In 2004, former U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Strobe Talbott published “Engaging India. Diplomacy, Democracy and the Bomb,” his diplomatic account of U.S. relations with India and Pakistan over nuclear proliferation after both countries tested nuclear weapons in May 1998. In it, Talbott tells the story of extended talks with his main Indian interlocutor, Minister of External Affairs Jaswant Singh. Though Talbott could not achieve key U.S. non-proliferation objectives in the negotiations with Singh, their dialogue contributed to an unprecedented improvement of U.S. relations with India, culminating in President Bill Clinton’s landmark visit in New Delhi in March 2000.

Recently declassified archival sources from Talbott’s State Department papers shine new light on the U.S. engagement with India. Following a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request by the National Security Archive, Talbott’s files were processed and made available in the State Department’s Virtual Reading Room. His materials allow a new glimpse into U.S. diplomacy and should be read in connection with other newly declassified materials and FOIA collections from the Clinton Library, the National Security Archive, and other repositories.

Actually, Talbott’s diplomacy with India started in 1994 when Clinton and Secretary of State Warren Christopher sent him to New Delhi in an effort to overcome the strained bilateral relationship of the Cold War era. Talbott spoke with India’s Prime Minister P.V. Narasimha Rao who was willing to visit Washington in the summer of 1994 in order to work for a new start.

Rao was straightforward in the conversation with Talbott. “I am 73 years old,” Rao said. “I didn’t ask for this job and I don’t need it. The one thing I want to do is to preside over a qualitative improvement in Indo-U.S. relations. Unfortunately, there has never been a sense of affinity between our two democracies. It goes back to John Foster Dulles, who used to call non-alignment immoral, and to Krishna Menon on our side.

“Never mind who is to blame. The fact is that we’ve never lived up to the potential of our relationships.”

However, given the multitude of foreign policy challenges and civil wars in the Balkans, Somalia, and Rwanda, Clinton was not able to devote as much attention to India as he intended. Moreover, India’s refusal to join the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) was an additional strain that prevented the Clinton administration from developing a closer bilateral relationship.

In May 1998, relations grew worse after India’s underground nuclear tests threatened to erode the global non-proliferation regime. The Clinton administration condemned the tests, issued sanctions and undertook a diplomatic effort to defuse the escalation of tensions between India and Pakistan.

A week after India’s test, Clinton and Secretary of State Madeleine Albright sent Talbott to Islamabad and Delhi to manage the crisis. In Islamabad, Talbott spoke with Pakistan’s Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to promise massive financial and military aid and an invitation for a visit in Washington as a reward if Pakistan resisted the temptation to pursue nuclear tests. Although Sharif confessed that “domestic pressure in Pakistan ‘is mounting by the hour,’” he assured Talbott that the government of Pakistan had not yet taken a decision on a potential nuclear test. Talbott warned Pakistan’s Foreign Minister Gohar Ayub Khan that “a Pakistani test would make Pakistan the net loser in its zero-sum game with India.” Despite these efforts from the U.S. diplomat, Pakistan pursued several simultaneous underground nuclear tests on May 28 and 30, 1998.

After the nuclear tests, the Clinton administration sought to convince both India and Pakistan to sign and ratify the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), halt their production of fissile weapons-grade material, and allow for IAEA safeguards on all nuclear facilities. The United States also urged the South Asian rivals to stop missile deployments and flight-testing of ballistic missiles, engage in confidence-building measures, exercise strategic restraint, and enact stricter export controls.

Talbott emphasized that India and Pakistan could not join the NPT as nuclear weapons states (nws) under any circumstances. He thought that “the only way they can join the NPT is as non-nws, as that means pulling a South Africa and renouncing nukes. Short of that, they will have to be kept in a purgatory…”

Talbott anticipated that it would be challenging to achieve these benchmarks given India’s and Pakistan’s insistence to define the scope of their nuclear deterrence requirements. “The Indians are by far the tougher nut to crack because, unlike the Pakistanis, they are resisting any ‘internationalization’ of South Asian security and political issues (except on terms so broad and global as to be meaningless),” he reported.

On the positive side, the government of India acknowledged the urgent need to resume dialogue with the United States to work its way back to a normalization of the relationship, even while retaining its position on the need to pursue nuclear tests.

In June 1998, Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee sent veteran policymaker Jaswant Singh to New York and Washington to explain India’s strategic motives and to assess the situation. While in New York, Singh told journalists that India’s rationale for the nuclear tests was to fill the nuclear security vacuum after the demise of the Soviet Union given what Singh called India’s “exclusion from ‘structural security arrangements’ extended to other parts of the world in the Post-Cold War era.”

Singh explained:

[I]f you examine the stretch from roughly Vancouver to Vladivostok, you have a kind of a nuclear security paradigm that has come into existence through the dissolution of [the] Warsaw Pact. The Asia-Pacific is covered in part. China is an independent nuclear power. It is only Southern Asia and Africa that are out of this protective pattern of security arrangements. Therefore, this, in our assessment and strategic evaluation, is an area uncovered and is a vacuum. If we have the kind of neighborhood that India has, which is extremely troubled, and if we have two declared nuclear weapons powers in our neighborhood, the basic requirement is to acquire a balancing nuclear capability.

On June 4, 1998, Singh repeated this argument in the first meeting with Talbott, pointing out that “virtually every part of the globe was protected by the U.S. nuclear umbrella – the Americas, Europe, East Asia and the Pacific.” By contrast, “India was left in an increasingly threatened South Asia confronted by nuclear powers to its north and west.”

While Talbott emphasized Washington’s uncompromising opposition to India’s nuclear weapons program, he searched for ways to avoid a blame-game about the misunderstandings of the past. Instead, he was determined to find ways forward to restore confidence and to put the bilateral relationship on a new footing.

In this sense, the talks went far beyond the nuclear issue. At one point in their long meeting, Singh rhetorically asked, “[W]hat is holding up a discussion between our two governments? He answered the question himself, saying it was mistrust and disappointment.” Talbott concurred and signaled his willingness to start a strategic dialogue for the long haul.

He summarized the meeting by writing:

[O]ur conversation was frank but without rancor on either side. An extraordinarily thoughtful man, Singh understands the profound crisis in South Asia and in Indo-U.S. relations. He says the PM wants to do something about it. While he defended the GOI’s [government of India’s] point of view, he did not do so tendentiously or arrogantly. Singh would make a credible interlocutor for a senior-level dialogue between U.S. and the GOI.

In July 1998, the first full-fledged delegation session of the India-U.S. dialogue took place at Frankfurt Airport. It did not bring any kind of rapprochement in terms of substance. Despite the absence of movement on the Indian side, Talbott sent Singh a respectful and polite letter writing that “our second [meeting] in Frankfurt provided ample evidence that you and your Prime Minister are making a good-faith and imaginative effort to establish a new modus vivendi between India and the U.S.”

The tone of Talbott’s letter mattered as much as the substance. The primary aim was to meet on an equal footing and to speak with each other directly and candidly. After all, one of the pivotal Indian concerns was that the Clinton administration could rebuff India – which the government of India would take as “a rebuff to ‘an ancient civilization,’” as Singh told Talbott.

When the third meeting in July 1998 also remained inconclusive, Talbott wrote Singh another long letter pointing out ways to overcome the stalemate. Talbott informed Singh about the Clinton administration’s decision to drop its demands for India’s imminent accession to the NPT and the establishment of a flight test ban. In the letter, Talbott set out four essential benchmarks for the establishment of a sustainable non-proliferation regime with India, including a cessation of nuclear testing, a halt in fissile material production, a commitment not to produce further nuclear-capable missiles and aircraft, and the adoption of stricter nuclear export controls.

While the Clinton administration did not give up the long-term aim of a non-nuclear India as a member of the NPT, the strategy was to reach an attainable non-proliferation system for the present. Talbott wrote Singh that “as practitioners of the art of the possible, we would concentrate, in the near term, on the task of agreeing to, and implementing, practical and politically sustainable steps that would serve to reconcile the U.S.’s vital national interest in a viable non-proliferation regime with India’s concept of its own immediate and prospective strategic imperatives.”

However, Singh did not move during the following three rounds of talks. His intransigence was related to India’s domestic politics. The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was expected to suffer defeats in the November 1998 state elections, the Congress Party attacked the BJP for going soft on the CTBT, and nationalists in the BJP tried to undermine Singh.

Moreover, the Vajpayee government lacked consensus over India’s deterrence needs. Speaking confidentially at a private meeting with Talbott in Rome, Singh said that “the Vajpayee government is mired in a combination of stubbornness, resentment, confusion, division and weakness.”

Talbott and Singh agreed that they would wait another year before undertaking a new effort to get the India-U.S. relationship back on track. In the meantime, Singh promised to help establish more effective foreign policy decision-making processes in Delhi, including the establishment of a National Security Council and the adoption of Strategic Defense Review.

On the positive side, Singh’s remarks revealed the trust he had in Talbott. “Had round 7 [of the Singh-Talbott dialogue, held in Rome, Italy] been confined to the full-team plenaries, I would probably have concluded that the road from Rome leads nowhere,” Talbott noted. “However, I had two private sessions with Jaswant [Singh] that indicate there may still be some hope for movement next year.”

Talbott and Singh agreed to convene one more round of talks taking place in New Delhi in late January 1998 in order to draw up a roadmap for the long haul. Talbott was determined to make progress on all four U.S. benchmarks. He wrote Singh:

[W]e can’t settle for less than definitive movement, and soon, on all four benchmarks. I press this point, because, to be frank, I sensed in Rome that there may be a belief on your side that Indian ‘patience,’ or ‘firmness’ will ‘pay off’ by inducing further American ‘concessions’ (you understand why I put all four phrases in quotation marks). In other words, there may be a working assumption on the part of some on your side that we, your American interlocutors, don’t entirely mean what we say about the four legs of the elephant being truly necessary for the animal to walk (at least with us on board); that perhaps the beast can be mobile on two legs (CTBT and export controls).

When Talbott came to New Delhi in late January 1999, he had a chance to convey this message to the entire Indian leadership. Vajpayee argued that India did not want an arms race, but just sought “a credible minimum deterrent.” In turn, Talbott said that India’s restraint would indeed be a precondition for Clinton to visit India, the only major carrot the United States could leverage in return for progress toward the four benchmarks.

At the time, it was not certain whether Clinton would actually visit India, as the Vajpayee government was still stalling. During the first half of 1999, U.S. diplomacy toward India went into a hiatus when NATO went to war in the Balkans and the BJP kept fighting to stay in power in New Delhi.

Things only changed in the summer of 1999 in the context of the Kargil War. Clinton took a tilt toward India after Pakistani troops crossed the demarcation line in Kashmir disguised as Kashmiri militants before taking strategic positions on the Indian side. In July 1999, Clinton forced Pakistan to withdraw its troops and thus contributed to the sea change in India-U.S. relations.

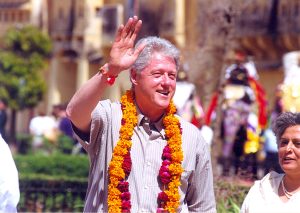

Finally, Clinton visited India in March 2000 with stops in Delhi, Hyderabad, Jaipur, and Mumbai. He was greeted by enormous crowds and got a standing ovation while addressing India’s Parliament.

The United States and India were “no longer estranged democracies. Still, the U.S. did not want to sweep differences under the rug,” Talbott told Singh’s successor, Lalit Mansingh.

In the end, the stalemated nuclear talks contributed to the broadening of India-U.S. relations. Talbott noted that “sometimes a negotiation that fails to resolve a specific dispute can have general and lasting benefits, especially if it is a dialogue in fact as well as in name.”