Bangladesh founder-President Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s stature in the country’s public life has been diminishing since the ouster of his daughter, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, from power in August 2024. Hasina deified him, critics argue, in order to legitimize her authoritarian and corrupt rule. That has changed in recent months, and efforts are on to rewrite Bangladesh’s Liberation War history yet again.

Bangladesh’s founding father, Rahman or Mujib as he was widely known, was killed in August 1975 along with other members of his family by rogue army men barely three and a half years after Bangladesh emerged as an independent country following a bloody liberation war with Pakistan in 1971.

While Mujib did indeed play a key role in the Liberation War, the Awami League (AL) has long faced criticism for distorting history. Hasina has been accused of forcing on the people of Bangladesh a Mujib-centric history of the Liberation War, removing all other forces and personalities from the narrative or relegating them to the fringes.

In the months since Hasina’s ouster from power, Mujib’s statues have been pulled down, murals defaced, photos removed from government offices, his references dropped from textbooks, and days commemorating his life and death have been removed from the list of national days, in what is seen as a reaction to Hasina’s excesses in deifying Mujib.

However, the rewriting of history may not stop at Mujib’s role but could soon reach the Liberation War itself.

The AL and its allies allege that the forces that threw Hasina out of power are now out to erase the history of the Liberation War. It is not alone in making these charges.

“I have noticed a tendency to relegate 1971 to the background. I think this is part of the conspiracy that wants to push the people away from the real history. This is a distortion of history of another kind,” said Mirza Fakhrul Alamgir, the secretary-general of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), at an event in Dhaka on December 13. The BNP is one of Bangladesh’s two major parties besides the AL. It, too, claims the legacy of the Liberation War.

Incidentally, in recent years, Alamgir has repeatedly accused Hasina’s AL government of distorting the history of the Liberation War by turning it into a Mujib-centric episode.

As for the Jamaat-e-Islami (JeI), Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, which has long been accused of collaborating with the Pakistan Army during the Bangladesh genocide, it has sought to justify its opposition to the Liberation War, claiming that taking India’s support to win freedom was wrong.

Voices supporting the JeI’s stand are growing louder.

“I would tell people who want Jamaat to apologize for its role in ‘71 that it is the freedom fighters who should apologize to Jamaat. Because we now understand what Jamaat understood 53 years ago,” YouTuber Elias Hossain, who has 480,000 followers on Facebook, wrote on December 17.

December 16 is the day when the Pakistan Army, in 1971, surrendered to India, marking the liberation of Bangladesh. Bangladesh celebrates it as “victory day.” However, Hossain pointed out that India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi portrayed it as India’s victory over Pakistan and did not congratulate Bangladesh on the occasion. “Modi’s post yesterday proves why Jamaat did not want independence. We needed independence but not like ‘71. We will be independent the day Bangladesh becomes free from India,” he said.

According to a Dhaka University professor, who spoke to The Diplomat on condition of anonymity, JeI is “lobbying” with the current Muhammad Yunus-led interim government to ensure textbooks do not “demonize” them while mentioning the Liberation War.

The JeI is reported to exert some influence on the interim government

A Complex History

The Liberation War was fought in Mujib’s name but he himself was absent during the entire period. Arrested on the night of March 25, 1971, Mujib was lodged in a Pakistani jail until after Bangladesh attained freedom. While the AL was the main force behind the Liberation War, students, including Left-leaning ones within AL and those belonging to the Communist Party’s Chhatra Union, played a key role in creating the grounds for the liberation struggle from 1969 and during the Liberation War in 1971.

In Mujib’s absence, AL leaders like Tajuddin Ahmed and Syed Nazrul Islam played leading roles. The Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani-led National Awami Party, the Siraj Sikdar-led Purbo Banglar Sharbohara (proletarian) Party, and the Moni Singh-led Communist Party of Eastern Bengal played important roles as well.

Soon after Mujib’s arrest, a large section of East Pakistan’s Bengali army officers revolted against the West Pakistani command and joined the Liberation War. Ziaur Rahman, a major in the army, was one of them. In three separate statements issued on March 27, 28 and 29, Zia declared Bangladesh’s independence on the Swadhin Bangla Betar Kendra (Independent Bangla Radio Station). He went on to lead the Z battalion during the Liberation War and is considered among the country’s war heroes.

About two years after Mujib’s murder, Zia, then the chief of the Bangladesh army, took over as the president, emerging as the country’s first military ruler. He launched the BNP in 1978 and was killed in another military coup in 1981.

By the time Bangladesh saw its first largely-free and fair election in the country in 1991 after 15 years of military rule, school textbooks hardly had any proper history of the Liberation War. After Hasina’s AL came to power in 1996, a civil society movement under the banner of Ekattorer Ghatak Dalal Nirmul Committee that had been set up in 1992, pushed the government to start “correcting” narratives of the Liberation War in school textbooks.

However, such “corrections” were undone during the BNP-JeI rule in 2001-06, a 2009 book, Pathyapustake Muktijuddher Itihas Bikriti (Distortion of Liberation War’s History in Textbooks) by Mumtazuddin Patwari pointed out. Mujib and AL were erased and a Zia-centric history was reintroduced. After returning to power in 2008, Hasina’s government resumed its efforts to rewrite history.

During the celebration of Mujib’s birth centenary in 2020, the Hasina government erected hundreds of statues of Mujib across the country. School students took oaths in Mujib’s name and programs celebrating his life became part of the nation’s daily life. This phase saw the ‘complete Mujibization’ of Bangladesh’s history.

That is now being reversed.

Recent Trends

When Mahfuz Alam, a student leader serving as the special assistant to Chief Advisor Muhammad Yunus, updated his cover photo on Facebook in October, it triggered curiosity and controversy. All five leaders portrayed in the image were of the Pakistan movement of the 1940s who were associated with the 1947 Partition of India and the formation of Pakistan.

Of them, only Abdul Hamid Bhasani was part of the 1971 liberation struggle; the rest had either died or were inactive. Of course, Mujib’s absence, and minimal presence of the Liberation War leadership, drew people’s attention.

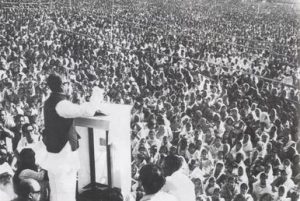

The same month, the Yunus government canceled eight national days. Six of these days involved Hasina’s family members – March 7 (for Mujib’s historic 1971 speech), March 17 (Mujib’s birthday, observed as children’s day), August 5 (Hasina’s brother Sheikh Kamal’s birthday), August 8 (Hasina’s mother Begum Fazilatunnessa’s birthday), August 15 (the day Mujib was killed, observed as national mourning day) and October 18 (Hasina’s brother Sheikh Russel’s birthday).

The two other national days canceled were November 4 (National Constitution Day, commemorating the adoption of the constitution in 1972) and December 12 (Smart Bangladesh Day).

While many supported the cancellation of national days associated with Hasina’s family members’ birthdays, the cancellation of national days on March 7 (when Mujib called the ongoing movement “the struggle for freedom”) and National Constitution Day on November 4 has evoked controversy.

Prominent civil society members have argued that these days marked events that belonged not to Mujib or his AL but to the nation. However, others point out that students in Dhaka had declared independence even before Mujib’s March 7 speech and that Mujib’s speech was a mere culmination of the students’ efforts since March 1.

So why is November 4 controversial?

When asked if a new constitution would replace the fundamental principles of “nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism” that guide the current constitution, political scientist Ali Riaz, who heads the Constitution Reforms Commission, said in a recent interview that the Declaration of Independence of 1971 had mentioned “three very key features” – equality, social justice and human dignity – that should have been Bangladesh’s guiding lights.

“These were mentioned in the Declaration of Independence but nobody remembers that because a year later, these were replaced by nationalism, socialism, democracy and secularism. I think, equality, social justice and human dignity should be our fundamental principles,” Riaz said.

From that perspective, this change does not negate or erase the Liberation War but removes Mujib from the scene. The Declaration of Independence was a work of the student leadership.

So, what will the rewriting of Bangladesh’s history entail? According to student leader Nahid Islam, who is part of the current government, Mujib’s legacy will not be erased but he will be part of Bangladesh’s history from an objective perspective.

According to a Dhaka University professor who is aware of some of the changes expected in the textbooks, stories of Mujib would be cut short, Zia’s role would be reintroduced sans the BNP-type deification, and roles of other important figures like Bhasani, Tajuddin Ahmed and Muhammad Ataul Gani Osmani (the Commander-in-Chief of Bangladesh Forces during the liberation war) would get due prominence.

In a recent article, Sohul Ahmed, a Dhaka-based researcher and writer on genocide, wrote that during her 15-year rule, Hasina leveraged legal mechanisms and selective archival disclosure to entrench her party’s version of events.

“Through these efforts, a more centralised, simplified history of the Liberation War has been constructed—one that champions the AL while marginalising the diverse voices that contributed to Bangladesh’s hard-won independence,” Ahmed wrote, adding that such portrayal “diminishes the democratic aspirations of the Bengali people and the collective nature of their struggle.”

He highlighted how courts intervened to control the portrayal of the liberation war even in fiction and memoirs. Besides, the Digital Security Act made it almost impossible for anyone to criticize Mujib or challenge the official narrative of the Liberation War, as they became punishable offenses. “National history has been reshaped into a story centered on the family’s triumphs and tragedies,” he wrote.

Ahmed told The Diplomat that the new history rewriting initiatives would not erase the Liberation War but would rescue it from the clutches of a family and a party and would restore the collective history, giving due importance to the other key figures. “No one, no political school or camp in Bangladesh opposes or rejects the Liberation War. This includes the student leadership that overthrew Hasina. Only JeI keeps trying to justify their past leaders’ actions but their arguments have few takers,” he said.

Rulers throughout the world – especially those of the authoritarian kind – have tended to weaponize history for political dominance. How Bangladesh’s present struggle over history is fought and resolved will surely impact the country’s future.