Recent reports indicate good reasons to be optimistic about the future of the Philippine economy. The Philippine Development Plan 2023-2028 assumes an annual growth rate of 6.5 to 8 percent for 2024-2028. The country registered growth of more than 6 percent for a few years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, which many think can be repeated and sustained. The country has a promising tourism sector, and many on-going infrastructure projects, including the renovation of Manila’s international airport. Wages are increasing, unemployment and underemployment are down, the dependency ratio is expected to continue declining until 2035, and the middle class is growing. For a country that struggled for decades, all this is good news.

Yet, projections about the Philippine economy are overly optimistic. The country will certainly continue growing, and the overall situation will improve, though much more slowly than many think. Optimistic projections about developing countries tend to be based on simple extrapolations that hardly ever materialize. In the case of the Philippines, overoptimism also seems to ignore a number of important structural issues that need to be addressed if the country is to maintain a high growth rate and catch up with its neighbors.

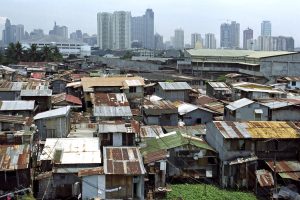

The Philippines is still a lower middle-income country with a Gross National Income (GNI) per capita just above $4,000. It is about to attain upper middle-income status. The ratio of Philippine to U.S. income per capita has remained flat at about 5 percent since 1970 (see Figure 1). The same ratio with respect to its regional neighbors Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and China, shows a downward trend. All these nations have a higher per capita income than the Philippines today (see Figure 2). The case of Vietnam is particularly telling: in the early 1990s, Philippine income per capita was about eight times that of Vietnam. Today, it is lower (see Figure 3).

Likewise, recent work by the Oxford economist Lant Pritchett showed that in 2018, the Philippines’ per capita income was below that of the world’s leading economies in 1918.

All this means that past growth rates were low. The Philippines has to grow a lot and for a long time if it wants to increase significantly its income per capita and catch up with its neighbors. Yet, we cannot expect the country to attain an annual growth rate of 7 percent during the coming decades. We know that since the 1950s, average world growth has been 2 percent with a standard deviation of 2 percent. Therefore, a growth rate of 6 percent or above would be an extraordinary tail event.

We also know that accelerations to spectacularly rapid, extended periods of growth are rare. Episodes of super-rapid growth (above 6 percent) tend to be extremely short-lived. Only China, followed by South Korea and Taiwan, have been able to attain this rate of growth and maintain it for two decades or longer. Most developing countries tend to see “boom and bust” growth – that is, periods of growth acceleration followed by periods of deceleration. Moreover, the fundamental characteristic about the growth rates of many countries over the medium run is non-persistent growth with episodes of boom, stagnation, and bust, that is, economic volatility. Circumstances or policies that produce 10 years of rapid economic growth can be easily reversed, often leaving countries no better off than they were prior to the expansion.

History shows that today’s high-income economies underwent a process of economic transformation, where workers left agriculture and found jobs in activities of higher productivity and that paid higher wages, especially in manufacturing. The manufacturing sector itself underwent transformation in the direction of producing more complex products in clusters like automobiles, electronics, pharmaceuticals, or chemicals. South Korea’s policymakers and companies understood this well. They also understood that they had to export. This served a double purpose. First, it subjected the companies to competition. Second, it helped relax the balance-of-payments constraint.

In the case of the Philippines, employment in manufacturing has never represented more than 12 percent of total employment, well below that share in countries that have progressed to high income status, in which at least 20 percent of workers were employed in the manufacturing sector; in many, it was above 30 percent. Instead of pursuing industrialization, the Philippines went into services of low productivity. Today, about 22 percent of its workers are employed in retail and wholesale trade, a service sector of very low productivity and wages.

Moreover, about 23 percent of its workers are employed in agriculture, and another 9 percent in construction, both also low-productivity activities. This employment structure lies behind the country’s low wages and income per capita. On top of it, the country does not have top exporting companies that compete in the world economy. 80 percent of Philippine workers earn at most 15,000 pesos a month (less than $300 a month), and about 2 million Filipino workers are abroad sending vital remittances.

Additionally, a number of inherited policies have hampered the Philippines’ economic transformation. Among those are post-colonial policies that rewarded the export of unprocessed agricultural products as opposed to value-added manufactured goods. For example, the Bell Trade Act of 1946, stipulated that war reparation payments would be tied to U.S. preferential access to Philippine markets. Under the terms of the Act, the U.S. imported from the Philippines raw agricultural products such as sugar and pineapples, and then exported finished food products and other goods to the Philippines with low tariffs.

The Act also established that the Philippines currency had to be pegged to the U.S. dollar, with any changes having to be pre-approved by the U.S. president. This caused the overvaluation of the peso and made Philippine exports less competitive and dashed the possibility of creating a robust manufacturing sector.

To make matters worse, American businesses had priority in accessing foreign reserves. This eventually stoked anti-colonial sentiment and resulted in an amendment of the Bell Trade Act under the Laurel-Langley Agreement in 1955. This memory left its mark on the 1987 constitution, drafted after the ouster of President Ferdinand Marcos Sr., which included the “Filipino First and Filipino Only” clause (which dates back to the 1950s with President Garcia). This gives Filipinos preferential treatment in the national economy over foreigners. The unintended consequence was to limit the sectors available to foreign investors, and the local capture of business ventures by a few uncompetitive oligarchs. This constitutional provision remains in place today.

Under these circumstances, industrialization became a chimera. Today, most Philippine manufacturing companies are small, and the large conglomerates are mostly involved in non-tradable activities such as real estate or banking. There is nothing wrong with these activities except that no single Filipino conglomerate is a significant competitor in world markets. Using the De La Salle econometric model of the Philippine economy, we have shown that the Philippines will not attain the 2028 income per capita target set out in the Philippine Development Plan. It will also fail to attain the poverty incidence rate targeted. We have simulated the effect of a significant increase in the share of employment in manufacturing (however unlikely). This is the only way to become an upper middle-income economy and show significant progress, much faster than it will otherwise happen.

In his latest State of the Nation Address on July 22, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. painted a rosy picture of the Philippine economy. While we believe that the Philippines will continue progressing and improving, we also believe that it will grow at a slower pace than that claimed by the administration. The lack of focus on what really matters (industrialization, firms, exports) will continue taking the country down the same MOTS (“More of the Same”) path it has traversed for decades and that has delivered so little. A country that never industrialized, that needs to import products that a “normal” country should manufacture (virtually everything you see around you), whose companies hardly export and hence do not compete in the world economy, and where half of its workers are engaged in activities of very low productivity, cannot seriously think that its future lies in Artificial Intelligence. Yet, that’s what seems to transpire from speeches by members of the administration. A sense of reality would do wonders.

To sum things up, no doubt the Philippines will continue growing (though it will be hit by periodic crises), but unless its policymakers understand that the country’s firms need to manufacture complex products and export to compete in the world economy, Filipino incomes will continue increasing at a snail’s pace. Constitutional policies that shield conglomerates from competition need to be revised. Sectors that innovate must be open to foreign investment.

Additionally, the government needs to become a forceful driver of the economic transformation that the country needs, and lead a thorough industrialization drive. Filipino firms need to manufacture and compete in the world economy by producing high-quality products, not simple agriculture and basic manufactures. This is what will make wages rise. The Philippines certainly needs infrastructure. Yet, an airport or two will not be a game changer.