On the night of December 28, 2023, just a few days before New Year’s, my husband and I went through an unsettling experience in Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city. We were on our way to Hasan Square to grab some books when, out of nowhere, two guys on Rashid Minhas Road started yelling at us. We thought they were just randomly shouting, so we brushed it off and kept going on our motorbike.

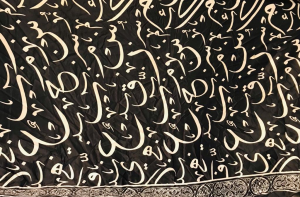

But things got even weirder. The men became aggressive and started following us to Nipa Chowrangi. I got pretty scared and told my husband just to keep driving. They kept yelling, and it got even scarier when they accused us of not being Muslim because of some Urdu writing on my shawl. We tried explaining, but they weren’t having any of it.

One of the guys said, “Musalman nahi ho kya?” (Are you not Muslim?) multiple times. We were extremely confused. Then, he pointed at my shawl and claimed that the names of Allah and the Prophet were written on the cloth. “Ap be-hurmati karahe ho” (You are showing disrespect), he berated us. It was surreal.

We tried to reason with the men, pointing out that the shawl only depicted letters in the Urdu language, but they forced me to take off my shawl right there on the road. It felt so humiliating. One man threatened us further, saying that if we had not stopped the bike he would have run us over.

He ended with the chilling declaration, “Agar itna shoq hai tou dupatta pehno na” (If you’re so fond of it, then wear the dupatta). He was making me aware of the fact that they didn’t consider what I was wearing a dupatta – and as a result, they felt they could do anything with me. And what this “anything” implies in Pakistan made me dread the possibilities of what further could have happened to me.

Eventually the men and the whole crowd just scattered, leaving us stuck there.

We finally made it to Hasan Square, but we couldn’t shake off the worry that they might come back. Little did we know that a simple book-buying expedition would take an unexpected turn, with my love for literature colliding with someone else’s religious fanaticism.

Aftermath of the Incident

Feeling a responsibility to the community, we shared our experience on Facebook. We wanted to let others know about what happened, thinking it might help them be prepared in case they faced a similar situation.

The post generated massive traction, with people all over the country talking about the issue.

The vast majority of people supported me, expressing their dismay and concern over the safety and security of people in the country.

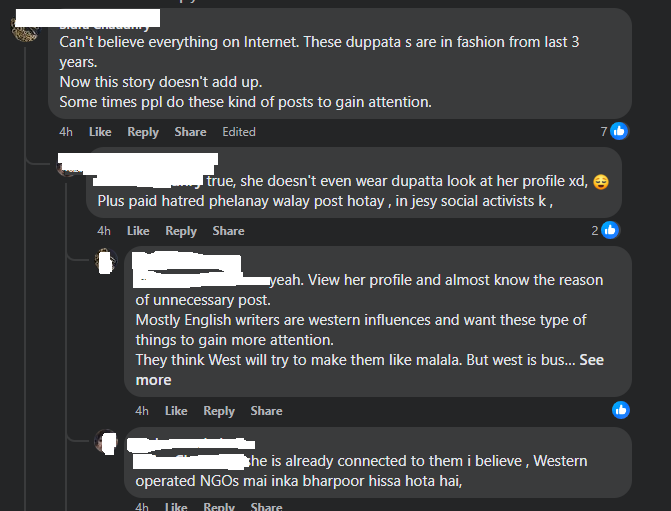

However, a few put the blame on me for wearing this shawl in the first place, or accused me of making up the incident. I was called a liar, a “fame monger” and a “foreign agent.”

Some even went to the extent of analyzing my entire profile, commenting on my choice of clothing, and criticizing me for not wearing a dupatta in most of my pictures.

Backlash from people after I shared my story. Photo by Waqas Rabbani, the author’s husband.

Blasphemy Laws and Pakistan

In Pakistan, blasphemy accusations are a matter of life and death. Accusing anyone of blasphemy triggers laws set in place to criminalize offenses against religious sentiments, particularly those deemed offensive to Islam. These laws were introduced in the 1980s during the Zia regime and have since become a source of controversy and concern both within the country and internationally.

The primary statutes related to blasphemy include sections 295-B and 295-C of the Pakistan Penal Code. Section 295-B pertains to the desecration of holy scriptures, prescribing three to five years of imprisonment for anyone found guilty of willfully defiling the holy book. Section 295-C deals with derogatory remarks against the Prophet Muhammad and carries the death penalty or life imprisonment for blasphemy against the Prophet.

The blasphemy laws in Pakistan are marred by various issues. One of the primary problems lies in the frequent misuse of these laws, often as a tool for personal vendettas or to settle scores. The consequences of blasphemy accusations often result in violent vigilantism, with mobs taking matters into their own hands, resulting in lynching, attacks, and even deaths.

Cases like those of Mashal Khan and Priyantha Kumara serve as distressing examples of this horrifying trend. Accusations of blasphemy, later proven to be baseless, tragically led to their demise before the verdict could exonerate them.

Religious minorities bear the brunt of discrimination and persecution due to Pakistan’s blasphemy laws, whether it’s the case of a Christian teenager, Rimsha Masih, who was put into jail for having a discussion with a coworker about religion or a Pakistani Christian minister, Shahbaz Bhatti, who was killed for asking for a change in the country’s blasphemy laws.

While there are multiple examples of this persecution, the most prime example is the incident that happened six months ago in Jaranwala, where mobs attacked 26 churches and 80 homes of Christians on accusation of blasphemy. Police brushed it off, calling it a suspected foreign plot, aiming to divert attention from the alleged mistreatment of Christians in India to incidents in Pakistan.

I am forcefully reminded of the old Latin phrase “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes,” meaning, who will guard the guards? If the protectors of the country will sweep everything under the rug, who can we expect protection from?

False accusations have become alarmingly common, leading to severe consequences for innocent individuals. The laws are criticized for their vague language and lack of clear definitions, contributing to the difficulty in determining what qualifies as blasphemy.

Additionally, the burden of proof is often unfairly placed on the accused, creating a challenging situation for individuals to defend themselves.

I myself was just a dupatta away from becoming a casualty to blasphemy laws in Pakistan. When I shared my experience, several individuals reached out, sharing their own stories of similar ordeals in the country.

Ahmed Khan* recounted a recent incident involving a family member in Lahore: “My relative had worn an ajrak printed with the Sindhi alphabet Alif Bay, and a group of women in Shalamar Garden followed her, pressuring her to remove her dupatta ajrak. They wrongly assumed it contained prints of Quranic verses.”

Salma Kamal* shared a similar story: “While I was on public transport, clad in a kurta adorned with Sindhi alphabets, a group of three to four women approached me. They continuously criticized my attire, mistakenly assuming that I was wearing Quranic verses. I had to repeatedly clarify that it was not the Quran but Sindhi alphabets.”

Factors Contributing to Mob Violence and Blasphemy Accusations in Pakistan

The issue of mob lynching and false accusations of blasphemy in Pakistan is complex and can be attributed to a combination of factors. While lack of education is one of the factors, it is essential to recognize that the issue is multifaceted and involves social, political, and economic dynamics.

The influence of extremist ideologies and groups creates an environment where individuals feel compelled to take the law into their own hands in the name of protecting religious sentiments.

In 2011, Mumtaz Qadri, a Pakistani police officer, assassinated Governor Salman Taseer for opposing blasphemy laws and supporting a Christian woman, Asia Bibi, who was sentenced to death over blasphemy accusations (she was eventually acquitted, but not before spending 10 years of her life in detention). Qadri believed he was defending Islam and became a symbol for extremists, gaining public support despite condemnation from others.

Another factor is impunity. Weak implementation of the rule of law and impunity for those involved in mob violence can encourage further incidents. Perpetrators often escape punishment, which reinforces a culture of vigilante justice. In 2014, a Christian couple, Shama and Shahzad, were accused of blasphemy and subsequently lynched by a mob in Kot Radha Kishan. The weak implementation of the rule of law was evident in this case, as the police were criticized for failing to protect the victims and for not taking swift action against the attackers.

Economic challenges and disparities also play a major role in increasing social unrest, making it easier for extremist ideologies to gain traction. Individuals find it easier to use religion as a means of expressing frustration and anger.

Additionally, political manipulation contributes to the misuse of blasphemy laws in Pakistan. Politicians exploit religious sentiments for their own gain, contributing to the polarization of society and the marginalization of certain groups. In 2018, Tehreek-e-Labbaik Pakistan, a political party, protested the acquittal of Asia Bibi. Politicians, fearing unrest and wanting support from religious groups, negotiated with the TLP. The agreement, seen as giving in to protesters’ demands, reinforced the idea that politicians exploit religious sentiments for political gain.

For me, the entire issue of blasphemy and the violence that it can inspire was a distant issue – one that had no bearing on my day-to-day life as an individual living in a metropolitan melting pot like Karachi.

This incident with a printed shawl and the blatant and open aggression it inspired, and the subsequent stories I became aware of, have changed my perspective entirely.

If blasphemy is so vague and subjective that something as simple as a printed shawl can inspire such open aggression and threats of violence, is anyone truly safe from being accused unjustly?

After I shared this issue on social media, many young women responded by saying they have a similar dupatta and have decided to not wear it again. It broke my heart!

In a country where women already suffer all kinds of violence and all manner of condemnation and judgments on their choice of dress, this incident shows us that there’s more out there for us to be afraid of. The situation is apparently not getting better; in fact, quite the opposite.

*Names have been altered to protect the identity of the sources.