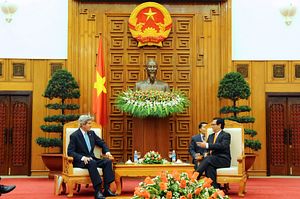

Nguyen Phu Trong, the Secretary General of the Vietnam Communist Party, will visit Washington from July 6-9 to mark the twentieth anniversary of the normalization of diplomatic relations between the Socialist Republic of Vietnam and the United States.

Trong’s visit is unprecedented because it marks the first time that the leader of the Vietnam Communist Party will visit the United States in an official capacity.

Diplomatic sources report that Vietnam lobbied for this visit and that one sticking point was protocol. The Vietnamese side wanted Secretary General Trong to be received by President Barack Obama in the White House. This created a protocol issue because Secretary General Trong has no counterpart in the U.S. political system.

Media sources report that Secretary General Trong will be received by Vice President Joe Biden in the The White House and that President Barack Obama will join in the discussions. There are rumors that Trong may meet with Hillary Clinton.

In 2013, Obama and his Vietnamese counterpart Truong Tan Sang signed an Agreement on Comprehensive Partnership. This is the key framework document for bilateral relations. Earlier this year Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter signed a Joint Vision Statement in Hanoi with his counterpart General Phung Quang Thanh that set out twelve areas of future defense cooperation.

The Obama-Trong meeting is significant because both leaders will be leaving office next year. Whatever understandings are reached during Trong’s visit will set the foundation for U.S.-Vietnam relations as leadership transitions play out in both countries.

Vietnam is scheduled to hold its twelfth national party congress in early 2016. This congress will adopt key strategic policy documents for the next five years. It is significant that since the HY981 oil drilling platform crisis in May-July last year, a number of members of the party Politburo have visited the United States, including Pham Quang Nghi (the party boss of Hanoi) and Tran Dai Quang (Minister of Public Security).

It is expected that Prime Minister Nguyen Tan Dung will make a sideline visit to Washington following his appearance at the annual meeting of the Untied Nations General Assembly in New York. Nguyen Sinh Hung, chairman of the Standing Committee of Vietnam’s National Assembly also is likely to make a visit according to the rumor mill.

Foreign analysts, in an attempt to make sense of Vietnam’s opaque decision-making system, have posited the existence of conservative and reformist wings in the Politburo. Secretary General Trong is often portrayed as an ideological conservative who favors close relations with China. Prime Minister Dung is viewed as a reformist who seeks closer economic and possible security ties with the United States. Dung is rumored to be seeking the post of party Secretary General at the 2016 national congress.

It is likely that factional alignments in the Politburo are more nuanced and complex. Personalities play a role. For example, State President Truong Tan Sang, a rival to Dung, is said to side with Trong. Sang is often put in the pro-China camp. But western diplomats who claim to know Sang well report that he can be very critical of China.

It is likely that factional alignments are more nuanced and complex. It is questionable whether anyone in the Politburo is pro-China or pro-America. It is more likely that they differ in assessing how to manage relations with the major powers without harming Vietnam’s national interest.

Vietnam cannot choose its neighbors and one enduring axiom of Vietnamese national security policy is to avoid having permanent tensions in relations with China. Vietnam pursues a multilateral approach in its relations with the major powers, this includes not only China and the United States, but Russia, India and Japan as well.

But in this framework at least two major questions arise in developing close ties with the United States: What will be China’s reaction? And can the U.S. be trusted to follow through on its commitments? The greatest fear held by Vietnamese national security analysts is that China and the United States might come closer together at Vietnam’s expense.

How does this play out in relations with the United States? Vietnam needs access to the U.S. market where it has a massive trade surplus. This counterbalances its massive trade deficit with China. But those who argue Vietnam should step up defense and security cooperation with the United States are countered by those who argue that the U.S. seeks to overturn the socialist regime in Vietnam by using human rights and religious freedom as levers to promote the “peaceful evolution” of Vietnam one-party state into a multi-party democracy.

Party members who fear China’s response to an uptick in U.S.-Vietnam relations rhetorically ask their party counterparts who favor closer ties with the U.S.: What has the U.S. done for Vietnam? They answer their own question by pointing to U.S. discrimination in arms sales and what they feel is the failure to address “the legacy of war” – Agent Orange (dioxin poisoning) and disposal of unexploded ordnance. These two issues were repeatedly mentioned in the U.S.-Vietnam Joint Vision Statement.

In other words, the U.S. should prove its good intentions by removing all International Trafficking in Arms Regulations (ITAR) restrictions on the sale of weapons to Vietnam. At present, U.S. policy is to sell weapons of a defensive nature to Vietnam – mainly related to maritime security and capacity building of the Vietnam Coast Guard – on a case-by-case basis. While the U.S. is addressing Agent Orange hot spots and assisting in the disposal of unexploded ordnance, some party members would like to see these efforts stepped up and better funded.

These issues surfaced during Carter’s visit to Hanoi. Vietnam’s Defense Minister called for the end of all restrictions on arms sales and the decoupling of arms sales from human rights issues. Nevertheless, Vietnam released Le Thanh Tung, a high-profile dissident, from prison on the eve of Secretary Trong’s visit as a sop to the United States.

Secretary General Trong’s visit to Washington and his meeting with President Obama will be read in Vietnam as recognition of the role of the Vietnam Communist Party in Vietnam’s political system. Trong’s visit will set the precedent for future visits by party leaders from Vietnam. To a certain extent Trong’s visit should assuage party conservatives – if the U.S. is seeking to overthrow Vietnam’s one-party regime by “peaceful evolution” then why is President Obama receiving the Secretary General of the Vietnam Communist Party?

The visit of Secretary General Trong and other members of the Politburo to the United States will assist them in their assessments of the future trajectory of bilateral relations and, more importantly, their evaluation of whether the U.S. can be counted upon to be a reliable partner. These assessments will feed into key strategic policy documents to be drafted and approved by the twelfth national party congress.

Two key outcomes of Trong’s meeting with Obama are likely to shape the future course of bilateral relations: Vietnam’s commitment to the Trans-Pacific Partnership and agreement to move forward and gradually step up defense trade (with the removal of all remaining ITAR restrictions). Vietnam would also be pleased if President Obama announced that he would fulfill his early pledge to do his best to visit Hanoi before his term in office expires.