Violence erupted in Bangladesh’s southeastern district of Khagrachari on the evening of September 19, as tensions between Bengali settlers and members of the Indigenous community in the sensitive Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) region boiled over, resulting in the death of at least three people and destruction of numerous Indigenous homes and businesses.

The CHT region has a deep-rooted history of conflict, beginning with British colonial policies that promoted Bengali settlement in the hills. This resulted in the displacement and marginalization of Indigenous communities. Later, successive Bangladeshi governments adopted assimilationist policies, which intensified resentment and distrust in this sparsely populated hilly region of Bangladesh.

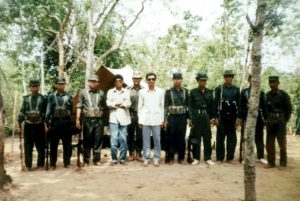

A decade-long insurgency wracked the CHT and the region continues to suffer its after-effects. It has witnessed countless political, ethnic, and petty murders.

The recent unrest was ignited by the death of Md Mamun, a Bengali man. He was killed by a mob largely made up of ethnic Chakma and Marma individuals following allegations of motorcycle theft.

Bengali settlers then organized a protest march. The situation was exacerbated by a false announcement from a local mosque that incited a violent backlash against the Indigenous community and their properties.

As violence unfolded, many Indigenous residents sought refuge in the forests, helplessly watching their homes and businesses burn. According to Ramsung Marma, a grocery store owner, there was extensive destruction. He told The Diplomat that his shop was among many others destroyed in the town.

Dharma Joyti Chakma, a former chairman of an upazila (an upazila is the lowest administrative division of government in Bangladesh) and Superintendent of Police Md Arefin Jewel confirmed the attacks. They said that the situation remains volatile and could escalate into broader violence if further provocations occur. Both emphasized that, despite increased security measures, deep-seated mistrust persists between Bengali settlers and Indigenous communities.

Long-standing Discontent

The recent attacks in the CHT are not isolated incidents, but rather part of a long-standing pattern of violence and discrimination against Indigenous communities, stemming from deliberate policies of demographic change.

From 1979 to 1983, then-President General Ziaur Rahman resettled over 500,000 Muslim settlers in the CHT to reduce the concentration of the Indigenous population. As a result of such efforts to alter the CHT’s demographic composition, today, these settlers constitute more than 50 percent of the CHT’s population, leading to ongoing tensions.

The Indigenous people of the CHT have long sought autonomy and the preservation of their culture, fearing that the growing number of Bengali settlers threatens to erode their cultural heritage.

Rights activist Pallab Chakma told The Diplomat that the Indigenous communities in the CHT possess unique cultures, languages, and traditions. He noted that the arrival of Bengali settlers “has endangered their cultural heritage and identity, resulting in tensions regarding land use and cultural preservation.”

Additionally, Chakma emphasized that land disputes are a significant source of conflict. “Indigenous people assert ancestral rights to the land, while the government has issued land titles to Bengali settlers. This has led to extensive land grabbing and the displacement of Indigenous communities,” he explained.

Another contentious issue is the extensive control exercised by the armed forces of Bangladesh in the CHT region. Many believe that the military’s presence in the CHT goes beyond peacekeeping and reflects a long history of state control. This power dynamic fosters a sense of vulnerability and mistrust among the Indigenous people, who often perceive the army as an oppressive force rather than a protective one.

In the latest unrest, eyewitnesses also reported that the army did not intervene to quell the violence. Indeed, some alleged that the military supported the settlers. This inaction has drawn criticism, especially given the army’s recently granted magisterial powers.

Debate Surrounding the Armed Forces’ Presence

“The claim that the army’s actions in the CHT were necessary for maintaining national unity is fundamentally flawed,” said Amalesh Tripura, a CHT rights activist, in an interview with The Diplomat. “It overlooks the ongoing suffering of Indigenous people and the continuous reports of violence and oppression,” he said, adding that the military’s conduct resembles an abusive dynamic, using power to suppress legitimate calls for autonomy and cultural preservation.

Zobaida Nasreen, a researcher at Hiroshima University who specializes in CHT issues, echoed these sentiments, stating that the current situation highlights the broader issue of marginalized groups facing systemic oppression under the guise of national security.

“Successive Bangladeshi governments have viewed the CHT situation through a distorted lens of security concerns,” she explained, “much like how the Indian government views Kashmir solely through a security lens.”

“The CHT Peace Accord was meant to shift this perspective,” she pointed out.

Signed between the Bangladesh government and the Parbatya Chattagram Jana Samhati Samiti (PCJSS), an umbrella political grouping of Chakma organizations and groups, the 1997 Chittagong Hill Tracts Peace Accord aimed to resolve the conflict in the CHT through peaceful and political means. Key provisions included the preservation of the CHT’s unique characteristics, the establishment of a special administrative system with regional and district councils, and the devolution of political, administrative, and economic powers.

“Unfortunately, there is no reflection of the implementation of that peace accord,” Nasreen said, adding that insurgent movements like Shanti Bahini were a direct reaction to discriminatory policies and the forced displacement of Indigenous people.

Where Lies the Solution?

Dr. M. Masum, a professor of economics at Jahangirnagar University in Bangladesh, told The Diplomat that many rights activists tend to blame the armed forces for the ongoing issues in the CHT.

“I believe this perspective is misguided,” Mamun stated, emphasizing the importance of considering the historical context.

Masum noted that most ethnic minorities were not involved in the 1971 Liberation War, which primarily sought self-determination for Bengalis from West Pakistani dominance. Some leaders, such as the Chakma and Bohmong chiefs, collaborated with the Pakistan army.

Consequently, after independence in 1971, the Chakma and Bohmong faced backlash, much like other collaborators, particularly from Bengali families who had lost loved ones during the war.

As tensions grew between the Bengalis and the hill communities, the PCJSS was established in 1972, and its military branch, Shanti Bahini, initiated insurgency operations in 1973, prompting the army’s deployment for national security purposes.

Mamun explained that the porous borders with India and Myanmar facilitated the movement of insurgents, complicating counterinsurgency efforts. “As a result, the army established a significant presence throughout the region, unable to effectively seal the borders,” he added.

Mehedi Hasan Palash, editor of Parbottyo News, a website that focuses on the CHT, told The Diplomat that a historical analysis reveals that none of the major tribes in the CHT was originally indigenous.

“Over time, they migrated and settled alongside Bengalis involved in trade and agriculture,” he explained. “However, in 1900, the British designated the CHT as an ‘excluded’ area to prevent Bengali revolutionaries from finding refuge there, effectively halting natural Bengali migration.”

Palash noted that if this exclusionary policy hadn’t been implemented, the CHT and its inhabitants might have integrated smoothly with the rest of British India, particularly East Bengal, now Bangladesh.

He added that Bengalis make up nearly half of the CHT’s population and emphasized that a solution addressing the aspirations of the ethnic CHT communities without marginalizing the Bengalis could help resolve the ongoing impasse.