Several Indian media outlets, including the Economic Times, The Print, and NDTV, have printed what is purportedly a speech that Bangladesh’s former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina planned to make – but which she was unable to deliver before hastily leaving the country on August 5.

It does not come as a surprise that in the undelivered speech, which Hasina recently discussed with her close associates in India, she made significant accusations against the United States, claiming that it orchestrated the plan to remove her from power.

“I resigned so that I did not have to see the procession of dead bodies. They wanted to come to power over the dead bodies of students, but I did not allow it. I resigned from [the] premiership,” Hasina was quoted as saying.

“I could have remained in power if I had surrendered the sovereignty of Saint Martin Island and allowed America to hold sway over the Bay of Bengal. I beseech to the people of my land, please do not be manipulated by radicals,” Hasina was reportedly set to say in her undelivered speech.

Her son, Sajeeb Wazed Joy, denied the accuracy of the Indian media reports, saying on X (formerly Twitter): “The recent resignation statement attributed to my mother published in a newspaper is completely false and fabricated.”

However, Joy himself has pointed the finger at unidentified foreign forces for forcing his mother from office, telling media that the protests were stoked “from beyond Bangladesh.” He did not provide evidence for the claim or specify which country he believed had been involved.

Notably, Hasina has long blamed the United States for attempting to unseat her. In April last year, while speaking in the Bangladesh Parliament, she went so far as to say, “The U.S. can overthrow the government in any country, particularly Muslim countries.”

She was speaking at a time when then-Foreign Minister of Bangladesh Dr. AK Abdul Momen was visiting Washington, D.C., which speaks volumes about the kind of relationship Hasina maintained with Washington in recent years.

Each time the United States opposed her government on any front, Hasina interpreted it as a sign of an attempt to oust her from power.

Following the controversial January 7 elections, which were marked by low voter turnout and a boycott from the main opposition, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the U.S. government said that the polls were neither free nor fair. The U.S. State Department expressed concerns over reports of voting irregularities, condemned the violence that took place, and lamented the lack of participation of all political parties.

Even earlier, in November 2023, tensions between Bangladesh and the United States escalated, drawing international attention.

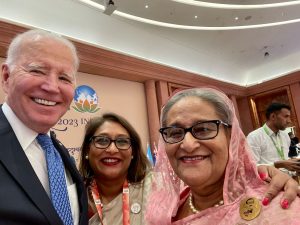

At that time, Hasina and the U.S. President Joe Biden were involved in a public dispute following large-scale protests in Bangladesh.

Opposition parties, clearly dissatisfied with the status quo, demanded Hasina’s resignation and the formation of a caretaker government to ensure fair elections in January. Hasina’s refusal to step down, naturally, led to a standoff.

The U.S. ambassador in Dhaka later met with Bangladesh’s chief election commissioner to emphasize the importance of transparent elections and to urge dialogue among all political parties.

Later, during a press conference, Hasina likened the ambassador’s call for dialogue with the opposition to a hypothetical scenario where Biden would sit down for talks with his political rival, former President Donald Trump.

But the starting point of the tension between Bangladesh and the United States – which now seems to have reached its peak – came even earlier, in 2021, when the world was still grappling with the coronavirus pandemic.

On December 10, 2021, the U.S. Treasury Department imposed sanctions on the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) and several of its former officials. The sanctions were a response to allegations of serious human rights abuses committed by the RAB, a specialized anti-crime and anti-terrorism unit in Bangladesh. The United States accused the unit of involvement in extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and other forms of violence.

This move did not go down well with Hasina’s government, which vehemently criticized the sanctions as interference in its internal affairs and unjustly targeted its security forces.

Just under two years later, in September 2023, the U.S. State Department warned that it would “impose visa restrictions on Bangladeshi individuals responsible for, or complicit in, undermining the democratic election process in Bangladesh,” including “members of law enforcement, the ruling party, and the political opposition.”

Explaining the visa restrictions, the State Department said, “The United States is committed to supporting free and fair elections in Bangladesh that are carried out in a peaceful manner.”

Again, Hasina hit back, denying there were any issues of concern with Bangladesh’s election process and questions why the United States would “suddenly want to impose visa restrictions.”

On May 21 of this year, the U.S. State Department enacted visa restrictions on former Bangladesh army chief Gen. (Retd) Aziz Ahmed, accusing him of “involvement in significant corruption” and “undermining… Bangladesh’s democratic institutions.” He became the first Bangladeshi national to be publicly sanctioned in this manner by the U.S. administration.

Most recently, the frozen relationship between Hasina and the United States grew even more apparent when the U.S. State Department, on July 22, in the thick of the student-led protest movement, urged the Awami League government to “uphold the right to peaceful protest.”

U.S. State Department Spokesperson Mathew Miller stated, “We condemn any violence against peaceful protesters.”

At the time, Bangladesh, a country of 180 million people, was going through an unprecedented internet blackout aimed at not only suppressing free speech but curbing any sort of communication.

While the United States continued advocating for the basic rights of Bangladeshis, Hasina and her government kept on accusing Washington of one plot after another.

In May of this year, during a 14-party meeting at the Ganabhaban, the official residence of Bangladesh’s prime minister, Hasina made a shocking accusation about a purported plot to create a “Christian state like East Timor” using territory from Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Though she did not disclose at the time which country was referring to, it was all but apparent that she was actually talking about the United States.

During that meeting, she mentioned a proposal from “a white man” to build an airbase in Bangladesh for a particular “foreign country.” In return, Hasina said, she would receive guaranteed support for a smooth re-election in the January 7 polls.

The conversation surrounding Saint Martin’s Island, located in the northeastern part of Bay of Bengal, is also nothing new.

In a press conference at Ganabhaban in January last year, Hasina claimed that her party, the Awami League, did not seek to come to power by selling any national resources. In contrast, she alleged that the opposition BNP wanted to gain power by promising to sell Saint Martin’s Island.

“The BNP came to power in 2001 by giving an undertaking to sell gas. Now they want to sell the country. They want to come to power by selling Saint Martin’s Island,” Hasina said.

The United States, however, has always declined such claims. Miller, the State Department spokesperson, asserted in June last year that the United States has never engaged in any discussions regarding taking control of the island, nor had any intention to do so.

It was also widely speculated that the United States sought Saint Martin’s Island to build an air base and that Bangladesh’s potential participation in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) – a strategic Indo-Pacific alliance consisting of Australia, India, Japan, and the United States – was a factor in this interest.

Michael Kugelman, the deputy director and senior associate for South Asia at the Washington-based Wilson Center, claimed otherwise in an interview with the Bangladeshi daily The Daily Star in March 2022.

“I can’t imagine the U.S. wants or expects Bangladesh to join the Quad. There are presently no plans to expand the number of Quad members,” he said.

U.S. rivals have taken careful note of the accusations emanating from Bangladesh. On December 15, 2023, Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova predicted at a press briefing that if Sheikh Hasina were to come to power in the upcoming election, the United States would use all its resources to overthrow her government.

“Key industries may come under attack, as well as a number of officials who will be accused without evidence of obstructing the democratic will of citizens in the upcoming parliamentary elections on January 7, 2024,” Zakharova said.

“If the results of the people’s will are not satisfactory to the United States, attempts to further destabilize the situation in Bangladesh along the lines of the ‘Arab Spring’ are likely,” she added.

The U.S. State Department refrained from responding to Russia’s allegations at the time, having previously denied any interference in Bangladesh’s internal affairs on several occasions.

Bangladesh’s then-Foreign Minister Momen also dismissed the possibility of an Arab Spring-like situation in Bangladesh, denouncing the remarks made by Zakharova.

“‘Friendship to all, malice to none’ is the foundation of the foreign policy of Bangladesh,” said Momen. “It is not our headache whoever says what. We don’t want to be dragged into the tension among superpowers. We want to go ahead with our balanced foreign policy.”

“I don’t really think there is such an opportunity,” Momen added.