The military’s top intelligence officer said that spying on China isn’t enough in and of itself. Rather, the U.S. needs to do more to cultivate analysts with a deep understanding of Chinese strategy and goals.

Rear Admiral Paul Becker, the Director for Intelligence on the Joints Chiefs of Staff, made the remarks during the inaugural Intelligence and National Security Summit in Washington DC last week. According to Breaking Defense, Becker said that U.S. has a “data glut but an information deficit” when it comes to China. Specifically, Becker pointed to a lack of understanding regarding China’s “interim objectives” and “main campaigns.” “We need to understand their strategy better,” he said.

It’s not the first time Becker has made similar comments. Speaking at a roundtable back in February, Becker noted that intelligence gathering “involves not just the ability to collect and transfer large amounts of data regarding military, commercial, social and economic networks, but a deep understanding of a potential adversary’s’ strategies, mindsets and intent.” He cautioned that a firm grasp of strategic goals is essential for shaping policy: “If one doesn’t understand a potential adversary’s strategy, then one might think the adversary is conducting random acts. And to counter those random acts, we would ourselves conduct random responses.”

When it comes to understanding China, Becker is not impressed with the U.S. intelligence community. He questioned how many analysts really understood China, whether on a grand strategic level (“What are Chinese core interests?”) or dealing with specifics (Why is China’s nine-dash line “not solid”?). Becker’s main point is that, without this greater understanding of strategic goals and calculations, hard intelligence on capabilities is of little use. In a March interview with KMI Media Group, Becker further explained that increasing U.S. understanding of China could be the key to avoiding a conflict altogether. “One way we can avoid drifting toward conflict is through a deep understanding of China’s grand strategy, mindset, intent and the physical environment of their nation and its periphery,” Becker said.

Many of the points of tension in the U.S.-China relationship have to do with intelligence gathering, from allegations of widespread cyber espionage by the U.S. National Security Agency to arguments over the legality of close-in surveillance. Those arguments, while undoubtedly important for the future of U.S.-China relations, obscure a deeper problem — does the U.S. know how to use the intelligence it is gathering?

The issue of understanding China’s strategy extends beyond the intelligence community to U.S. foreign policy sphere in general. Inevitably, there’s something of a lag in shifting a government’s focus from one foreign policy challenge to another. Governments naturally groom experts to understand the adversary du jour; when the focus changes, it will take years for a new crop of analysts, trained with a new focus, to work their way through the ranks. We’re still seeing the tail end of Soviet experts, those who entered the foreign policy and military ranks in the 1980s, today. Following them, there’s a whole new generation of experts on Middle East issues and counterterrorism trained in the post-9/11 era. The government is only now starting to make a concerted push for more Asia-Pacific experts (and particularly, China hands) — it will take years before this new crop of advisers reaches senior positions.

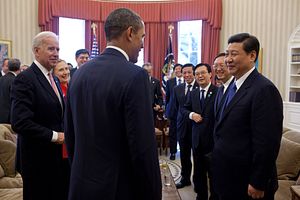

Though the Obama administration routinely describes the U.S.-China bilateral relationship as one of the most important in the world, the administration’s make-up hasn’t always reflected this. When Obama took office in 2009, two of his top Asia-Pacific advisers were indeed well-versed in China issues. Jeffrey Bader, who served as the senior director for Asian Affairs on the National Security Council, focused much of his State Department career on China. Over at the State Department, Deputy Secretary James Steinberg likewise had a strong interest in China.

But when these two men stepped down from their posts in 2011, China policy was left largely in the hands of National Security Advisor Tom Donilon and Kurt Campbell, the assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs. Donilon, though he had broad policymaking experience, had no particular China background or education. Campbell, meanwhile, was a recognized expert on Asia-Pacific affairs, but with a focus more on Japan. In part because of his perceived fondness for Tokyo, Chinese analysts viewed Campbell as overly hawkish and confrontational toward Beijing. To some, the problem was Campbell’s background in Soviet studies and U.S.-USSR relations, which caused him to view U.S.-China relations through an adversarial, Cold War-tinted lens.

Just as the Obama administration was rolling out its “pivot to Asia” policy, the administration lost two of its most influential China hands in Bader and Steinberg. The resulting dearth of China-specific expertise has led to the lack of grand strategic understanding that Becker saw in the intelligence community. For the world’s most important bilateral relationship, there’s a distinct lack of China scholars serving in top level positions (with the exception of Evan Medeiros, who assumed Bader’s old position on the NSC last year). And as Becker noted, a lack of understanding can drive misunderstandings and confused reactions and responses.

As a result, the administration seems to have underestimated the strength of Beijing’s reaction to the “pivot to Asia” policy. Many Chinese analysts insist that all of China’s “aggressive” moves in recent years are merely a direct reaction to the perceived threat from the U.S. Unfortunately, it seems the same confusion about Chinese strategic goals that Becker saw among the intelligence analyst community also colors higher levels of policymaking.

Which brings us back to Becker’s point: it’s not enough to simply spy on China. The U.S. intelligence and policymaking communities alike have to know what to do with the information the U.S. gathers. Similarly, to adequately defend its interest in the Asia-Pacific, it’s not enough to roll out new policies. Analysts must also be able to correctly predict the Chinese reaction based off of a sound understanding of Chinese goals and strategy. In a policymaking community that only recently began turning its attention to China, there is indeed an “information deficit” when it comes to understanding China.