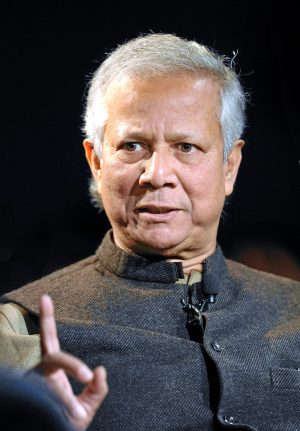

Bangladeshi Nobel Peace Laureate Dr. Muhammad Yunus is facing jail time.

On January 1, a Bangladeshi labor court convicted Yunus for violating the country’s labor laws and sentenced him to six months in prison. Yunus is facing charges of money laundering, tax evasion and corruption in some 198 cases. His jail term is yet to begin as he is out on extended bail.

Yunus is the founder of Grameen Bank, which gives loans to small entrepreneurs who would otherwise not qualify for bank loans. He is known as the “banker of the poor.” His microfinancing efforts have been replicated and celebrated in many countries worldwide. In 2006, Yunus and his Grameen Bank were jointly awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. He is also a recipient of the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. In a nutshell, Yunus is probably the most celebrated living Bangladeshi in the world at present.

Yunus’ supporters and human rights groups believe that the cases against him are politically motivated. They allege that Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina is carrying out a personal vendetta campaign against him. The government denies this allegation and argues that it has no control over the judicial process. However, judicial actions in Bangladesh over the last 15 years have regularly aligned with the ruling Awami League’s interests. Last year, Bangladesh’s Deputy Attorney General Imran Ahmed Bhuiyan publicly said that cases against Yunus are tantamount to judicial harassment. Bhuiyan was dismissed from his position soon after, indicating the tight government control over the judiciary.

Yunus’s international network of friends is standing up to defend him. In an open letter to Hasina in 2023, more than 170 influential world figures, including former U.S. President Barack Obama, former U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and over 100 Nobel laureates called on Hasina to halt the “continuous judicial harassment” of Yunus.

While many in the international community and Bangladesh respect Yunus, Hasina has called Yunus a “bloodsucker of the poor,” a reference to the alleged high interest charged on loans issued as micro-credits.

What underlies Hasina’s relentless campaign against Yunus? The reasons are complex and could be found in the amalgam of Bangladesh’s history, personalized animosity, and the gradual decline of democracy and human rights.

The relationship between Hasina and Yunus was not always bitter. In fact, they were once allies. In 1997, Yunus and his high-profile network organized a Microcredit Summit in Washington D.C. Over 2,000 people from 100 countries attended the summit. Not only was Hasina a co-chair at that summit, but she was the first speaker among 18 other high-profile speakers, including the U.S.’ then First Lady Hillary Clinton and Queen Sophia of Spain. In her speech, Hasina championed micro-credit.

Hasina first came to power in 1996 after 20 years of political struggle. She was likely given a high-profile role on the world stage at a summit in the heart of the U.S. capital only because of Yunus, who was a core organizing member of that meeting. While Hasina was at the start of her long innings in power, Yunus was already an established global phenomenon.

In 2006, the then ruling party, the Khaleda Zia-led Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), and the Hasina-led AL, which was then in opposition, were locked in a political stalemate over the election administration. AL demanded a caretaker government, which the BNP was refusing to concede. Deadly violence ensued on the street. A military-backed civilian caretaker government stepped in and imprisoned both Hasina and Zia.

In 2007, when Hasina was in prison, Yunus floated a political platform, Nagorik Shakti or Citizen Power. In an open letter that was published in newspapers, he wrote: “After getting your immense response, I have decided to join in your effort to create new politics. I will join politics and form a political party.”

Importantly, Yunus mentioned that his politics will be the politics of materializing the ideals of the 1971 Liberation War, which closely resembles the AL’s political agenda — the party projects itself as the custodian of the ideals of the Bangladeshi freedom struggle. However, a few weeks later, Yunus left politics. Hasina and Khaleda were freed from jail, general elections were held in 2008 and Hasina formed the government with a landslide win. Yunus’s announcement of his political ambitions when Hasina was in prison may have triggered Hasina, as she could have perceived Yunus’s move as a betrayal. In Hasina’s eyes, Yunus had thus emerged as a political threat.

Their relationship began to fray rapidly when Hasina’s government removed Yunus from the Grameen Bank over age concerns in 2011. The situation worsened when the World Bank canceled a loan for a major bridge project over the river Padma over corruption concerns, with Hasina accusing Yunus of influencing the decision, which Yunus denied. No evidence was presented by Hasina or her allies to substantiate their allegations.

Hasina has been in power for the past 15 years, and during this period, she has tightened her grip over all of Bangladesh’s institutions be it parliament, the judiciary, the bureaucracy, or the Election Commission. In addition to the politicization of these institutions, she has silenced the opposition, media and critical voices. Bangladeshi law enforcement officials are allegedly responsible for more than 600 disappearances since 2009, nearly 2500 extrajudicial killings between 2009-2022, and torture.

Hasina’s rival Zia was imprisoned on several dubious charges. While her prison sentence has been suspended for now due to her ill health, this is subject to strict conditions. A New York Times report last year noted that millions of opposition activists are facing politically motivated charges.

Yunus did not raise his voice throughout this period. Had he done so, it could have garnered much more international attention towards Bangladesh’s rights situation since he is a high-profile Bangladeshi. However, he prioritized his international speaking engagements over the domestic fight against the AL government’s authoritarian slide.

It is only after the labor court’s verdict against him in January that Yunus has spoken up on human rights and democracy.

His strategy of silence over rights violations has backfired. With AL forming the new government in 2024, the BNP and civil society are being further weakened, and Yunus is now almost alone with only a set of influential international actors, who are balancing between supporting Yunus and enhancing engagement with Hasina, keeping him company.

Hasina did not succumb to American pressure to hold a free and fair election in January this year, a sign of declining American influence in Bangladesh. To the Bangladeshi ruling establishment, Yunus is an American ally.

The Yunus case underscores the changing nature of balance of power and foreign influence in Bangladesh where America and the West are in decline and the country is now deeply embedded in authoritarianism.