Uzbekistan is not the first country that comes to mind when talking about renewable energy. But the gas-dependent nation with extensive fossil fuel reserves and a decaying network of Soviet-era transmission infrastructure is making strides toward unlocking its potential for wind and solar power and outpacing its neighbors in the process.

Amidst the energy and electricity crisis, the pursuit of renewables is as much about addressing the threat of climate change as it is about shoring up its energy security. Uzbekistan is appearing to take steps away from Russian energy imports and uncertainties in trading electricity regionally and moving toward new partners, particularly in the Middle East and China.

While the country leads its Central Asian counterparts in planning new renewables, Uzbekistan still faces a number of hurdles in its energy transition away from fossil fuels in pursuit of energy security.

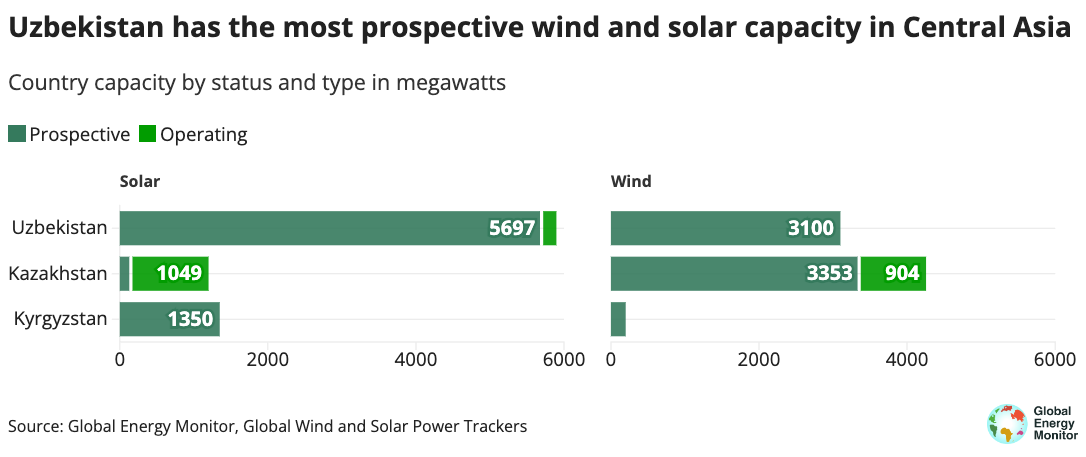

Uzbekistan has a target of achieving more than 30 percent renewable energy electricity capacity (around 15 gigawatts) by 2030. Currently the country has only two large-scale operating solar farms, each 100 megawatts. The country is pursuing a total of 8.8 GW of prospective wind and large utility-scale solar power via projects that have either been announced or are in the pre-construction or construction phases.

Uzbekistan’s prospective portfolio includes 5.6 GW of utility-scale solar and 3.1 GW of wind power at various stages of development. Three-quarters of prospective wind projects and nearly half (48 percent) of prospective utility-scale solar projects are yet to reach pre-construction or construction stages, however, suggesting completion of these projects could be a long way off.

Nevertheless, the bulk of the country’s prospective capacity, 58 percent (5.1 GW), is scheduled to be connected to the grid by 2025. This figure does not count 1.4 GW of capacity that has been shelved or other nascent projects that have yet to reach an advanced stage of development.

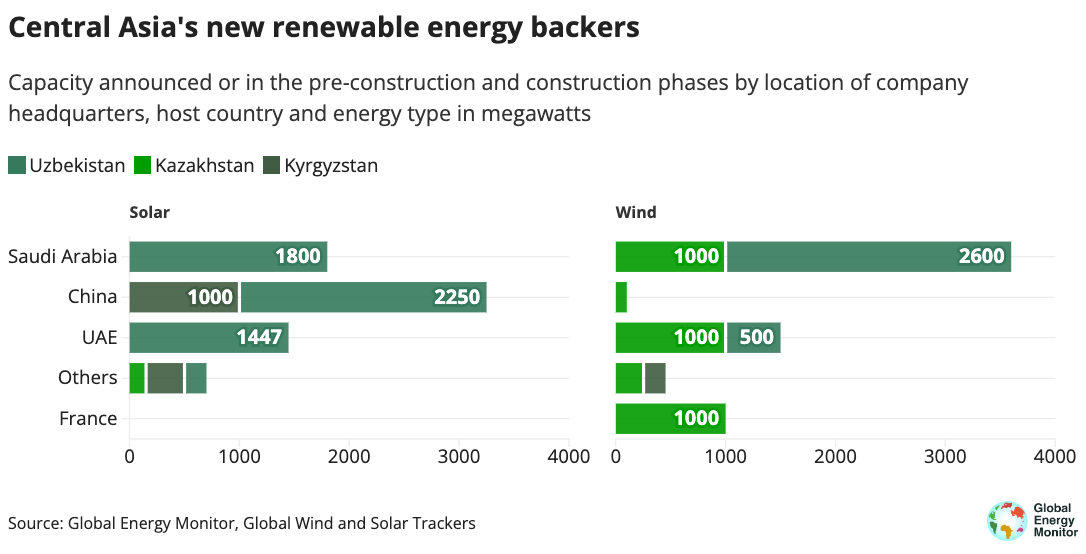

Two key actors in Uzbekistan’s renewable energy development have emerged from the Middle East, with Saudi Arabia’s ACWA Power and the Emirates’ Masdar planning 3.1 GW and 3.2 GW of prospective wind and utility-scale solar, respectively. These two companies account for nearly three-quarters (73 percent) of all prospective capacity in Uzbekistan.

More widely, the two companies are also active in Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan, with Masdar also developing renewables in Tajikistan, solidifying their position as the predominant players in the Central Asian energy sector, and potentially reducing Russian influence in the process. China’s Gezhouba Group and PowerChina are leading prospective solar projects.

While progress on renewables is commendable, Uzbekistan is still heavily investing in the development of oil and gas and remains dependent on fossil gas to generate 85 percent of its electricity. In addition to barriers to renewable energy development, concerns remain about the potential risks of renewable energy projects for local communities and wildlife, including vulnerable and endangered species. Uzbekistan also lacks a plan to phase out fossil fuels, weakening the country’s road to carbon neutrality by 2050.

At the same time, ACWA Power is also planning to use at least 2.6 GW of its wind and solar farms solely for green hydrogen production, still a largely unproven technology. The hydrogen would ostensibly be used locally to decarbonize Uzbekistan’s chemical industry, which is more sustainable than building a 40 GW wind and solar complex for hydrogen export as Kazakhstan currently plans to do. The risks associated with green hydrogen production may undermine both energy security and a just and equitable decarbonization.

Facing the formidable task to achieve energy security and decarbonization, Uzbekistan needs to balance the need for a secure energy supply with other priorities such as reliability, affordability, and equity.