The Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) had its electoral baptism during the general election of May 2022, when it fielded candidates at the municipal level for the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM) in the southern Philippines. The former rebel group learned a hard lesson that its newly created political party, the United Bangsamoro Justice Party (UBJP), has a severe handicap in relation to the traditional politicians who are entrenched across much of the region. After being handed the reins of the transitional authority in the interim parliament of BARMM, it will need to rethink its strategy and approach, if it wants to hold on to power. Some stakeholders in the region have even gone so far as to assert that a UBJP failure in future elections puts at risk the long-term peace and stability in the region.

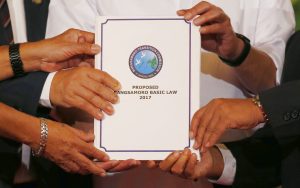

Since 2019, the BARMM has been in a state of transition. The autonomous region was created as a result of a negotiated settlement after decades of armed struggle between the Philippine government and MILF, which sought self-determination for the Bangsamoro people in the southern Philippines. While the MILF currently helms this interim government, it is obliged to hold regional elections in 2025 for the BARMM parliament to demarcate the end of the transition period. However, their path to victory in the 2025 election is anything but assured. In order to win the parliament, they will need to first win at the grassroots. With the barangay elections coming in October, the MILF is in a race against time to mobilize its base.

In their inaugural electoral test, not only did the UBJP lose in areas previously thought to be MILF strongholds, but also the MILF’s own membership broke ranks and voted against UBJP-backed candidates. The elections were also marred by reports of widespread electoral violence. Despite the existing peace agreement, high hopes for a permanent resolution to the southern Philippine conflict, violence fatigue, and strong feelings of resentment between contesting parties continue to fester and drive the common use of violence during electoral competition. Almost a year after the closing of the polls, in the municipality of Datu Odin Sinsuat in Maguindanao del Norte, streamers all over the city still call for justice for Datu Jamael Sinsuat, a UBJP-backed mayoral candidate who was gunned down as he emerged from Friday prayers on September 30, 2022.

“Since the start of the transition period, we are seeing more horizontal violence in the region,” reported a former member of parliament for the Bangsamoro Transition Authority (BTA). Multiple stakeholders share similar concerns of horizontal or intracommunal violence spreading across the BARMM, particularly across central Mindanao. The director of a non-governmental organization monitoring disaster risk in the region similarly stated that “although the vertical conflict between the rebels and the government have largely subsided, the violence is now horizontal within the communities.” What lies at the heart of this uptick in violence? “Land and political office,” the director stated.

Since taking office last year, Vice President Sara Duterte has on multiple occasions visited Pikit, a municipality particularly embroiled in cycles of horizontal violence, in an attempt to quell the “climate of fear.” Yet, competing political actors continue to point the finger at each other as the root cause of the problem. Traditional political clans and their allies are blaming the MILF for delays in decommissioning their combatants, as outlined in the Normalization Annex of the Comprehensive Agreement of the Bangsamoro. Meanwhile, the MILF attributes the violence to the proliferation of private armed groups working on behalf of the incumbent political clans, claiming that most of the victims of political violence are, in fact, UBJP-backed personnel.

The maintenance of peace in the BARMM is fragile and the 2025 parliamentary elections loom large. A recent International Crisis Group report indicated that these elections will be “the real test of the Bangsamoro’s durability as an autonomous region.” Speaking to observers on the ground, the embattled MILF and UBJP have two simultaneous paths to victory: from top-down, receiving the endorsement of Malacañang over the traditional political clans; and from the bottom up, building support and coalition at the grassroots level to draw support away from the established incumbent politicians. Both paths are mutually reinforcing: getting the support of President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. means that the MILF will also have to deliver the votes for his allies in Congress, and to do so, they must be able to sway the vote among their constituencies. But can they get there?

In April, Marcos offered the strongest indication yet that Malacañang is ready to throw its weight behind the UBJP. He surprised many by appointing as governor of Maguindanao del Norte Abdulroaf Macacua, the chief of staff of the MILF armed wing. This appointment, supported by the then secretaries of the Department of National Defense and the Office of the Presidential Adviser on Peace, Reconciliation, and Unity further signified a clear warming between President Marcos Jr. and the MILF. But while the MILF may have been able to out-maneuver the traditional politicians at the top level, influential political clans are fiercely defending their turf at the grassroots.

The former governor of Maguindanao del Norte, Fatima Ainee Sinsuat, disputed the legitimacy of Macacua’s appointment and enlisted the support of her long-time ally, Mariam Mangudadatu, governor of the neighboring Maguindanao del Sur, in rejecting it. The Mangudadatus, as many local political insiders conveyed, are widely believed to be the kingmakers of the region, and the MILF’s biggest obstacle to the top job of chief minister of the BARMM in the 2025 parliamentary elections.

So, what makes the barangay elections so important? The outcome of these elections in October will set off the first electoral domino that could determine the future of the BARMM. The Philippines’ Local Government Code, passed in 1991, gives local governments a high level of autonomy, including a large share of national revenue through the Internal Revenue Allotment. Even if the MILF/UBJP holds interim power over the BARMM, they must contend with the local governments’ high degree of independence from them. In fact, many MILF MPs in the transitional government have openly expressed their frustration that local government officials actively thwart their efforts at governance and regional development.

But most importantly, the Sangguniang Barangay (barangay council), and barangay captains in particular, hold tremendous influence over the voting behavior of their constituents. They act as de facto gatekeepers between the electorate and the broader political system, from dispute resolution of civil matters to the distribution of financial resources to the community. Members of the Sangguniang Barangay have intimate knowledge of their communities and often exercise tight controls to ensure incumbency by doling out favorable judgments or withholding scarce resources. As the executive director of a local civil society organization explained, this gatekeeping effect is especially pronounced in the BARMM, where poverty levels were once the highest in the country. Barangay captains control much of the disbursement of the few funds available, such as the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino program, the national anti-poverty strategy. Consequently, “communities in the BARMM simply do not vote against what their leaders tell them,” he explained.

The political stakes are therefore high in the BARMM’s barangays. Traditional political clans typically pack the Sangguniang Barangay with their own supporters. Even superintendents and elementary school principals become important political actors as they oversee the polling sites and voting centers, which can decisively swing (or rig) an election. With the competition for control now extending to the MILF, there are potential cracks in the organization’s cohesion and unity. Rumors already abound that local politicians are buying off MILF commanders and members on the ground, capitalizing on delays in the normalization process. Some of these dynamics are contributing to episodic violent clashes and infighting amongst the MILF’s own base commands.

Controlling the barangays is largely seen as a crucial step toward enhancing control of scarce financial resources to local communities and potential electoral influence in 2025. How the UBJP performs in the upcoming barangay elections will depend on how well it can navigate divisions among its followers and fierce competition with traditional politicians. Furthermore, the UBJP faces one big challenge that its traditional political counterparts will not – the high expectations that they will deliver on the promises of the peace agreement for the communities in the BARMM.

Although campaigning for the upcoming barangay elections has not yet begun, the violence is already underway. Between January and April, at least 13 elected officials were victims of targeted killings. These were considered direct effects of the new competition, in addition to the already rampant instances of rido (clan feuding) and land conflicts. The violence is only expected to rise as campaigning ramps up in the coming months. For the MILF and UBJP, the key will be to strategically field their candidates, understanding where they have the strongest support and where they can forge coalitions and make the deals necessary to put them in the best position for 2025.

The standoff between the former rebels and the established political clans, therefore, has the potential to become a powder keg. “If the peace process cannot stay on track, then 2025 will be a bloodbath” considered a source closely involved with the process. The 2025 election for the new BARMM parliament and the government will be a key inflection point for the future of the region. The forthcoming barangay elections are a litmus test that could potentially tilt the balance in favor of the UBJP and provide momentum toward victory in 2025. But its failure, or an outbreak of post-election violence, might be a bad omen for the prospects of peace and stability in the BARMM.