Kharkhorum, the one-time seat of the vast Mongol Empire, was so renowned in its day that travelers from as far away as Europe entered its walls to pay tribute to the Great Khaan Ögödei.

After more than a century of existence, the city was toppled by invading forces, but the Mongols never forgot their ancient capital.

Now Mongolian leaders say they want to build a new city in the valley close to the ancient ruins and make it their new seat of government.

The idea of building a new capital in modern Mongolia is not new – politicians have floated the idea for over a decade – but the current government has recently stepped up efforts to promote the ambitious project.

First, President Khurelsukh Ukhnaa issued an official “Decree on Restoring the Ancient Capital of the Great Mongol Empire” in December 2022. Then he announced the rebuilding of Kharkhorum in an address to the United Nations General Assembly in 2023.

From March to July 2024, an international competition to design the city saw dozens of submissions from across the globe. According to state news agency Monsame, “State administrative bodies of Mongolia, international organizations, and diplomatic missions in Mongolia are planned to be located in New Kharkhorum City.”

Mongolia’s once-and-future capital, Kharkhorum, and the current capital of Ulaanbaatar. Via Google Maps.

Part of the motivation to build a new capital stems from urban problems facing the current one. Ulaanbaatar – where traffic jams can stretch for miles and wintertime air pollution regularly reaches hazardous levels – has grown rapidly in recent decades and the city’s infrastructure has not kept pace with its population growth.

Much of Ulaanbaatar consists of ger districts – unplanned neighborhoods that lack basic infrastructure. There has been an apartment building boom but the sprawl is relentless and has climbed into the surrounding hills.

Rather than undergoing a costly redevelopment of the current capital, Mongolia wants to build another one from scratch on the vast plains of the Orkhon Valley, where Mongol rulers once lived in a tent city close to a fixed town named Kharkhorum, inhabited mainly by foreigners.

Mongolia’s vision is a “smart city” with efficient transportation, lots of open space and housing for the middle class. Around 70 percent of the city is planned to run on renewable energy, which will be challenging given Mongolia’s current reliance on coal-fired power stations. A high-speed rail line is planned to connect Ulaanbaatar and New Kharkhorum.

“The master plan for the redevelopment of the ancient city of Kharkhorum is designed to incorporate global trends and best practices in urban planning,” said Sanaa Ganbat, a spokesperson for the new city planning effort.

Planned cities have been built in various corners of the world for millennia and there are plenty of examples serving as national capitals, including Washington D.C., Brasilia, Astana, and Canberra. Indonesia is in the process of constructing a new capital, Nusantara. Shiny new cities are being carved out of forests and deserts in China, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, and elsewhere.

New Kharkhorum’s first phase includes roads, parks, government buildings, schools, and medical facilities, said Sanaa. Plans are also being laid to plant trees and protect lakes and rivers in the Orkhon Valley.

The recent competition to create a blueprint and design for the city had two winning design teams, both from China. The government says it plans to integrate elements of the winning designs into its city blueprints.

Prime Minister Oyun-Erdene Luvsannamsrai and relevant Cabinet members are the process of drawing up a framework to guide the city-building process, including a special tax regime for the city, according to Sanaa.

Construction could start as soon as next year, but progress could take decades. A full transfer of the State Great Khural, Mongolia’s legislature, and the Presidential Office from Ulaanbaatar to Kharkhorum is not expected until 2050. That timeframe means its progress will likely need to withstand changes in political leadership.

The government hasn’t said how much it will cost to build New Kharkhorum, but if planned city building in other countries is a guide the price tag could run into the tens of billions. Indonesia’s new capital is expected to cost over $30 billion. The planned city of Songdo in South Korea cost around $40 billion while another planned city, Kangbashi in China’s Inner Mongolia, cost $161 billion.

Mongolia will try to leverage public-private partnerships and investment from both Mongolia and overseas entities to help pay for construction costs, said Sanaa.

Mining is Mongolia’s main source of foreign investment – the country is rich in copper, gold, and coal. While the post-COVID-19 economy has surged on coal sales to China, Mongolia’s overall GDP is relatively small at $17.5 billion, with per capita GDP at around $5,045.

While there are significant cost challenges, history is on Mongolia’s side. Several planned cities were built in Mongolia in Soviet times and with aid from the USSR. Even the historic Kharkhorum was a planned city of sorts. Most of it was built by its foreign inhabitants in proximity to the encampment of yurts that housed the Mongolian court.

Historian and Mongolia expert Jack Weatherford described ancient Kharkhorum as a “world capital,” home to a diverse population, representing the many peoples of the Mongol Empire.

“Muslim Mosques, Christian churches, and Buddhist temples were all allowed, even forcing rival sects to live in harmony,” said Weatherford.

While Ögödei had the first permanent structures built, it was his father, Chinggis Khaan, who ordered the Mongol capital to be situated in the Orkhon Valley. This was no accident; previous steppe empires based themselves in the area for centuries, Weatherford said. Huns, Turks, and Uyghurs all used the area as a political center.

The stone monuments, gravesites, and ruined cities that these ancient people left in the area, and its continued use by nomadic people, prompted UNESCO to declare the valley a “cultural landscape.”

The most vivid account of the city was left by the Flemish Franciscan missionary and explorer William of Rubruck, who visited Kharkhorum in 1254, comparing its size to the village of St. Denis outside of Paris. The cosmopolitan city was walled and had four gates where traders sold their wares, as well as distinct quarters for its inhabitants and multiple places of worship.

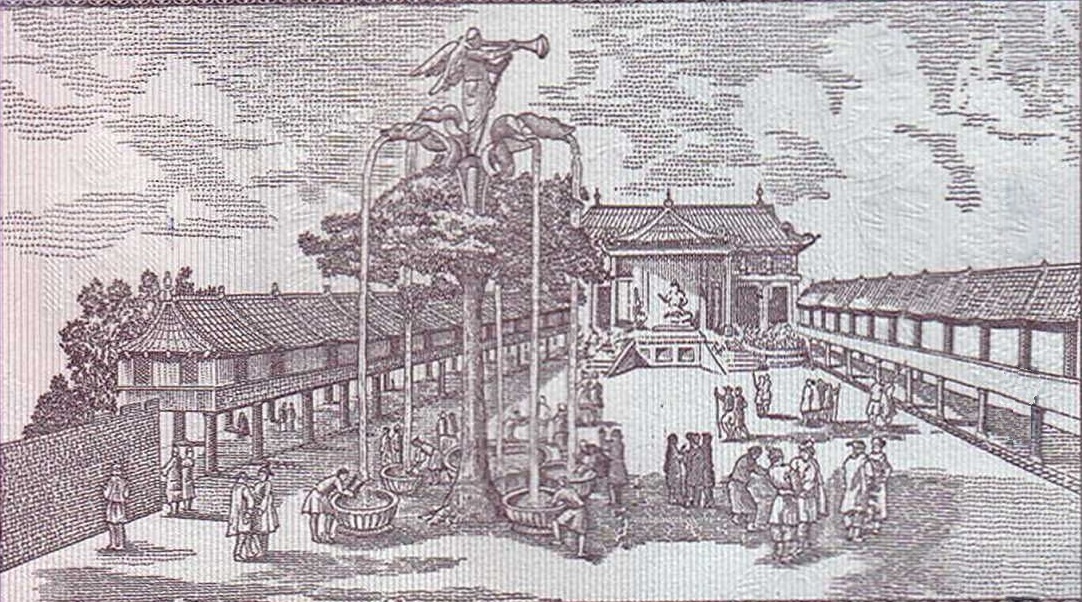

William described a great palace where the khaan would feast. A central feature was a remarkable silver fountain, shaped like a tree, from which poured four types of beverages into large silver bowls. Today the famed tree-fountain, designed by a Parisian goldsmith, features on the back of some Mongolian banknotes.

The Silver Tree at the court of Karakorum, after William of Rubruck, a mechanical aïrag fountain tree built by Parisian silversmith Guillaume Boucher. (Bank of Mongolia)

Kharkhorum remained the capital for Ögödei’s successors Guyuk and Mongke. Khublai Khaan, a grandson of Chinggis, had other ideas. He moved the capital south, eventually establishing his seat of power in Khanbaliq, the settlement that became Beijing.

After the capital moved, Kharkhorum’s fortunes waxed and waned for a century amid periods of war and peace. The collapse of the Yuan Dynasty in 1368 left it vulnerable and vengeful Ming forces left most of the city in ruins. Then, in the late 1500s, bricks from destroyed buildings were used to construct the walls of Erdene Zuu Monastery, which still stands today.

Because its ruins were collected and reassembled in a new location, there is little to see above ground for the modern-day visitor, although recent archaeological surveys show there is still much to discover underground.

Sanaa said the government has plans to increase archaeological excavations of the old capital, a project that could help Mongolia connect the old and new Kharkhorum.

But she admitted that challenges abound – not just to dig up the past and construct a new city but also to convince Mongolia’s 3.5 million current inhabitants that this monumental task is worth the cost and effort.

Critics of the project, vocal in Mongolia’s mainstream outlets and social media, point out that Mongolian politicians have floated the idea of building a new city in the past with little to show for it. Former President Elbegdorj Tsakhia started touting the capital move in the late 2000s.

“One of the biggest challenges is the weakened public confidence, as no new city has been built in Mongolia in the past 34 years,” said Sanaa. “Public skepticism is a major issue. Increasing public participation and support is key to making this project successful.”

Oyungerel Tsedevdamba is one of those skeptics. A former minister of culture in the Mongolian government, she warned that any level of urban development in the Orkhon Valley could damage or bury historic ruins.

“Any developer must carefully look into archaeology reports before putting their money into the Kharkhorum ambitions of the president,” Oyungerel said. “The real Kharkhorum is under the surface of the steppe.”

A joint German-Mongolian archaeological team recently used advanced tools, including magnetic equipment, to make a map of the city without excavations. The results show where walls and buildings once stood.

“There is so much more to study,” said Oyungerel.

The possibility of new development being built over archaeological remains is real as Mongolia ponders how to develop Kharkhorum, but the challenge is not impossible. Careful digging has allowed for development in other historic cities, including Jerusalem, Rome, and Athens.

The bigger challenge with Kharkhorum is the financial burden that construction will be on Mongolia’s already strained budget. Resources to fix Ulaanbaatar’s infrastructure challenges can’t be turned off, so the government will need to balance priorities between the new capital and the existing one.

Political will and public demands will be another ongoing battle for the project’s backers. Khurelsukh touts the city as a solution to urban congestion and pollution but tangible benefits will be years away and could haunt current and future leaders if there are delays or cost overruns.

When the original Khakhorum developed, Ögödei Khaan could fund the city’s development with tribute from across his vast empire and there was no need to appease public sentiment. The Mongolian People’s Party doesn’t have this luxury. Skilled politics and careful financial decision-making will be needed if the dream of Khakhorum is to become a reality.