The ongoing freeze on U.S. foreign aid is impacting the globe, but its ramifications are different in each specific location. In Afghanistan, the United States is not merely withholding assistance; it is deepening a humanitarian catastrophe and punishing civilians for political decisions beyond their control. If history has taught us anything, it is this: abandoning Afghanistan does not foster stability – it entrenches suffering and fuels crises that inevitably spill beyond its borders.

The Taliban, insulated by mineral wealth, taxation, and regional trade, will endure. It is ordinary Afghans – the hungry, the sick, the desperate – who bear the full weight of these decisions. They are the ones selling their last possessions, rationing their final scraps of food, and watching their children waste away while the world debates policies from a comfortable distance.

Afghanistan’s tragedy is not new; it is a cycle the world refuses to break.

Each time I stand before the shelves of a bakery, the scent of fresh loaves, the dusting of flour, and the quiet patience of those waiting in line transport me back to Kabul – to the bitter years of the first Taliban regime (1996-2001). Back then, hunger was not just a fear but a certainty.

I grew up in the East Kabul neighborhood of Microryan, a Soviet-built area bearing the scars of a brutal civil war: bullet holes on the walls, crumbled cement staircases, and graves oddly placed on street corners in front of houses. Every day, I stood outside the neighborhood bakery waiting for the five loaves of bread we received for free.

The Taliban rule marked the cruel end of a civil war, a long and tragic chapter for Afghanistan. However, the Taliban’s takeover also plunged Afghanistan into deeper isolation, a move that left the country dependent on limited international aid, with few countries – Pakistan, the UAE, and Saudi Arabia – recognizing the regime. The ensuing years were defined by economic collapse, hunger, and suffering for ordinary Afghans.

My family, like many others, relied on the meager rations provided by aid organizations, a lifeline in a time of desperate need. Great relief came to us when an aid organization gave us a card, granting us five loaves of bread each day from a designated bakery, an exhausting walk from our home.

Every day, long lines formed in front of the bakery: men, women, and children, all desperate for their share. Women draped in mustard-yellow and greenish burqas resembled autumn trees, shivering and vulnerable, extending their thin hands like dried branches reaching for bread. Children’s eyes, wide and hollow, bulged from hunger and the scars of unending conflict. The men, in tattered clothes with unkempt beards and wild hair, resembled ghosts from a forgotten war.

For the timid, shy girl I once was, the crush of bodies around me deepened my terror. Yet, in that line, I stood resolute. Even when men pinched, shoved, or pressed too close, nothing could break my resolve. Call it abuse – nothing could stand between us and survival.

I used to clutch the five loaves of bread so tightly to my chest, careful not to lose a single piece on the way home. The heat pressed against my heart – a comfort in the bitter winters of Kabul, though it scorched my arms in the summer.

The bread was heavy, thick, and coarse. It came from the United Nations’ World Food Program (WFP). Some speculated that the U.N. mixed flour with cheap fillers to stretch the supply. Others believed bakers added low-cost additives to make the loaves denser.

But we didn’t care; after all, it was food. And it was free. That was all that mattered to us. Without it, my family, along with thousands of others, might not have survived. We, the civilian population, suffered the consequences of decisions we had no control over, punished for choices made without regard to our cries for help.

Fast forward to today, and the situation in Afghanistan bears an eerie resemblance to that bleak past. Afghanistan once again finds itself isolated, with sanctions and aid restrictions punishing the same vulnerable population.

The crisis unfolding today is not just a repetition of history – it is an amplified version, with even fewer lifelines. Millions of Afghans, particularly women and children, face escalating hunger and health crises. The United States, once a critical player in the country’s fate, has withdrawn its support, leaving the Afghan people to fend for themselves once again.

The United Nations reports that over 28 million Afghans, or two-thirds of the population, require urgent humanitarian assistance. More than 6 million are on the brink of famine, and children are dying daily from malnutrition.

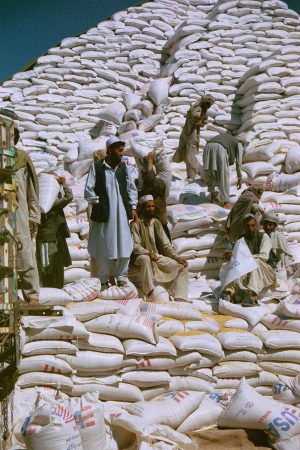

With no country recognizing the Taliban regime and heavy restrictions, the United States remained Afghanistan’s largest donor, allocating nearly $21 billion in aid since the military withdrawal in 2021, primarily channeled through USAID. This aid meant that ordinary civilians – desperate Afghans like my childhood self – could still receive the most urgently needed support for survival. In 2024, USAID alone committed $280 million to the World Food Program to address Afghanistan’s worsening food crisis.

The recent suspension of USAID funding has resulted in the cessation of critical health services, including the provision of HIV and malaria prevention medications, thereby exacerbating the humanitarian crisis and leading to immediate and severe public health repercussions.

While I acknowledge Secretary of State Marco Rubio’s argument that “foreign aid is not charity,” the United States prides itself on defending human rights. The U.S. often positions itself as a champion of standing with its allies and friends, a global leader in promoting democratic values, human rights, and stability. Yet, it would be unjust and ethically troubling to overlook the fact that Afghans were crucial allies during the Cold War and the War on Terror – contributions paid with the blood of millions of young Afghan men and women.

While the United States and its Western allies supported Afghans’ fight against the Soviet occupation (1979–1989), once the Soviets withdrew, Afghanistan was left to navigate the ruins of war alone. As the West celebrated the fall of communism, Afghans – we who had broken the back of the Red Army – were left to grapple with its haunting aftermath: a nation scarred by amputees, millions of landmines, and mass graves. The mujahideen – once hailed as holy worriers – had grown all too accustomed to killing, seizing territory, and wielding unchecked power. They morphed into ruthless warlords, turning their guns on civilians. The world merely watched.

Despite immense suffering, the Afghan public once again stood by the U.S.-led Global War on Terror and paid with their blood. Between 2001 and 2021, an estimated 66,000 to 69,000 Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) personnel lost their lives in the war in Afghanistan.

According to the last Afghan president, Ashraf Ghani, over 45,000 members of the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) lost their lives between 2014, when he assumed leadership, and the end of 2019.

Hundreds of thousands of Afghans stood against the Taliban, fellow Afghans, aligning with U.S. forces, and, by extension, endorsing the invasion. They did so not out of blind allegiance but out of a fragile hope: the belief that the United States’ intervention signified a genuine commitment to rebuilding Afghanistan from the wreckage of the Cold War, which had already left their lives in ruins.

Yet, if the abrupt U.S. withdrawal was a betrayal, what followed was even more devastating. For many, it felt less like a strategic recalibration and more like a ruthless disavowal – a severing of ties so complete it was akin to a final, gut-wrenching blow.

This time, too, it is the innocent who will bear the cost. With millions already on the precipice of starvation and battling outbreaks of malaria and HIV, severing aid – a crucial lifeline – would only accelerate the country’s collapse.

As things stand, the consequences of the U.S. abandonment of Afghanistan are not just humanitarian – they are geopolitical. History has demonstrated that turning away from Afghanistan invites disaster. The vacuum left behind does not merely imperil ordinary Afghans; it creates ideal conditions for extremist groups to exploit desperation, perpetuating the very cycle of poverty and radicalization that the United States spent decades attempting to dismantle.

Beyond Afghanistan, America’s retreat carries significant geopolitical consequences, reshaping regional power dynamics and emboldening its adversaries.

While some critics argue that foreign aid strengthens the Taliban’s hold on power, many others view this perspective as misguided. Aid isn’t handed to the Taliban. It’s distributed by independent organizations like the World Food Program and UNICEF, reaching the most vulnerable, particularly women and children, under strict monitoring systems.

And even if a fraction were to end up with the Taliban, is it acceptable to let women and children starve for the actions of those in power?

No. Having lived through the devastation, suffering, and hopelessness, I can attest that it is only the innocent who bear the cost. Does punishing the innocent for the choices of the few truly serve anyone’s purpose?

Moreover, the Taliban have expressed their willingness to mend ties with the United States.

Amir Khan Muttaqi, the foreign minister of the Taliban’s de facto government, referenced the 2020 Doha Agreement in a BBC interview in January, emphasizing that both sides had explicitly agreed upon a cessation of hostilities. “If the U.S. wants political and economic engagement with Afghanistan, we do not have a problem,” Muttawi said.

He also said that the road to the U.S. embassy in Kabul is now open to the public and might be reconstructed. “Any ambassador or representative is welcome to cross the path,” he added.

This might seem like an invitation for the U.S. to re-establish its political presence in the country. While the door to diplomacy may be open, at least from the Taliban’s side, it does nothing to change the harsh reality faced by millions of Afghans.

The United States must urgently reinstate aid to Afghanistan, ensuring it reaches those most in need – particularly women, children, and marginalized communities. This is not merely strategic; it is a moral imperative. To delay or deny assistance is not just an oversight; it is an abdication of moral responsibility.

As an American, I believe that standing by while Afghans endure unimaginable suffering challenges the very principles this nation stands for. Turning away is a choice. So is standing up. The U.S. must decide what legacy it wants to leave behind. In the end, history will judge America, not by its wars won or lost, but by the people it chose to support – or abandon.

Twice, the United States has witnessed Afghanistan fall. Can the U.S. afford to turn away again?