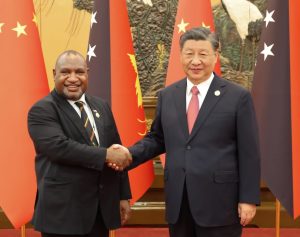

At the end of April 2024, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi made a high-profile visit to Papua New Guinea (PNG) just before a similar trip by Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese. Albanese was there to walk the hallowed World War II Kokoda Track with his PNG counterpart, James Marape, in a two-day display of bromance steeped in both history and contemporary concerns.

In a telling incident, a helicopter carrying the two prime ministers was disrupted by a large Chinese cargo plane delivering aid tied to Wang’s visit. The incident was no doubt intended to send a geopolitical message. The message was for Australia but also Papua New Guinea, particularly to Marape who plays a pivotal role in managing the increasingly complex web of geopolitical maneuvers shaping his nation. The whole Pacific is grappling with Beijing’s multifaceted campaign to become the dominant regional power and the pushback from a coalition of nations aligning against China. PNG is experiencing this competition in unique ways that have vast consequences domestically and internationally.

The geopolitical pressures and relationships shaping PNG have particular and intense forms due to the country’s size – it is the largest Pacific nation after Australia – its location at the strategic center of the Indo-Pacific region, as well as PNG’s uniquely complex domestic realities. The geopolitical game playing out in PNG is mapped onto what seems at times to be a precarious domestic situation.

While Marape cuts a self-assured political figure on the international stage, courting many nations seeking stronger ties with PNG, the events of 2024 have challenged his domestic authority. Indeed, Marape has deftly used opportunities presented by the flood of foreign interest in PNG to offset domestic criticism of his leadership. This was evident when Marape made a high-profile appearance as a guest of the Australian government (the equivalent of a state visit) in February 2024, and became the first Pacific leader to address Australia’s Parliament. This came at a particularly opportune moment for Marape given the domestic turbulence that preceded it.

Although PNG is a nation all too familiar with unrest and a plethora of social and economic challenges, the country was shaken by riots that broke out on January 10 in Port Moresby, which turned the capital into a warzone. Deep economic and social frustrations were unleashed in a blaze of lawless looting and arson. The cost was high both in human life – at least 22 died – and monetarily. The damage bill was put at 1 billion kina (around $260 million). In the immediate aftermath of the riots, Marape resisted calls to resign and instead suspended Parliament until mid-May to foil political moves intended to exact a toll on his leadership and government.

After Marape visited Canberra in February, more violence erupted – this time in the province of Enga on February 18. A tribal fight exacerbated by high-powered weapons turned ancient animosities, amplified by economic and social frustrations, and a lack of government authority into mass bloodshed. At least 50 people were ambushed and killed in this latest episode of violence in PNG’s Highlands. Like the riots in Port Moresby, this deadly ambush shone a harsh light on numerous shortcomings, not least the PNG government’s ongoing inability to provide adequate policing and security.

In late May the horrific tragedy of a landslide that is thought to have buried alive nearly 2,000 people from villages in Enga Province exposed additional serious shortcomings of Marape’s government. Enga community leader, Ruth Kissam, pointed to the failure of political leaders to respond urgently and adequately to the tragedy and save lives because they were more focused on political machinations instead.

As with the January riots and the Enga tribal ambush in February, the May landslide will echo domestically as political recriminations play out and geopolitically as reconstruction will draw international support that will further feed into the unfolding contest.