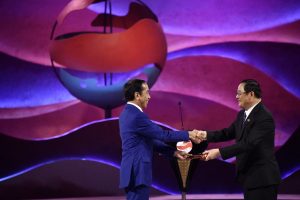

There was a palpable sense of apprehension among onlookers as Indonesia passed the gavel of the ASEAN chairmanship to Laos at its summit in September. Diplomats and observers alike worry that Laos, a diminutive communist state currently facing debilitating macroeconomic instability, may not be able to smoothly navigate the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) through the various challenges facing the bloc, from the conflict in Myanmar to growing tensions in the South China Sea and the intensifying U.S.-China rivalry. Given the stakes involved, it is little surprise that the transition from the most populous and capable member state of ASEAN to its poorest has stirred up some anxiety.

Yet striking a balance between bigger forces has always been the modus operandi for Laos, and ASEAN is among the most prominent theaters in which to observe this balancing act. As the most impoverished and geographically isolated member, sandwiched between historical rivals in Southeast Asia, ASEAN provides an invaluable platform for Laos to liaise with neighbors and external partners it otherwise would have a harder time engaging alone, broaden its economic options and investment opportunities, and promote its image and interests. Laos thus has very good reasons to walk the tightrope carefully and aim to act as a responsible chairman in 2024. In a way, Laos’ operational limitations when it comes to hosting ASEAN events – the lack of infrastructure and diplomatic staffing – comes with a silver lining. As Laos welcomes technical and diplomatic assistance on ASEAN organization from external partners like the United States, Australia, Japan, and Vietnam, these can in turn act as additional channels for partners to voice concerns with Lao diplomats.

Laos has often found ASEAN a useful platform for amplifying its interests. The recently unveiled theme for the coming chairmanship – “Enhancing Connectivity and Resilience” – encapsulates its double vision of becoming “the battery of Southeast Asia” through hydropower development and transforming itself from “land-locked to land-linked,” as well as its preoccupation with its ongoing macroeconomic troubles. In choosing this theme, Laos seemingly recognizes the challenges of “economic and financial difficulties, climate change, natural disasters, and traditional and cyber security issues,” and “the importance of enhancing connectivity and resilience as a means of strengthening the ASEAN community.” These domestic priorities have often been reflected in Laos’ previous tenures as ASEAN chair. Integration and infrastructure are also the most prominent elements in documents such as the 2004 Vientiane Action Program and the 2016 Vientiane Declarations.

Laos’ theme is more inward-looking compared to Indonesia’s more globally ambitious vision, “Epicentrum of Growth,” but they both are fundamentally concerned with economic cooperation, a “core” ASEAN agenda item. It is thus in Laos’ interest to continue with the ASEAN-Indo-Pacific Forum, Indonesia’s realization of ASEAN’s Indo-Pacific Outlook, which was first held this year as a forum for boosting cooperation and investment between ASEAN member-states and their Indo-Pacific partners. The forum, touted by the Indonesians and hoped by them to continue with Laos, could help to broadcast Laos own priorities and perspectives to a broader regional audience. The problem is then whether Laos can articulate (or is even invested in) a perspective on something as broad and global as the Indo-Pacific. Laos’ conservative foreign policy posture does not lend itself well such a concept, and it presently does not appear to have its own Indo-Pacific strategy. It remains to be seen whether being scrutinized by onlookers as the ASEAN chair will compel Laos to break this habit.

With regards to the more controversial issues on the ASEAN agenda, there are reasons to believe that Laos will maintain an even keel, though one should not expect any breakthroughs. On the South China Sea, Laos has shown itself to be capable of balancing the interests of larger powers despite its geographic, economic, and political proximity to China. Unlike Cambodia’s unabashed pivot to China’s positions in 2012 and 2016, Laos, as the ASEAN chair in 2016, managed to strike a compromise between opposing voices on the South China Sea and overcome deadlocks to issue joint statements at that year’s East Asia and ASEAN summits.

In the (rather dramatic) recollections of former Lao Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs Alounkeo Kittikhoun in his recent book on Lao diplomacy, the former chief negotiator during the 2016 Summits assiduously chased all of the interested parties (the U.S., China, Vietnam, the Philippines) and came up with compromises that did not overtly contravene their positions. Kittikhoun concluded the chief lesson from Cambodia’s failure and Laos’ resolution on the South China Sea issue was to “make everybody equally unhappy.” The lesson from this episode seems to resonate even today and will likely be the way Laos navigates its coming ASEAN chairmanship. Echoing Kittikhoun’s sentiments, former U.S. ambassador to Laos, Peter Haymond, in a recent podcast with CSIS gave this formula a facetious twist: the Lao strategy for ASEAN 2024, he said, will be to “piss off everybody equally.”

Bounded by its treaty alliance with Vietnam, Laos supports Vietnam’s international stance on many issues but does not follow Vietnam completely on matters important to its interests. Conversely, Vietnam cannot be too forceful with Laos because it cannot afford to lose its only ally, especially one that flanks most of its vulnerable western border and neighboring China. Thus, on global matters like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine related (but not critical) to Lao interests, Laos has taken the same position as Vietnam’s, but on the South China Sea it has avoided opining and attempts to strike a balance between Vietnam and China. Taking a side would incur unnecessary risks for the still institutionally and economically weak Laos.

This means that the South China Sea issues will not be resolved with Laos at the helm, but it is difficult to imagine that a diminutive, landlocked, communist state with no claims on the South China Sea would be able to solve the problem that has plagued its bigger neighbors for several decades. At best, Laos can only try to provide neutral ground and maintain a balance to the best of its ability. This is reasonable to expect given that Laos’ foreign ministry is currently headed by a veteran minister with a well-established record in the West, while a former ambassador to Vietnam holds the important post of the head of external relations committee of the ruling Lao People’s Revolutionary Party.

Perhaps the more open and pressing question is how Laos will deal with Myanmar, which has no comparable precedent in Laos’ previous tenures as ASEAN chair. It is likely that the crisis, which has strained even Indonesia as the most capable and invested member state, will persist throughout Laos’ chairmanship in 2024. The troika mechanism put into place by Indonesia may nonetheless take some of the burden off Vientiane and at minimum retain the (already modest) progress achieved by Indonesia. The coming troika as an informal, consensus-based mechanism will consist of Indonesia (the previous chair), Laos (the current chair), and Malaysia (the next chair). This means that voices more critical of the junta will have greater weight than they might otherwise have had, given Laos’ reluctance so far to criticize the actions of Myanmar’s military government.

Increased scrutiny over what goes on in Vientiane could also anchor the official line on Myanmar and prevent it from slipping into accommodation. If Laos is indeed more susceptible to foreign inputs on issues beyond its expertise and interested in balancing interests, it may find it more agreeable to uphold the policy line of ASEAN as the “path of least resistance.” Paying lip service to the bloc’s Five-Point Consensus peace plan and leaving the issue to vested interests in ASEAN will not harm Lao interests, even if it may disappoint many outside observers.

One factor differentiates Laos from the past and future ASEAN chairs: it is the only chairman since the crisis began with the military coup in 2021 that borders Myanmar and will remain so for the coming years; the past three chairs, Brunei, Cambodia, and Indonesia, do not border Myanmar, while Myanmar has ceded its chairmanship in 2026 to the Philippines. The proximity to Myanmar and its inadvertent patron, Thailand, may compel Laos to avoid upsetting the country’s military junta.

However, Myanmar’s importance to Laos is not a given. Myanmar-Laos trade primarily consists of basic commodities; totals in the single-digit millions of dollars and forms a minor part of their overall trade, unlike Thailand’s billion-dollar trade with Myanmar and interests in resources like natural gas. The Lao border with Myanmar is also the shortest that it shares with any country, extending for just 238 kilometers in a remote part of both nations, compared to the much more extensive Thai border with Myanmar, which runs for more than 2,400 kilometers. Lacking comparable historical complexity and incentives in Thai dealings with Myanmar, if Laos “has been rather supportive” of Thailand’s renegade engagements on Myanmar, as Hutt observed, this is likely to have been borne of convenience rather than serious interest in defending the military junta in Myanmar.

The festering Myanmar crisis has in fact negatively affected Laos more than it has for Thailand through the influx of drugs and transnational crimes across the region’s porous frontiers. Meth from Myanmar has flooded the black market in Laos and become even “cheaper than beer and fried rice,” precipitating an unprecedented drug epidemic and alarming rise in crime (two-thirds of which is now drug-related) in a country already wracked with economic pain. Laos declared drug prevention and control a “national agenda” in 2021 and has extended the anti-drug program for a further two years in 2023, deeming the drug fight as “a hard and long-term battle and the most urgent task currently.”

Ambassador Haymond has also confirmed that counternarcotics will be a national priority in the coming year for Laos, and that other ASEAN states, which have also been affected by the flow of drugs from Myanmar, have voiced concerns about this. It is likely that counternarcotics and policing will be raised by Laos during its chairmanship of ASEAN. The under-equipped, under-staffed, and under-trained Lao police force is overwhelmed by these problems, and thus will be interested in help from other ASEAN and other nations further afield.

There is currently an opportune confluence of interests on this matter. China recently has upped the ante on counternarcotics and efforts to shut down online scam activities along its border with Myanmar. Vietnam likewise has cooperated well with Laos on border defense, counternarcotics, and transnational crime. Thus, counternarcotics is a topic ripe for cooperation and progress in the coming ASEAN year, if not on its own, then in relation to Myanmar, where the junta has benefited from criminal enterprises that have produced vast amounts of narcotics. It is entirely within Laos’ national interest – and capacity – to give counternarcotics a prominent place on next year’s ASEAN agenda to both bolster both its own fight against crime and tighten the valve on the junta’s illegal income. Counternarcotics already figures in the ASEAN frameworks and could be further prioritized during the Lao chairmanship, given adequate attention and support.

Nonetheless, this modestly optimistic outlook comes with crucial caveats. First, China’s influence over Laos is several orders of magnitude greater than what it was in 2016. Laos is firmly and grossly indebted to Chinese state banks over several mega infrastructure projects in the country, most notably the Kunming-Vientiane railway, and has even ceded a stake of its national power grid to China. Laos may want to steady its relations with China, Vietnam, and the U.S., but this stranglehold of the Chinese economy presents a monumental constraint on its capacity to balance relations. This will not be helped by the U.S.’ and Indonesia’s likely preoccupations with their presidential elections next year. In conjunction with unmatched Chinese influence, it is entirely possible that their distractions could take some pressure off Laos on urgent issues, to the detriment of resistance interests in Myanmar and diplomatic progress on the South China Sea disputes.

A final point of concern is Laos’ unfamiliarity with criticism and civil society, a major factor in the Myanmar crisis. The Lao regime has historically been greatly intolerant to internal criticism and protests and the recent public murder of a regime critic demonstrates that Laos has not changed so much in this regard. It is hard to tell how Laos will react to the coming international scrutiny, from states as well as non-state actors, on the Myanmar issue. One can certainly expect some degree of awkwardness when Laos is, for instance, urged to open dialogue with ethnic resistance fighters in Myanmar, similar kinds of entities to the Hmong insurgents and rebels that Laos fought for decades to suppress within its own borders. There is no telling how the Myanmar crisis will play out in ASEAN next year under the aegis of a government whose relations with Myanmar remain shrouded in obscurity.