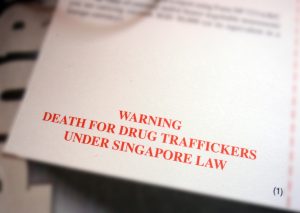

If the Singaporean police’s website is anything to go by, there was one murder in the city-state in November – or, at least, one person was arrested for murder last month. The annual and semi-annual reports on crime briefings found on the police website do not provide data on homicides, preferring to focus on voyeurism and “outrage of modesty.” Yet we do know that there were at least four other murders last month: those committed by the state. Four people were executed last month, making it nine individuals for the year and 25 since Singapore ended a COVID-19-imposed moratorium on the death penalty in March 2022.

The very same month that the Singaporean state took four people’s lives, its government joined only 20 other countries in voting against a resolution on the moratorium on the use of the death penalty at the U.N. General Assembly. Some 131 U.N. member states voted in favor; even the other Southeast Asian countries that still persist with capital punishment, including Thailand and Vietnam, abstained. It says something when even the theocratic thugs in Tehran appeal for Singapore to show some “humanitarian consideration,” a response to a Singaporean-Iranian being killed by the city-state last month.

I have used this column to condemn the death penalty since I began it in 2016. I don’t intend to stop, although the interested reader would do well to listen more closely to the likes of Kirsten Han, a journalist far more eloquent on these matters. A usual response one hears from apologists and stalwarts of capital punishment is that it’s a question of sovereignty – that every nation has the right to decide which universal natural right they will violate. “Yes, yes, human rights are universal in nature but not in application,” the purveyors of “Asian values” still say. Singapore even attempted to include the sovereignty clause as an amendment to the U.N. General Assembly resolution last year, much to the annoyance of the likes of the European Union.

Alternatively, those who want to keep the hangman in employment will retort: “Well, the United States has the death penalty, too, so why should we stop?” Indeed it is one surviving remnant of 18th-century barbarism that hasn’t been repealed in America – or, at least, not repealed by 13 states which still can and do execute people. But the whataboutery ends as soon as one suggests a negative comparison: the United States also has First Amendment protections on free speech, yet Singapore has amongst the world’s most restrictive laws on speech, so why not aspire to American standards in this regard, too?

The other mea culpa is that capital punishment isn’t cruel or unusual since almost every country has laws permitting someone to murder another person lawfully, so why not extend this to the state? In most countries, indeed, you wouldn’t be imprisoned, let alone hanged, for murder in self-defense – and for Singapore, the destruction of a drug trafficker is deemed necessary for the defense of the rest of the citizenry. (For the rest of the citizenry, incidentally, who can get on a flight to Bangkok or Phnom Penh and snort, smoke, and inject as they please, as many do.)

Yet, in almost all cases of murder for self-defense, one finds a timeline of events rather distinct to capital punishment: Someone is threatened; they kill the source of the apparent threat; and then a court or tribunal determines whether laws on self-defense can justify their act. The distinction of the death penalty is that the murder takes place only after the suspect no longer poses a threat; after he or she has been dispossessed of the narcotics that apparently are a danger to the national health.

Just consider how odd it would be if a different timeline was followed, albeit one that served the exact same ends. If every drug trafficker was shot dead by the Singaporean police as they were picking up their narcotics-stocked suitcase off the baggage carousel in Changi Airport, most people would consider this an unusual and, dare I say, unlawful or bestial way to go about things. Why not just arrest them? Why shoot first? But is this really the stranger of the two chronologies? The Philippine policeman who shoots dead a suspected drug dealer has no way of knowing what future crime that person might have committed had they not been butchered in cold blood. Yet the Singaporean judge who passes the death sentence knows that, first, the defendant has not injured anyone (since the narcotics they were carrying were confiscated) and, second, knows that the defendant will no longer pose a threat since the same judge could sentence them to decades in prison.

Moreover, almost every country in which murder for self-defense is legal would consider it illegal if you apprehended an intruder, removed them of what weapon they might have used to injure you, tied a rope around their neck, and then hanged them – and only later professed that this was an effective deterrent to other potential intruders who may break into your home in the future.

What one finds is that the hangman doesn’t mete out justice. His job is purely to act as a deterrent. And, indeed, a deterrent against unknown and potentially non-existent future criminals. I do not believe the Singaporean government has ever committed to stop murdering drug traffickers if the amount of drug-related crimes falls below a certain threshold. In other words, if the apparent deterrent factor is no longer required.

Of the nine executions carried out in Singapore this year, eight were for drug trafficking and one for murder. I assume that there hasn’t been only a solitary murder this year (indeed, the state has carried out nine by itself), so the discrepancy between the two crimes is baffling. The murderer who’s hanged has already taken another person’s life; the drug trafficker has personally injured no one since the consequence of their crime was prevented. Nonetheless, their death serves pour encourager les autres. In 1764, the Italian philosopher Cesare Beccaria described capital punishment as a “war of the whole nation against a citizen whose destruction they consider necessary.”

This deterrence defense is, however, rather convenient since it’s neither provable nor disprovable. How much safer does murdering drug traffickers make Singapore? 10 percent? 50 percent? 80 percent? Speaking on this subject in May, Home Minister K Shanmugam proclaimed that his was an “evidence-based” ministry and “evidence shows clearly that the death penalty has been an effective deterrent.” Now, good, some evidence.

“In 1990,” he explained, “we introduced the death penalty for trafficking more than 1.2kg of opium. In the four years that followed, there was a 66% reduction in the average net weight of opium trafficked.” Okay. And his ministry conducted a survey in 2021 of people from drug-producing areas of the world and found that 87 percent “believed that the death penalty deters people from trafficking substantial amounts of drugs into Singapore” and 83 percent “believed that the death penalty is more effective than life imprisonment in deterring drug trafficking.”

So the evidence is a three-decade old crime statistic and a public opinion survey of (presumably) people not in the drug-mule business and carried out by people who wanted to prove deterrence works? It’s quite one thing for someone to tell a pollster they wouldn’t smuggle drugs in fear of capital punishment and quite another when a cartel promises you a lifetime’s fortune for doing so. Moreover, earlier in his speech, Shanmugam noted that the number of drug abusers arrested in 2023 increased by 10 percent from the previous year, while the number of cannabis abusers reached a 10-year high last year. So evidence that deterrence works is that drug use (so presumably also the supply of drugs) is increasing?

To get an actual “evidence-based” answer, one would have to radically alter almost every aspect of the city-state. Possibly, what actually makes Singapore so safe is having one of the highest GDPs per capita in the world, having low unemployment, having good social protection, having a tradition of stable families, having very restrictive immigration laws, and having incredibly repressive laws against any unsocial behavior (that don’t end up with being hanged if you break them). If, for a year, the government was to impoverish the masses, strip away the powers of its police to interfere in the daily lives of the citizenry, and fling open its borders, yet all the while continuing to executing drug traffickers – only then could one gauge with any certainty whether there’s any causality between the hangman’s noose and being able to walk around at streets at night unmolested by junkies.

As such, one could argue that capital punishment has zero impact on the nation’s safety and possess as much evidence as the government does to argue the reverse. What one is left with, then, is simply a dispute between opinions and ideals, one occasion when the Singaporean government forgets its founding principle of pragmatism. (Or, rather, the founding myth of reason.) More specifically, it’s a dispute between a government that can repeat an opinion and a citizenry that’s expected to swallow the wisdom of authority.

When France did away with the peine de mort in the early 1980s, Francois Mitterrand’s Minister of Justice said the scaffold had come to symbolize “a totalitarian concept of the relationship between the citizen and the state.” Totalitarian, indeed, in the act itself and in a state’s ability to dictate to the rest of society why they should also think it necessary to destroy another person’s life. After all, the state is murdering people on behalf of the average Singaporean.