In the rugged terrain of Afghanistan, amid a backdrop of perpetual struggle and resilience, a young girl named Omia Karimi emerges as a guiding light of hope and determination. At just 12 years of age, her youth belies a spirit undaunted by the challenges that define her city, Kabul.

In Afghanistan where the aspirations of women and girls are often stifled by societal norms and political turmoil, Karimi dares to envision a future unbound by the constraints of history, poverty, and war – a future in Afghan politics. Her ambition gleams as a testament to audacity and resilience.

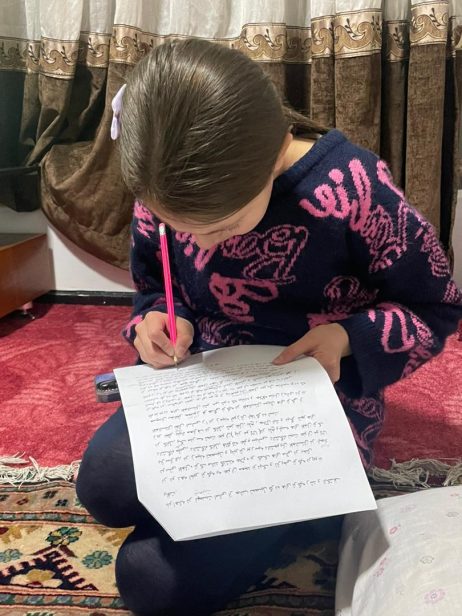

Karimi shares her reflections on Afghanistan, colored by the innocence of her own imagination and the lessons learned at a private school in Kabul. While her understanding of the country’s history and its people may be limited, and the future may be profoundly uncertain, she remains confident – particularly in her writing skills. She recently earned the second literary prize at her school for an article she wrote. Her father proudly shared the news on X, formerly Twitter, while also calling for an end to the ban on girls’ education above grade six.

Such calls have become a routine for numerous Afghan parents. On Sunday, Hamid Karzai, the former president of Afghanistan and father of three girls, expressed his disappointment regarding the closure of schools. Like thousands of other Afghan girls, his daughters will soon be deprived of their right to attend school if the ban is not lifted.

Calling upon authorities to lift the ban for all girls, the former president rued the closure. He noted the arrival of Nowruz, the ancient festival of spring celebrated across South and Central Asia, traditionally marks the celebration of the new school year for Afghan children.

Usually, the start of the new school year “would be like Eid for our children, girls and boys,” Karzai wrote. “Unfortunately, the girls of the country have been deprived of education for almost three years.”

This year, Nowruz fell on March 20. Nowruz, meaning “new day,” is an ancient festival that predates Islam. Across South and Central Asia, people celebrate Nowruz as a time of renewal and rebirth, symbolizing the arrival of spring and the rejuvenation of nature. It is a time to express wishes for prosperity, health, and a bountiful harvest in the coming year.

After Nowruz, school bells ring in government schools across the country, signaling the start of the academic year. Despite numerous obstacles, millions of girls and boys consistently enroll in school each year, demonstrating a collective determination to pursue education despite the odds.

Yet, amid this festival of renewal, the onset of the new school year casts a poignant shadow for countless girls across Afghanistan, who are forced to bid sorrowful farewell to classmates and the cherished school milieu. For the third consecutive year, Afghan girls above grade six will not be allowed to enter classrooms on the first day of the education year; it constitutes a serious violation of a basic human right.

After regaining control of Afghanistan, despite previous pledges to safeguard women’s rights, including the right to education and employment, the Taliban swiftly enforced more stringent regulations. Consequently, millions of Afghan girls remain deprived of access to schooling.

According to a 2023 United Nations report, over 130 million girls worldwide are deprived of access to education. Significantly, Afghanistan stands out as the only country where education beyond the primary level is prohibited for women and girls.

The Taliban rationale behind the closure of schools for girls remains unclear, particularly considering that Islam does not prohibit education for girls. The Taliban cited “religious and cultural” reasons, asserting their efforts to establish a conducive educational environment for older female students. But not real effort has been made to establish schools for girls above grave six.

The U.N. report denounced the discriminatory policies of the de facto authorities in Afghanistan, which prevent women and girls from accessing secondary schools, universities, and other educational institutions. These policies “amount to abuse that not only harm women and girls, but are also seriously damaging the country and its future,” the report said.

For Karimi, who is starting grade four this year, Nowruz still heralds a glimmer of hope. Her story also reflects the resilience of Afghan women in the face of adversity, as they strive for education and empowerment in a country where millions of girls are denied schooling, trapped in a cycle of poverty and discrimination perpetuated by the country’s near-global isolation and the Taliban’s stringent regulations.

For Afghan women, life has never been easy Karimi’s mother, in her early 30s, is one of the millions of women in Afghanistan who were unable to attend school due to the ongoing strife in the country.

Education in Afghanistan has long been a primary target of violence, dating back to the Soviet invasion of the 1970s. Schools were continuously set ablaze, and both students and teachers fell victim to the conflict. This unfortunate trend persisted over the past two decades, exacerbated by widespread corruption and embezzlement of funds by successive Afghan governments.

Despite receiving billions in foreign aid intended to support education for all Afghans, significant challenges remained even under the former Republic. Millions of children were unable to access schooling, and Afghanistan’s education system continued to grapple with issues such as ghost schools and teachers, further compounded by escalating conflict. The deterioration of security and rampant corruption impeded progress that could have otherwise transformed the country’s educational landscape.

A 2018 Human Rights Watch report said that the number of children attending school fell, with 60 percent of Afghan girls not enrolled in school during that year. In the same year, UNICEF reported that approximately half of Afghanistan’s children aged between seven and 17 years old – totaling 3.7 million – were unable to access education. This alarming statistic was attributed to the ongoing conflict and deteriorating security conditions in the country, compounded by pervasive poverty and gender discrimination against girls.

Having missed out on schooling, Karimi’s mother entered into an early marriage, a significant social issue often associated with domestic violence and abuse, as well as Afghanistan’s high rates of maternity. However, she took steps to learn reading and writing. With the support of her husband, she arranged for a tutor. Now, she is helping Karimi fulfill a dream that she herself could not achieve: completing a formal education.

Omia Karimi, writing schoolwork in her Kabul home. Photo courtesy of her father, Sayed Ahmed Karimi.

If the Taliban’s ban persists, Karimi’s educational journey may face an abrupt halt after sixth grade. That means a significant reservoir of the country’s human potential – optimistic and enthusiastic young thinkers like Karimi – remains untapped and wasted.

In Kabul, she might find refuge in one of the clandestine learning centers where women extend education to girls beyond grade six, reportedly with support from organizations outside the country, primarily in the United States. However, this alternative does not equate to receiving a formal education.

Despite the secrecy surrounding these educational efforts, it’s becoming increasingly apparent that the existence of so-called secret schools in Afghanistan may not be as covert as initially presumed. If so many girls are attending these schools, it’s plausible that the Taliban, with their sophisticated intelligence network, are also aware of their existence. Moreover, women’s participation in various sectors of society, including employment at airport checkpoints, banks, and hospitals, further underscores the visibility of women’s roles in public life. While edicts from on high ban such activities, the local enforcement seems to be spotty – perhaps purposefully so.

Many high- and medium-ranking Taliban officials privately acknowledge the fundamental human right to education for women and girls. Some even continue to speak publicly in support of education for girls. For instance, Abbas Stanikzai, the deputy foreign minister of the Taliban, spoke at a gathering of girls at a religious school in Kabul in February, emphasizing that educating both girls and boys is crucial for the country’s development.

Similarly, numerous medium-ranking officials in Afghanistan recognize the significance of girls’ education for the well-being of their own daughters. Some have publicly voiced support for girls’ education, highlighting the adverse consequences of banning it, which they believe creates a divide between the ruling elite and the general populace.

Despite these sentiments, there seems to be a consensus among many Taliban members that decisions regarding girls’ education ultimately lie in the hands of a “supreme power,” such as the emir or the supreme leader, who has not appeared to the public. The Afghan public has only heard his voice messages as of yet.

This raises questions about the decision-making process within the Taliban hierarchy, suggesting that even within the organization, there may be a broader agreement about the necessity of girls’ education. However, the final decision appears to be made by a centralized authority, leaving even supportive Taliban members powerless to enact change without approval from above.

That does not seem likely to happen in the near future.

What is unmistakably clear is that Afghanistan and the plight of its girls and women demand urgent attention from the international community. Increasing sanctions as a pressure tool on the de facto government in Afghanistan may seem like a viable option to certain observers, but the effectiveness of such tactics remains uncertain. Moreover, the continuation of existing sanctions has undeniably worsened the humanitarian crisis. Implementing additional sanctions would only exacerbate the situation, particularly for women and girls who, due to numerous restrictions, are now heavily reliant on men for support.

In the absence of a substantial adversary to the Taliban, be it political or military in nature, the international community, particularly the United States, is left with no alternative but to pursue a direct, robust, and substantively engaged approach toward Afghanistan.

With nearly half a century of war and conflict ravaging Afghanistan, resulting in millions killed, maimed, and displaced, the war-weary Afghan populace finds itself grappling with entrenched poverty and the enduring ban on education. These two key issues appear intricately interconnected, exacerbating the challenges faced by ordinary citizens striving for a better future.

Despite the harsh realities on the ground, certain lower-ranking members of the Taliban persist in the belief that even if the ban on education were lifted, the United States government would not relax sanctions, allow Taliban representation at the United Nations, or aid in their integration into the global diplomatic community.

In the meantime, the future prosperity of young girls like Omia Karimi hangs precariously in the balance within Afghanistan’s turbulent landscape.