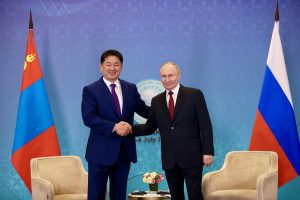

On September 3, Mongolia is set to test Thucydides’ famous observation that the “strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” According to the Kremlin, Russian President Vladimir Putin is scheduled to visit Mongolia to honor the 85th anniversary of the Mongolia-Russia joint victory on the Khalkhin Gol River against Imperial Japan in 1939.

The visit is notable because, in March 2023, the International Criminal Court (ICC) issued an arrest warrant against Putin following the war in Ukraine, accusing him of the war crimes of unlawful deportation and transportation of children in the occupied territory of Ukraine. Putin is the first head of a permanent member state in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to get an arrest warrant from the ICC.

Mongolia, as a member of the ICC and a signatory of the Rome Statute, is supposed to honor ICC’s arrest warrants. But it is unlikely that Putin will get arrested in Mongolian territory, as Mongolia continues to depend heavily on Russian energy.

In an ideal world, ICC member countries are obliged to detain a court suspect under the Rome Statute; however, the court itself has no enforcement mechanism over sovereign states. It is up to the states whether they want to cooperate with the ICC. The infamous case of Sudanese dictator Omar Al-Bashir’s visit to South Africa in 2015 sparked anger and debate as South Africa, an ICC member country, failed to fulfill its obligation to the international community.

Notably, South Africa avoided repeating the controversy by having Putin stay away from the BRICS summit in Johannesburg last year. The Russian leader had to attend virtually after South Africa repeatedly lobbied him not to attend.

Now Mongolia will have the dubious honor of being the first ICC member state to openly defy the court’s arrest warrant for Putin.

For Ulaanbaatar, the stakes are high. Mongolia’s energy security is deeply tied to its neighbors. Russia is the source for 95 percent of its petroleum products, which account for 35 percent of all imports in Mongolia. Mongolia’s export-led economy, which is driven by raw material sales such as coal, copper, and gold, is highly reliant on Russian fuel as a means of transport to China. Furthermore, average Mongolians are very much used to fuel shortages as Moscow maneuvers its leverage whenever it is convenient.

As the Russian war in Ukraine rages, causing death or severe injury to more than half a million people thus far, both sides are strategically targeting critical energy infrastructure, including oil refineries. The Energy Ministry of Russia reported a ban on fuel exports, including gasoline, starting March 1, 2024, citing saturation of the domestic market and maintenance. However, Moscow made exceptions for a few friendly countries – including Mongolia.

Even though the Mongolian government brands itself as a beacon of democracy in the heart of Asia between its authoritarian counterparts, it is nevertheless caught in the reality of geopolitics. Mongolia will likely disregard its obligation to arrest Vladimir Putin under the Rome Statute and instead sign another agreement on fuel supply from Russia that serves its national interest.

This choice is a huge disappointment to the international community and any believer in the rules-based system; however, in the real world, a state must put its national interest over international obligation. And that includes energy security. The question is, what kind of language will Ulaanbaatar use to defend its move to invite Putin in the midst of the Russia-Ukraine war?