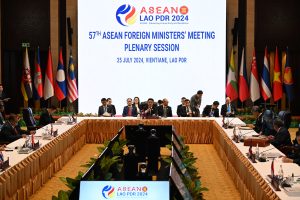

As last week’s Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) meetings came to a close on Saturday, the bloc’s 10 nations issued their customary annual joint communique, laying out their positions on a range of ASEAN initiatives, and a host of regional and global issues.

One section that has attracted close attention over the past few years has been the paragraphs of the communique dealing with the civil war in Myanmar – all the more this year, given the dramatic battlefield developments that have taken place since October, when a coalition of ethnic armed groups launched an offensive in northern Shan State that has cascaded into junta losses across the country.

Unfortunately, the references to Myanmar in this week’s communique do not appear to represent much of a step forward for the bloc; nor, arguably, do they match the seriousness of the country’s crisis, which the United Nations claims has now displaced 2.6 million people – or around 5 percent of the population.

First, the bloc “strongly condemned the continued acts of violence against civilians and public facilities and called for immediate cessation, and urged all parties involved to take concrete action to immediately halt indiscriminate violence.” It also referenced the urgent humanitarian crisis in Myanmar, and called for “all relevant parties in Myanmar to ensure the safe and transparent delivery of humanitarian assistance to the people in Myanmar without discrimination.”

As expected, the communique “reaffirmed” ASEAN’s support for its Five-Point Consensus peace plan, which it said remained the bloc’s “main reference to address the political crisis in Myanmar.” (The Consensus, agreed in April 2021, calls for an immediate cessation of violence and political talks involving “all parties” to the country’s conflict, in addition to the provision of humanitarian aid.) It added that it was confident in the resolve of its special envoy, Alounkeo Kittikhoun of the Lao Ministry of Foreign Affairs, to achieve “an inclusive and durable peaceful resolution” to the conflict.

All told, the communique’s paragraphs on Myanmar reflect an organization that is bereft of ideas on how to deal with its problem member within the tight confines of its norms of consensus-based decision-making and “non-interference” in the internal affairs of member states. Since the establishment of the Five-Point Consensus, the military junta has done nearly nothing to implement its most meaningful elements. For this inaction, the most that ASEAN’s member states have been able to do so far is to block Myanmar from sending political representatives to the bloc’s summits and high-level meetings. (This week in Laos, it was represented by Aung Kyaw Moe, the permanent secretary of the junta’s Foreign Ministry.)

The section on Myanmar also included a curious reference in which the bloc’s ministers “reaffirmed the relevant Leaders’ decisions,” without specifying what leaders, or what decisions, this referred to. This may have been a reference to reports that ASEAN has agreed to allow Thailand to take on a broader role, as Thai Foreign Minister Maris Sangiampongsa said over the weekend. Thailand, which shares a long border with Myanmar, has already taken a prominent role in the bloc’s provision of cross-border humanitarian assistance. One former ambassador also questioned whether the phrase might signal a “confirmation that individual leaders can do as they please” on Myanmar’s conflict.

In any event, as the conflict spreads, and ethnic armed groups and People’s Defense Forces opposed to the military regime gain ground across the country, the Five-Point Consensus, which was established before the protests against the coup regime had evolved into a nationwide armed uprising, bears increasingly little resemblance to the political realities inside the country.

Recognizing the extent of the crisis, ASEAN has not been inactive. Last year, it set up a “troika” mechanism, including the bloc’s past, present, and future chairs, in order to coordinate its approach and ensure consistency between chairmanships. But there is little value in consistency on a policy that is so out of step with the situation in Myanmar.

In a statement following Saturday’s meetings, the National Unity Government (NUG), which is coordinating the nationwide uprising against the military junta, made exactly this point. While expressing gratitude for ASEAN’s continuing engagement on Myanmar’s conflict, it pointed to the expanding territorial control of the NUG and its partners, and the unwillingness of the military to implement the most important elements of the Five-Point Consensus as solid grounds for a “comprehensive review” of the peace plan.

Specifically, it made five demands of ASEAN member states: to “engage directly with the NUG and its ethnic and civil society partners as the legitimate representatives of Myanmar and its people”; to increase pressure, including targeted sanctions, on the junta; to protect refugees; to facilitate cross-border humanitarian aid, “including through ethnic and civil society channels, and bypassing the junta’s obstructions”; and to “seek international support” for the implementation of the Five-Point Consensus from “external partners and the international community.”

It is wishful thinking that ASEAN will heed any of these points, particularly the NUG’s admonition to treat it and Myanmar civil society as the “legitimate representatives” of the Myanmar people. But the NUG is most certainly a major player in the conflict, one that ASEAN should engage directly, and, as Thiha Wint Aung, Jaivet Ealom, and Mehek Berry argued in these pages last week, “in an official capacity.”

This would, of course, be entirely consistent with the Five-Point Consensus, which calls for political, dialogue involving “all parties” to the conflict. Two main parties now claim to be the legitimate government of Myanmar; both need to be recognized if ASEAN has any claim to be advancing political dialogue, however remote the prospect of a final resolution.

While ASEAN has been rightly criticized for its approach to the crisis in Myanmar, the zero-sum nature of the conflict and the evident lack of appetite for negotiations on both sides make it unlikely that any outside actor can facilitate a swift or lasting resolution. Even so, ASEAN “has shown itself to be unable even to come up with a realistic strategy or approach to the issue,” Scot Marciel, a former U.S. ambassador to Myanmar, wrote on the social media network X over the weekend.

This is something that some member states have recognized for some time. Speaking to reporters in Vientiane last week after a meeting of the Indonesia-Laos-Malaysia troika, Malaysian Foreign Minister Mohamad Hasan said that “engagement with all parties involved is necessary because in Myanmar, it’s not just the junta; there are many parties, especially those seeking independence and others.”

The problem is that despite a change of government and approach in Thailand, the bloc remains divided on how far to push Myanmar’s military, and whether a more active policy – for instance, one that involves direct engagement with the NUG – would trip across the line into “interference” in Myanmar’s internal affairs. Given that there is little likelihood of a breakthrough on this front, ASEAN will continue to react to events in Myanmar rather than playing a role in directing them, to however insignificant a degree.