There is growing concern that China’s economy may face a slowdown because of speculative investments in local government financing vehicles and real estate. This type of crisis would mirror that which occurred in the U.S. in 2007-2008, with asset price declines in real estate leading to liquidity and solvency issues in overleveraged financial institutions, triggering a financial crisis. Although China’s financial leverage ratios are not as high as those in the U.S. preceding the crisis, and the Chinese government is often considered a backstop for the loan operations of the banking system, there is still good reason for this concern.

First, some of the shadow banking products are based on these loans to local government financing vehicles and real estate. Local government financing vehicles have been building infrastructure that has not been profitable. For example, ghost towns throughout China have been constructed without attracting residents or businesses. Some towns involve extravagant touches, mimicking New York City or Paris. Much of the borrowing carried out by local government financing vehicles, through trust loans, bond financing, or other financial mechanisms, is now recognized as being used to make payments on the existing debt. Real estate development is also increasingly risky in some places since there are recognized bubbles in several property markets, ensuring that the higher property prices rise, the harder property owners will fall on the downswing, especially if they have borrowed against the existing value of their property.

Second, the shadow banking products are interconnected in a way that is not transparent, so that financial failures in one area of the financial economy may bring down other sectors as well. For example, credit guarantee companies have guaranteed the loans of other companies, and have themselves lent to companies, often creating complex webs of interconnectedness. Failure of one company in the web has in the past threatened the entire chain of connected firms and has required government intervention. In another example, the underlying loans for non-standard debt assets of wealth management products sold by banks to individual customers are often based on trust loans, entrusted loans, or bankers’ acceptance bills, which have been extended to risky borrowers like the real estate developers mentioned above. Individual customers bear the risk if these income streams dry up, as the regulatory authorities have declared that the government will not be held responsible. Many other instances of interconnectedness exist, but the bottom line is that holders of shadow banking assets are not safe from a potential crisis.

To illustrate the mounting risk in a slightly more formal way, I use a concept that I refer to as the “speculative spread.” This spread shows the difference between components of the asset and liability side of the financial sector. Although I have phrased and applied this relationship somewhat differently to Europe and the United States, the basic idea is that if the relationship between shadow banking (speculative finance) and financial deepening (real finance) gets too far out of whack in the wrong direction, the financial economy becomes unstable.

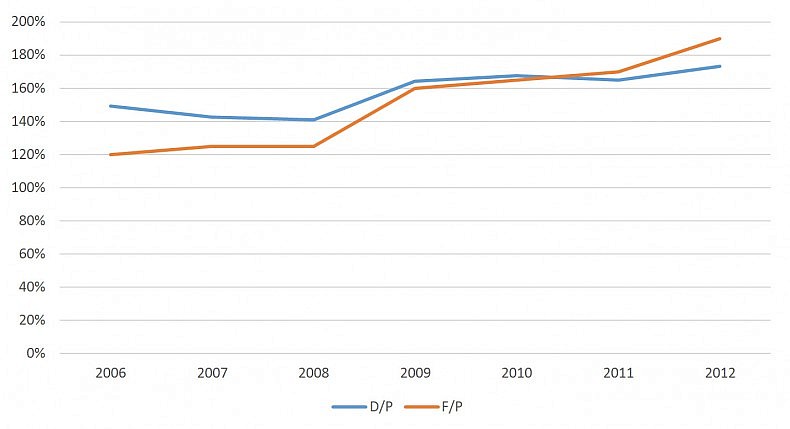

I had performed the calculations on the United States and the Eurozone during the crisis, finding that the U.S. had an unstable financial economy, while the Eurozone, for all of its debt disasters, had a relatively stable financial economy, with the exception of the period leading up to the crisis in 2007. Recently, I performed the same task for China, and found that somewhere at the end of 2010 and the beginning of 2011, the “speculative spread,” or gap between financial sector liabilities and assets (or total social financing to GDP (F/P) and M3 to GDP (D/P)) has become positive and has grown. What this says is that there is an increasing number of relatively illiquid non-traditional assets; from the analysis above, we know that their risks may be higher than normal. Although admittedly we are not comparing apples to apples (these assets do not one-for-one match liabilities), we do know that a firm that possesses liabilities greater than assets will go under. If these non-traditional assets sour and become non-performing, as bank loans are increasingly doing, they can pose a real threat to China’s financial balance sheet.

Right now, speculation is now outstripping normal finance and China is in danger of experiencing a crisis of solvency. The figure below shows financial system liabilities outstripping assets; the difference is investment in speculative activity.

China watchers believe something like this has been happening and there have been many news stories about China’s increasing indebtedness. Financial journalists have shown that a rise in quasi money (M2 minus bank loans) also follows this trend. The fact that financing (including shadow banking) is larger than the greater liquid money stock is worrisome; this means that there are potential liquidity and solvency issues buried in the financial economy. Although better developed nations may be able to bear a greater financial liability to asset ratio, China’s still relatively shallow financial system presents a cause for concern.

China financial scholars are eminently aware that something grim lies ahead and many are hopeful that reforms to be pushed through by President Xi Jinping and Premier Li Keqiang will resolve some of the negative financial outlook. However, even if the financial sector is reined in, it seems the only way to really overcome this unstable “speculative spread” is to specifically target the shadow banking sector and curb its activity. It has been noted that monetary tightening will lead to a slowdown in credit growth and GDP, but it may not have the effect of curbing the shadow banking sector compared to less risky financial activity, and could even exacerbate the speculative spread.

Therefore policy aimed directly at the shadow banking sector is a far better idea: it could eliminate the threat of financial instability at its root. Reducing the risk of loans extended by trusts, or through banks as entrusted loans, and curbing the issuance of bankers’ acceptance bills can rein in the growing speculation and help to balance China’s financial sector as it is further reformed. As the financial sector is gradually liberalized and developed, the financial sector may be able to better handle the creation of non-standard debt assets.

Right now, however, this is something that should not be overlooked and presents a real threat to the Chinese economy. As sexy as it is to study illicit financial flows—particularly for those who profit from them—China watchers are right in fearing the intangible financial instability inherent in China’s current composition of financial flows.

Sara Hsu is Assistant Professor at the State University of New York at New Paltz.