Papua New Guinea (PNG) is digging out from riots that erupted on January 10 and rapidly turned Port Moresby into a “war zone.” Crowds took advantage of police striking over tax increases, and looted and burned shops and businesses in a spree of damage estimated at 1 billion kina ($300 million). 22 people were killed in the capital as well as the city of Lae.

Over a week later, Port Moresby has reverted back to its usual bustle, though the police presence remains high. The reckoning continues, with investigations underway into the conduct of senior police officers and relief efforts being devised to aid business owners, employees, and producers whose property and livelihoods were torched in the melee.

Many speculated that Prime Minister James Marape’s leadership would topple as the riots exposed deeply entrenched inequities and dysfunctions his government has not adequately addressed. The gap between the promise and delivery of economic betterment and opportunity is a political problem Marape, like almost every current government, faces and must work to address. The riots certainly revealed a potent mix of economic desperation and opportunism.

Marape’s political success, despite these challenges, has been due to his championing of a unifying cause that has has deep reverberations in PNG and in recent months, on the world stage. Marape has been rallying his nation around Christianity, namely a brand of evangelicalism that is on the verge of a whole new level of influence. The political pressure stemming from the riots will likely mean even more emphasis on the Christian faith, particularly as PNG is likely to declare itself a “Christian nation” in early 2024.

What will this enshrining of Christianity as the state religion mean for PNG and the Pacific? What does it mean for the duel in the Pacific for influence between China and the United States, and how has it factored into PNG’s support for Israel when other allies began falling away? The implications of PNG’s move to become a Christian nation is one of unlikely connections between causes, cultural movements, and intersecting geopolitical contests that cut across many grains.

Papua New Guinea is the second-largest Pacific country after Australia. PNG’s population is estimated to be between 10-17 million, with estimates changing by many millions over the past year. The large uncertainty surrounding PNG’s population count highlight some endemic features of the nation, which, despite nearly 50 years of nation-building since independence from Australia in 1975, remains highly fragmented. Over 800 languages are spoken by PNG’s population scattered across over 400,000 square kilometers encompassing 600 islands, many with rugged, tropical, and volcanic terrain. This demographic and geographic complexity mean that PNG’s state institutions are weak and government reach is very uneven. The lack of accounting for births is a key indicator of this.

PNG defies categorization. On the one hand, it identifies as a Pacific nation. Yet its geographic size, location on the border of Southeast Asia and the Pacific, its resource-richness, its large and significantly youthful population, and a growing middle class set PNG on a trajectory akin to a Southeast Asian tiger economy. PNG is also reminiscent of many post-independence African nations. Tribal factions carve up the political landscape and its resource wealth allocations preoccupy government business. Weak state institutions, rampant corruption, and low quality of life persist despite the post-independent socialist policies of big budgets in health and education, which have produced a bulging public service with limited impact. Its literacy rate of less than 64 percent is the lowest in the Pacific.

Despite having one of only three militaries in the Pacific region, PNG has remained resistant to coups (unlike Fiji, which has had four since 1987) and complete lawlessness, although PNG is regularly startled by outbreaks of violence. The 2022 election sparked a spate of violence that killed at least 50 people and displaced 90,000, with women and children the most impacted. The riots at the beginning of 2024 are another, more contained, case in point.

The biggest threat to PNG’s national cohesion is the autonomous state of Bougainville. Its president, Ishmael Toroama, has set a 2027 deadline for Bougainville independence after the national government stalled acting on the overwhelming vote (nearly 98 percent) in favor of Bougainvillean independence in late 2019. The fraught history of Bougainville and Port Moresby since independence, which includes a vicious war from 1988 to 2001, has always centered on the Panguna copper mine, one of the largest and richest on the planet. The mine will remain the epicenter of negotiations as the status of Bougainville is resolved.

How does PNG’s move to become a Christian nation map onto this complicated context?

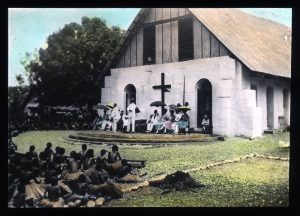

PNG’s interlocking belief systems of custom (traditional creeds) and Christianity have coexisted to varying degrees since 1847 when the first missionaries, Roman Catholics, arrived. Today, the Catholic Church is the largest in PNG, with 30 percent of the population embracing the Catholic faith. Many Christian missionaries of differing denominations and national origin, predominantly from Europe or Britain via Australia, followed, establishing regional spheres of influence.

From the 1970s, Pentecostal ministries inspired by the revival movements epitomized by U.S. televangelists began to permeate PNG and other parts of the Pacific. Using mass communication and modern gospel music, these new faiths linked biblical messages to concepts like the “prosperity gospel.” The influence of these churches was powered by generous donors locally and abroad. While their influence rose in PNG power structures, they did not necessarily compete or aim to displace older, traditional churches.

Furthermore, they saw the state of Israel as the fulfillment of end-time prophesy and, more importantly, presaging the return of the Messiah. In accordance with that perspective, Marape has been demonstrably supportive of Israel.

Ahead of the Gaza war, Marape traveled to Israel to personally open the country’s embassy in Jerusalem, with PNG just the fifth nation to make this controversial move. Since the October 2023 outbreak of hostilities in Gaza, Papua New Guinea and other Pacific nations have played a surprisingly pivotal role in demonstrating support for Israel. At the end of October, Papua New Guinea was one of the six Pacific states (and 14 states in total) that voted in the United Nations to oppose a humanitarian truce. On December 12, several other Pacific Islands Forum members broke with the U.S. and Israel to support a resolution calling for an immediate humanitarian ceasefire. Papua New Guinea, along with the Federated States of Micronesia and Nauru, remained consistent in their support for Israel even as civilian casualties and criticism have mounted.

Marape’s strong support of Israel meshes with his overall approach to faith and politics. When Marape became prime minister in 2019, he formulated a political ideology that aimed to position PNG as the “Richest Black Christian Nation” over the next 10 years. He also began inquiries in 2020 into a constitutional change that would enshrine Christianity in the nation’s constitution. For Marape, “the Christian nation” is a unifying language and value system that almost all Papua New Guineans can subscribe to. In April 2021, Marape said that “there is a need to redefine and give absolute prominence to our Christian beliefs… In our nation of a thousand tribes, I believe Christianity can bind us together as one nation.”

Christianity is already pervasive in PNG daily life. Prayers are offered throughout the week, devotions are conducted in workplaces and usually before major decisions are made, and church leaders are regularly consulted. As is common elsewhere in the Pacific, communities tithe heavily to their churches. While most children attend government schools, churches play a key role in administering and supporting PNG’s education systems.

The possible constitutional recognition of Christianity is not expected to bring about drastic change to daily life, though questions about weekend trading and clashes with holy days have not yet been answered. Nor has the question about whether other minority faiths will require permits for their festivals. It also remains to be seen if Marape’s church, the Seventh Day Adventists, will become over-represented in his government.

PNG’s legal codes already criminalize homosexuality and abortion. PNG’s conservativism on gay rights led to open criticism of the U.S. embassy for flying the rainbow flag during Pride Month in June 2023.

In this way, and numerous others, PNG is more culturally aligned with MAGA America, rather than the progressive agendas of the Biden administration or the left-leaning aid and development agencies that spearhead U.S. outreach. As an example of how influential these connections are, in 2022, the entire upper echelon of the public service, business, cabinet, and judiciary met in a series of seminars by the U.S. Christian motivational speaker, John Maxwell, and his 200 partners for 10 days.

Faith connections, particularly with the U.S., are a missed opportunity for governments looking to connect with PNG. There is already a great deal of activity such as second-generation U.S. missionary families operating schools, health facilities, safe zones for those suffering from sorcery accusations and gender-based violence, and motivational programs for millions of Papuan New Guineans. Yet the West, through its various foreign affairs and international relations institutions, has not fully utilized faith-based diplomacy in geopolitics. Instead, they have opted to use it as a subset of civil society engagement in social and related regional issues such as climate change.

Ambitious aid programs have seen Australian-based churches affiliated with PNG churches project manage various education, health and justice programs. But when connecting to their charity arms, Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) distances itself from biblical teachings and encourages partnerships and service delivery.

As far as the geopolitical duel with China is concerned, China has no answer to the Christian culture and the influence it has on Pacific and PNG communities and leadership. China has invested heavily in PNG over many years. In 2023, Marape discussed a free trade agreement with China, which already buys half its products. Yet Marape is adamant that security is not a topic he has discussed with China, whereas he signed a Defense Cooperation Agreement with the United States in June and a Bilateral Security Agreement with Australia in December 2023. The security piece is an enormous part of the geopolitical duel with China, and it would seem that the U.S. has the upper hand.

The U.S. is indisputably winning in faith-based connections and shared values, although it’s the right wing of U.S. politics leading that charge. Christian faith is a bridge for the U.S. to connect to PNG that arguably can be further nurtured and strengthened.