Taiwan’s political status has served as a point of contention among governments, organizations, and people alike. Companies and celebrities referring to Taiwan as a country have landed in hot water with China, and many have quickly offered apologies and retractions. Government officials largely stick closely to official talking points, similarly walking back any comments that stray too far in either direction. Alternatively, everyday people are welcome to refer to Taiwan however they like, and – to the growing extent that awareness exists in the first place – so too does considerable confusion over its status.

Media organizations thus occupy a difficult position. On one hand, journalists have a responsibility to provide accurate depictions, without bowing to the same concerns that others face. On the other hand, the decision to define Taiwan in any form may feel like a subjective choice, given the ongoing debate over its status. This issue has only become more prominent in recent years amid increased global interest in Taiwan.

This raises an important question: How do different countries’ media organizations define Taiwan?

To pursue this, I compiled roughly 1,500 articles between 2019-2023 from 16 media organizations around the globe, analyzing six nouns (country, nation, democracy, island, territory, and province) and the resulting multi-word terminology, or phrases that include these nouns. In short, my research finds that media references to Taiwan serve as a reflection of countries’ own relations. For countries strongly aligned with either Taiwan or China, for example, outlets define Taiwan through straightforward nouns like simply “country” or “island.”

But what about the United States, whose relationship with Taiwan cannot be adequately described through such simple terms? In this regard, media definitions often adhere to the complexity of Washington’s stance. Journalists do rely heavily on the noun “island” as a starting point, as the ostensibly geographic term constitutes the vast majority of the total nouns encoded by the New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal – extending far beyond typical usage for island nations.

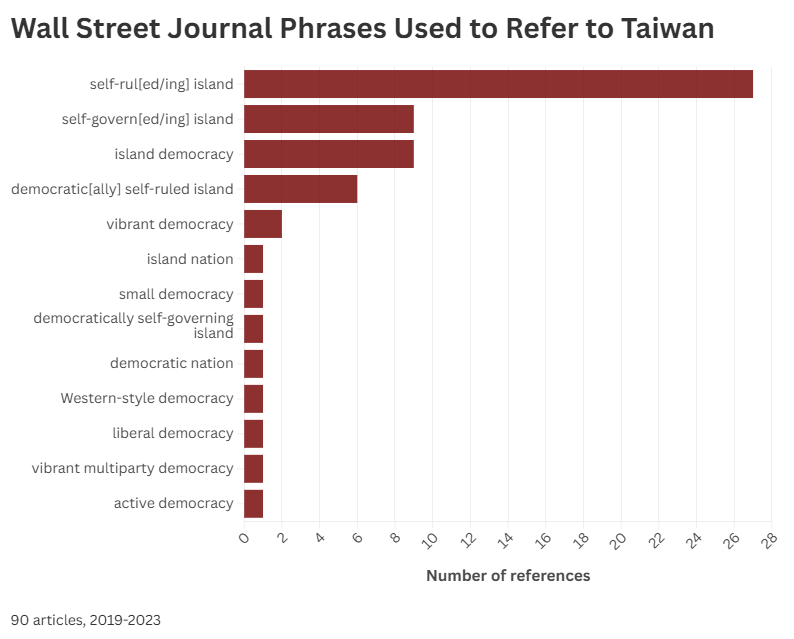

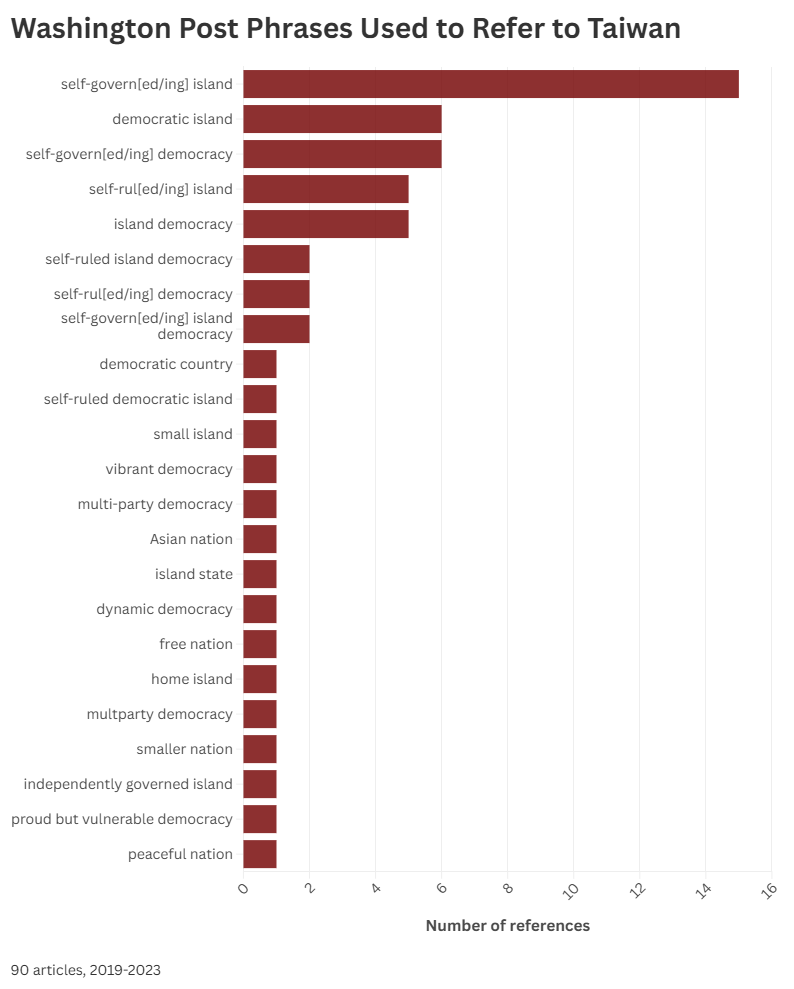

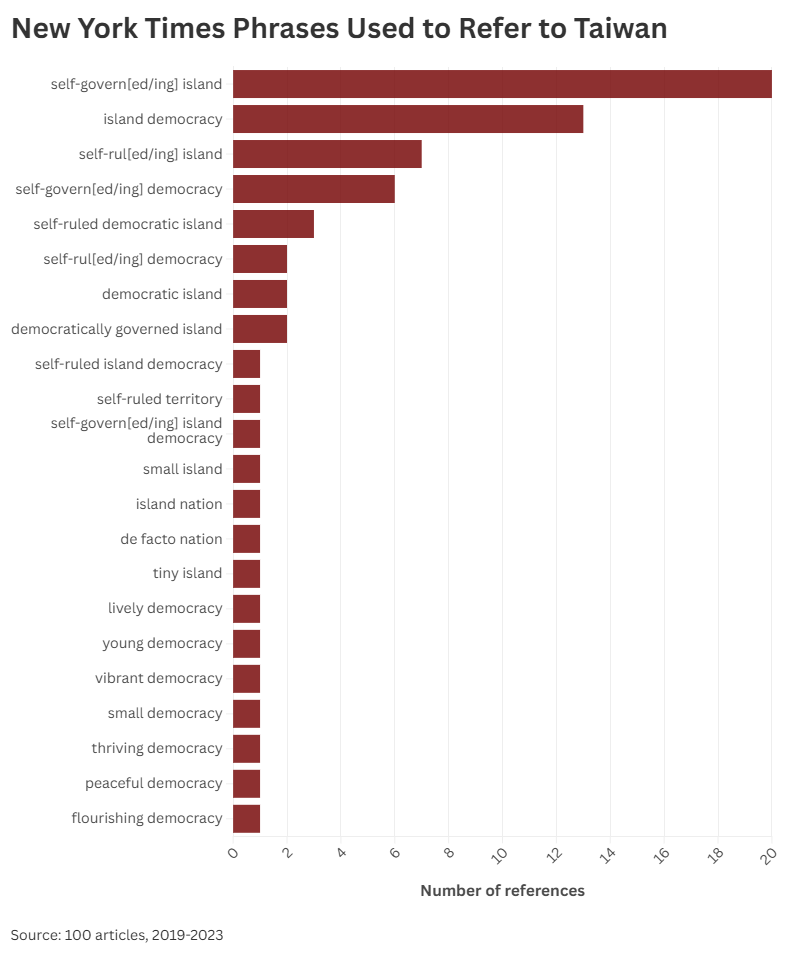

However, these organizations also favor multi-word terminology, which include the noun endings but serve to further define Taiwan in a manner that is largely exclusive to it. All three outlets use either “self-governed” or “self-ruled” island as their preferred phrasing choice. In The Wall Street Journal, for example, the 90 articles sampled included 27 references to Taiwan being a self-ruled island alone, alongside an additional six specifying that it is a “democratic[ally] self-ruled island.”

These distinctions, which are largely unique to Taiwan, serve to amplify and reinforce both its contested status and the sovereign nature of its governance. This is in line with government rhetoric, which often emphasizes Taiwan’s democracy but lacks the terminology that would accompany diplomatic recognition.

In addition, the use of these terms even amid articles that are entirely apolitical indicates a couple points. First, such phrasing is an attempt to contextualize a complex issue for unfamiliar readers. Yet, the most popular noun, island, also serves as a way to avoid making a more straightforward claim of its own. By choosing the noun island, outlets can effectively sidestep the question of Taiwan’s status entirely. One can argue that to avoid defining Taiwan by referring to it as an island is in itself a political choice. But this appears to be a compromise that these three outlets – and many others – readily accept.

This is further evidenced by the second most popular noun choice, “democracy.” Democracy, unlike island, is inherently a political term. But like island, it is used beyond its expected context in articles where the relationship to political themes is tenuous at best. In doing so, outlets can highlight Taiwan’s democratic governance while avoiding staking a more contested claim on its statehood.

Running parallel to this theme is the relatively rare use of the term “country,” which hovered around 10 percent overall and decreased steadily from 2019-2023. Most of the few exceptions came from apolitical topics, indicating that less familiarity breeds greater leeway – or at least that references contained within them are more likely to slip through the editorial cracks.

Others feature political issues that are not strictly geopolitical nonetheless. Consider the following sentence: “In 2019, Taiwan became the first _____ in Asia to legalize same-sex marriage.” Is it difficult to fill in the blank? Many news outlets seemed to think so, with some opting to simply skip over the noun choice entirely. At the same time, this news was a catalyst to define Taiwan in stronger terms for some. There were 18 total country references within the Washington Post’s 90 article sampling, but four of these can be found in the six articles focusing on Taiwan’s marriage equality alone.

While specific topics matter, specific journalists do, too. One foreign policy opinion specialist contributed more than half of the references to Taiwan as a country encoded for a U.S. outlet from 2022-23, despite only writing eight of the 40 sampled articles during this time. Journalists interviewed for this research noted that opinion pieces often offer more space for writers to use their own phrasing, and here, it is likely that the opinion columnist role granted additional leeway.

Finally, different outlets have different standards. As the most popular tabloid newspaper in the U.S., the New York Post serves as a valuable case study. Here, “island” represents a much smaller majority, while “nation” (25 percent) and “country” (17 percent) made up a larger portion in comparison. Moreover, “island nation,” which was only used twice total by the other three outlets, is by far the most common phrasing choice. While others typically defined Taiwan primarily through its geographic status and qualified this definition through political terms, the New York Post was instead significantly more likely to take the opposite approach.

Of course, while my research indicates that these complex media depictions are unique to Taiwan, the next step is delving into why this all matters. A follow-up to this article, the results of a 2,000-person survey utilizing contextual and terminology variations in background information, allows us to do just that by showing how phrasing affects perceptions with respect to foreign policy.