Last month, Thailand completed the complex process of choosing a new set of senators to replace the military-appointed senators in the upper house. Because the Senate is an influential force in Thai politics, the selection has been scrutinized by both domestic and foreign media. The selection process has been variously dubbed the “definition of insanity,” “strange and undemocratic,” and “the most complicated elections in the world,” reflecting the highly complicated selection processes and the lack of transparency of the Election Commission (EC) in monitoring the process. As many pundits have noted, the rules governing the selection of senators privilege older, wealthier, and better-connected individuals, and is akin to an election within an exclusive club that simply conserves the status quo. While it is partly true that the new senators can make progressive reforms difficult, an analysis that only focuses on the institutional rules of how Senators are selected tend to neglect how civil society actors work in and around these roles – especially the younger generation on the ground.

Thailand’s Senate System at a Glance

Thailand has a bicameral parliament, including a lower house (the House of Representatives) and an upper house (the Senate). The lower house, which had its election last year, forms the government, while the senate plays a more oversight role, such as having the power to veto constitutional amendments, and provides an additional check on the government’s power. Unlike the House of Representatives, the Senate is not meant to directly represent “the people” but rather two key groups: important professions who can provide non-partisan expert opinion and social identity groups, especially minority groups.

In principle, the Senate is supposed to provide a bulwark against populism and the “tyranny of the majority,” where the majority’s preferences might harm the minority. However, achieving the right balance of power between the two chambers can be challenging. After Thailand’s last military coup in 2014, the Senate was granted an outsized amount of power, to the point that it could even block the leading prime ministerial candidate from taking power at last year’s general election. While the new Senate will no longer be able to participate in the prime ministerial vote, it still retains substantial power. This includes appointing candidates to the much-criticized EC, Constitutional Court, and National Anti-Corruption Commission (each notoriously known for thwarting political reforms in Thailand) and can veto constitutional amendment proposals – a subject that has been hotly debated in Thailand as the military controversially drew up the current constitution. This enables the Senate to even legally appoint someone who has not been elected as a Member of Parliament to become prime minister.

How are senators selected? There are 200 seats in 20 categories, representing professional and social identity groups. Only senatorial candidates can vote for other candidates (including themselves) to become Senators. To be eligible as a candidate (and thus be eligible to vote for senatorial candidates), they are required to be at least 40 years old and possess a minimum of 10 years of knowledge and experience in their field, though the criteria for proving such expertise remain unclear.

The rationale behind only having senatorial candidates be eligible to vote among themselves, especially from different expertise or social identity groups is partly to insulate the Senate from politics or vote-buying. However, if the goal is to provide an apolitical, meritocratic basis for selecting senators, it is highly doubtful that senatorial candidates in one field (e.g. education) could effectively judge and select “qualified” senatorial candidates from other fields (e.g. rice farming). This was exacerbated when the EC restricted candidates from running public campaigns. Unsurprisingly, the system was seen as an election among an exclusive club of senior, wealthy, and well-connected individuals. Many candidates did not even possess clear expertise, but were selected precisely because they were known outside their own profession.

The Role of the Youth Organizers

Focusing too much on the institutional rules, however, one can miss the fact that young people played a non-trivial role in the selection process. One of the most prominent actors was a network of civil society groups called “Senate67,” an ad-hoc collaboration among Thai civil society groups and civic-tech organizations (such as iLaw, We Watch, and WeVis, to name a few). Although most members were not eligible to be candidates due to their age, the group was formed in April this year precisely to increase public participation and ensure the transparency of the senatorial selection process.

“Run to Vote”

One way that Senate67 preempted the exclusionary aspects of the senatorial selection process was to launch a campaign called “Run to Vote.” This campaign encouraged any qualified Thai citizens to run in the Senate race regardless of their genuine intention of becoming a senator. The hope was that a high number of candidates would mitigate potential corruption of the process in two ways. First, the more people apply as senatorial candidates, the more voters there are, and thus the more difficult it becomes for a malignant candidate to buy off votes of fellow senatorial candidates.

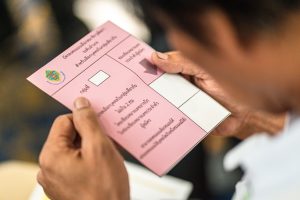

Candidates take part in mock elections that detail how votes are to be counted. (Photo: iLaw TH)

Second, unlike popular elections where the public can observe the vote counting at voting stations, the EC allowed only senatorial candidates (or those who had submitted a request and been approved in advance by the EC) to observe the vote-counting process. Thus, more people registered as candidates means more watchful eyes to increase the transparency of a process otherwise designed to be exclusive.

To further encourage eligible people to join the race, Senate67 made it as easy as possible for people to register as senatorial candidates. While the process of registering as a senatorial candidate is notoriously complicated and full of legalistic detail, Senate67 provided digestible information related to the Senate selection to the public via its website and through public events.

Facilitating Informed Voting

Even with more everyday Thais registering as senatorial candidates, this still does not mitigate the problem that candidates may not know enough about each other to assess who they wish to vote for. It also would remain a highly opaque process out of the public view.

Senate67 addressed this by bringing senatorial candidates into the public. It did so by organizing public events where candidates could introduce themselves to each other and state their positions on important debated issues, such as whether they support changing the constitution, whether they agree to have a new set of constitution drafters, whether they support abolishing the Senate, whether they agree to grant amnesty to all political prisoners, and to what extent they agree to abolish compulsory military conscription, among others.

Senate67 also helped candidates learn about each other’s backgrounds on their website. They encouraged candidates to voluntarily and publicly present their profiles on the Senate67 website, allowing candidates to browse each other’s information at any time. The events also featured voting simulations to give candidates experience and help them identify potential difficulties and confusion that could occur during the actual voting. In the two months in the run-up to the actual selections, Senate67 organized more than 60 public activities across 40 provinces.

These efforts were not only meant to help candidates make more informed voting decisions but also to make them accountable to the public. These issues are highly likely to be debated in parliament and will require Senators to vote for or against them in the future. By having their positions in the public, the group staked a reference point that would encourage candidates to adhere to the positions they had announced.

A Futile Effort?

The composition of the new Senate suggests that any radical political changes, such as amending the whole of the military constitution, are highly unlikely to take place in Thailand. This is because the majority of the selected senators are affiliated with political parties that support the conservative establishment. While they are largely old, wealthy, and well-connected elites, this does not mean that the efforts of the younger generation, such as those of Senate67, were futile.

One of the newly selected senators, who witnessed the entire selection process firsthand, told me that the younger generation of Senate67 made a concrete contribution to a “cleaner” selection process. They consistently monitored the proceedings, identified problematic areas prone to corruption, informed the public, and called for the Election Commission to be more transparent in terms of score announcements. He said, “Given the rigged rules and potential for high corruption at any stage of the process, they helped the system as best as could have been hoped for. Without them, there is no doubt that the outcome would have been much worse.”

Despite the hurdles, a total of 45,754 candidates registered for the Senate race. The senator also suggested that although it is difficult to know precisely why candidates registered for the race, it is undeniable that Senate67’s campaign inspired many people to enroll. Many of these candidates were from civil society groups that often received information from and had worked with the organizations forming Senate67. While no one can predict the future of Thai politics, the new batch of senators includes a few individuals from civil society and non-establishment groups, opening the possibility for progressive change. This prospect for change is at least better than the previous set approved by the military government and suggests more than simply perpetuating the status quo, as the main narratives often portray.

This article was originally published under the Rising Powers Initiative. The views expressed are strictly the author’s own.