Shortly before midnight on December 2, 1984, a terrible cloud, consisting of tons of the deadly gas methyl isocyanate (MIC), along with other chemicals, began to leak into the atmosphere from the storage tank of the U.S. multinational corporation Union Carbide Corporation (UCC)’s pesticide plant on the outskirts of Bhopal in central India.

The immediate consequences of the mass poisoning were catastrophic. As many as 10,000 people are believed to have died within three days of the leak.

As the world marks the 40th anniversary of the disaster, what lessons should we take from what happened on that awful night? I think perhaps there are at least three important ones. First, and perhaps most obviously, is that a single tragic event can have consequences that last generations.

As well as those who succumbed to the gas in the first few hours, many thousands more people were exposed to it, and they continue to suffer from a range of chronic and debilitating illnesses. It is now estimated that more than 22,000 people have died as a direct result of exposure to the leak, while more than half a million people continue to suffer some degree of permanent injury.

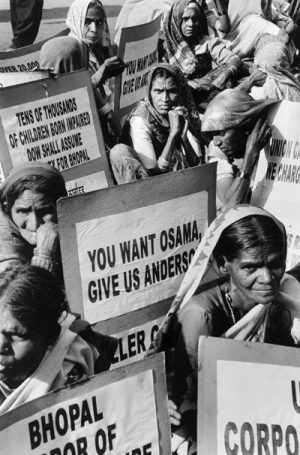

Shockingly, it is not only people exposed to the gas directly who have been affected. Over the years that followed, a large number of children born to gas-exposed parents have been affected by growth retardation, birth defects, and other medical conditions.

Meanwhile, to this day, thousands of tons of toxic waste remain buried in and around the abandoned plant. This has contaminated residents’ water supplies and harmed their health, adding to the already dismal health status of gas-exposed residents.

As well as the health impacts, the tragedy has pushed already impoverished communities into further destitution. In many families, the main wage earner died or became too ill to work. Women and children suffered disproportionately.

An unfortunate second lesson of the Bhopal tragedy is how easy it has been for UCC to escape accountability. Pitted against the largely poor victims of the gas disaster was the hugely powerful and enormously rich multinational corporation, which escaped being forced to provide the survivors, their children, and grandchildren with adequate compensation and medical care.

The catastrophic gas leak was the foreseeable result of innumerable operational failures at the plant, but from the start, UCC’s response to the disaster was inadequate and callous. For example, although thousands of people were dying from gas exposure, or suffering agonizing injuries, UCC withheld critical information regarding MIC’s toxicological properties, undermining the effectiveness of the medical response. To this day, UCC has failed to name any of the chemicals and reaction products that leaked along with MIC on that fateful night.

In 1989, without consulting Bhopal survivors, the Indian government and UCC reached an out-of-court compensation settlement for $470 million. This amount was less than 15 percent of the initial amount sought by the government, and far less than most estimates of the damage at the time. Thousands of claims were not registered at all, including those of gas-exposed children under the age of 18, and children born to gas-affected parents who, time later showed, were also severely affected.

There have been numerous attempts to hold UCC and individuals to account, either through criminal or civil claim proceedings launched in India and the U.S. But these have had no or very limited results.

One challenge has been created by the restructuring of the business entities involved in the tragedy. UCC sold off the India-registered subsidiary that operated the plant. It was then, in turn, bought by another giant U.S. corporation, the Dow Chemical Company. To this day, Dow shamefully claims it bears no responsibility since it “never owned or operated the plant” and that UCC only became a subsidiary of Dow 16 years after the accident.

In 2010, the Chief Judicial Magistrate’s Court in Bhopal found seven Indian nationals, as well as UCC’s India-based subsidiary, guilty of causing death by negligence. By contrast, U.S. individuals and companies have escaped punishment, and there is significant evidence that the U.S. authorities have helped protect them.

Companies have a responsibility to respect human rights wherever they operate. Dow may not have caused the gas leak, but it became directly linked to the tragedy after it bought UCC. The company boasts of following the highest human rights standards, but its continued failure to respond to the urgent needs of the survivors is utterly disgraceful.

But there is a third lesson to be drawn from the tragedy and its aftermath. It can be found in the inspiring story of the survivor groups and their supporters, who over 40 years have refused to give up their fight for justice. They have initiated or intervened in many legal actions; conducted scientific research into the contamination and health impacts; and they have launched practical initiatives in the absence of sufficient state and corporate support. For example, in 1994, survivor groups raised funds for the Sambhavna Trust Clinic and they later opened the Chingari Rehabilitation Centre. Thousands of gas- and contamination-affected adults and children have benefited from the highly specialized and professional medical care and rehabilitation provided by these institutions – unparalleled by any of the government-run facilities.

Their campaigning has also meant that Dow has never been able to disassociate itself from the Bhopal disaster. Until it finally addresses the needs of the survivors, their campaign will continue.