The study of great powers and great power rivalry has recently gained increased prominence particularly because the world today seems to be moving away from being dominated by a single power or characterized by the dominance of institutions. While the 19th-century balance of European powers is most often cited as a prior example of a period characterized by great power rivalry, it is not the only such period. Indeed, throughout much of Asia’s history, great powers have competed against each other.

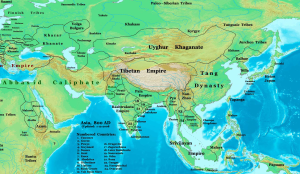

This is the first of a series of articles that will cover the medieval and early modern great powers of each of Asia’s regions: East Asia, Central and North Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and West Asia (the Middle East). Each article will cover the great power dynamics of the main powers within that particular region as well as how the main powers of each region interacted with those of other regions. For example, the Tang Empire of China, East Asia’s dominant power for three centuries, competed against many local and distant powers such as the Uyghur Khanate, the Tibetan Empire, Goguryeo in Korea, and even the Abbasid Caliphate based in the Middle East.

By the medieval era, the people of what we know today as Asia perceived that their landmass was filled with several great powers. For example, the 9th century Arab text, the Silsilat al-Tawarikh, declares that “both the Indians and Chinese agree, that there are four great or principal Kings in the World; they allow the King of the Arabs to be the first…The Emperor of China reckons himself next after the King of the Arabs, and after him the King of the Greeks [Byzantium], and the Balhara [Vallabha-rāja of the Rashtrakuta Empire]…this Balhara is the most illustrious Prince in all the Indies….”

Slightly later, Abu Zayd al-Sirafi’s 10th century Akhbar al-Sin wal-Hind (Accounts of China and India), relating the visit of Ibn Wahab to the court of the Tang Emperor at Chang’an (Xi’an), reported that:

…the king [of China] said to his interpreter, ‘Tell him that we count five kings as great. The one with the most extensive realm is he who rules Iraq, for he is at the center of the world, and the other kings are ranged around him; we know him by the name ‘the King of Kings.’ Next comes this king of ours, whom we know by the name ‘the King of His People’, for no other king is more astute a ruler than we nor more in control of his realm than we are of ours, and no other populace is more obedient to its kings than ours; we are therefore the Kings of Our People. After us comes ‘the King of Beasts,’ who is our neighbor the king of the Turks, and after the Turks comes the King of Elephants, that is, the king of India, whom we know as ‘the King of Wisdom,’ because wisdom originates with the Indians. Finally comes the king of Byzantium whom we know as the ‘King of Men,’ for there are no other men on Earth who are more perfect in form than his men, nor any of more handsome countenance. These five are the foremost kings. All the rest are beneath them in rank.

Putting aside the unlikeliness that a Chinese emperor would acknowledge any other ruler as equal to — let alone greater than himself — what emerges is a sense that civilizations as disparate as the Chinese and the Arabs understood that there were a certain set of great powers — “foremost kings” — in the world. These lists almost invariably include China, India, and great powers based in the Middle East, the steppes of Central Asia, and in the Mediterranean region or Europe. It paints a picture of the great powers of the medieval world that is not that different from those of today, which demonstrates the staying power of geography, demographics, and resources. These are the reasons why great powers are great powers. They have sizable populations, geopolitical locations, or economic resources that allow them to generate wealth and build and project military power beyond their borders.

With the exception of the United States, most of these other great powers have clear successors in Asia or Europe, which is really a Western promontory of Asia. China, India, Russia — as a successor to the steppe empires — the European Union, Iran, and Turkiye can all lay claim to being great powers of the modern world, as their predecessor states were. Additionally, joining their ranks are other Asian powers that may be counted among the foremost, including Japan and Indonesia. Interspersed between both the medieval and modern powers were prominent cities that functioned as wealthy entrepôts that helped lubricate trade. In the past, Samarkand, Khotan, and Malacca, to name a few, were prominent; today, we have Singapore and Dubai.

The 21st century is often characterized as a time of increased great power rivalry and a return to a multipolar world with a balance of power between nations. But most of the great powers of our time will be Asian powers, and so it must be said that the new era of great powers will be an era of Asian powers and an era of Asian geopolitical rivalry. The world changes but nothing changes.