviet bloc collapsed. The CPV was interested in forging an ideological alliance with China, a proposal that China rejected because Vietnam and China were “comrades, not allies.” It is not surprising that the CPV’s ideological rapprochement with China gave the impression that the CPV needs China’s support to survive. However, there are several problems with this assumption.

First, it is too narrow. The CPV can ensure its political survival by many other means besides Chinese political support. The CPV’s performance legitimacy means that it must defend its territorial integrity, ensure economic development, crackdown on corruption, and avoid international isolation. In other words, the CPV must defend the state as much as it defends the party, or else its own political power would suffer from a lack of popular support. As a party-state, the survival of the party cannot be detached from the survival of the state. Importantly, it is questionable why the CPV needs Chinese political support to survive. Other scholars noted that the longevity of the CPV does not rest on China’s political backing but on the CPV’s own strong party-state institutions forged by its successful resistance against both external and internal anti-party elements since 1945.

Second, the assumption is reductionist. By assuming that the CPV only wants political survival at the expense of all other goals, it takes political survival out of a bigger historical context and paints the picture of a CPV always worrying about its internal security, while that is not the case most of the time. Vietnam is proud of its political stability and absence of terrorist attacks. The CPV’s goals are better described as contingent, meaning that they have varied in different historical periods. Before a consolidation of the communist regime in North Vietnam in 1954, the CPV certainly worried about its political survival. However, once it achieved such a goal thanks to the international recognition of the communist government under the 1954 Geneva Accords, the CPV wanted to reunify Vietnam under its rule. The CPV did not have to reunify the country just to ensure its political survival because it faced little domestic resistance in the North, and a South Vietnamese “march North” was unlikely due to the U.S. restraint of the Saigon government.

After the Vietnam War, the CPV wanted to rebuild the national economy, assert its territorial claims against China, and protect its southern border against the Khmer Rouge. In the modern era, the CPV’s goal is to maintain internal and external stability in service of economic development, meaning it is open to befriending all countries regardless of their ideologies. Had the CPV considered political survival the only goal, it would not have downplayed ideology in its foreign policy after the Cold War, or potentially adopted North Korea’s hermitic methods of political survival to protect itself from foreign influence. The main point is that while political survival is important, the CPV wants more than mere political survival, and ignoring its other goals would fail to fully explain Vietnam’s foreign policy.

Because the assumption is too restrictive, ideology-only explanations derived from this assumption either downplay major historical evidence that does not conform with the theoretical outcomes or commit a predictive fallacy in order to remain logically coherent. By arguing that Vietnam would not confront China because of a shared ideology, these watchers could not explain why the CPV was determined to resist China at great cost during the 1970s and 1980s. It is not a coincidence that anti-CPV writers tend to ignore the history of Vietnam’s resistance against China during these years because such a historical period poses challenges for their ideology argument. Ideology arguments are also oblivious to the power political origin of Vietnam’s rapprochement with China in 1991. Vietnam had to come to terms with China not solely because of a shared ideology, but because it no longer had the Soviet Union as a reliable patron and the costs of Chinese coercion were too great to bear.

Moreover, by treating ideology as a stand-alone independent variable, these analysts come to an inevitable prediction that Vietnam will not confront China in the future. Then, they try to explain Vietnam’s current behavior as an attempt to con the U.S. by pointing to that prediction as an explanation, which completely reverses the natural causal chain of events. Importantly, the prediction is a fallacy because it ignores other variables that directly affect China-Vietnam relations, such as China’s coercion of Vietnam at sea, or Vietnam’s defense relations with extra-regional great powers. It is impossible to predict what will happen in the future for variables interacting with each other can result in completely different unpredictable outcomes from when they operate alone. In short, the ideology variable alone is insufficient to explain Vietnam’s foreign policy.

Any serious attempts to understand Vietnam’s foreign policy should start with analytical modesty, namely, that there are limits to what the theories can explain or even predict. Contrary to the ideology argument, ideology itself is not an independent variable, but an interdependent variable alongside the variable of power politics. The complex and holistic nature of politics means that watchers should be aware of the limitations of relying on a single variable to explain any outcomes. The fact that Vietnam shares an ideology with China says little about the trajectory of the bilateral relationship; the two countries have remained communist for more than 70 years but have experienced ups and downs in their bilateral relations during that time.

Likewise, power politics alone is not sufficient to understand Vietnam’s behavior. Vietnam’s domestic politics can shape how it sees friends and foes, which a simple balance-of-power perspective cannot capture. Just because the U.S. and Vietnam share some security interests does not automatically mean that they will be allies. Vietnam’s 2019 Defense White Paper says clearly that “depending on the circumstances and specific conditions, Vietnam will consider developing necessary, appropriate defense and military relations with other countries.” Vietnam’s foreign policy choices are again contingent, not predetermined.

Theory is after all a means to explain reality, not to distort it. Vietnam watchers are better off explaining less with more, instead of more with less, at the expense of historical accuracy.