On June 29, representatives of 50 countries gathered in Beijing to sign the legal framework agreement to establish the $100 billion Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Seven more countries are expected to sign, bringing the total number of founding AIIB members to 57. The institution will launch with China having a 30.4 percent share of the AIIB’s equity, followed by India (8.5 percent) and Russia (6.7 percent). The two notable absentees are the United States and Japan. Key NATO allies of the U.S., like Germany, France and the United Kingdom, have opted to join the AIIB. Germany will have the largest non-Asian stake (4.1 percent).

Of all its allies, why did only Japan stand with the United States on an issue with strategic implications? The new AIIB will symbolize China’s rise as a financial superpower, guiding the world’s biggest infrastructure financing institution. Whatever their reservations about China’s financial rise, most countries see it as a fact of life that cannot be stalled by staying out of the AIIB. They would rather be inside it, getting a share of the infrastructure orders that the AIIB will finance.

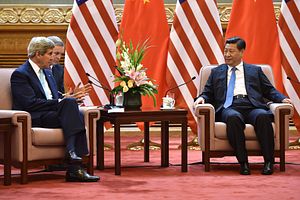

U.S. President Barack Obama says China may steer AIIB loans to meet political or strategic considerations rather than economic. So, the AIIB will have lower lending standards than existing multilateral institutions like the World Bank and Asian Development Bank, and undercut their effectiveness. Japan echoes this sentiment.

Why have other major donors shrugged away this objection? Because their diplomats smile at the notion that the World Bank or ADB have always had the highest lending standards. The U.S. as chief shareholder of the World Bank has always viewed it as a foreign policy tool. Ditto for Japan, chief shareholder of the ADB. Besides, as a development institution, the World Bank measures its success by its top line—lending volume—and not the bottom line. It has financed huge public sector undertakings of dubious quality across developing countries.

When I first worked for the Bank in 1985, one staffer explained to me the pressures to lend. “In the first quarter of the year, we promise to be really tough. By the second quarter, we worry that disbursements are behind schedule. By the last quarter, we are shoveling money as fast as possible. If we don’t meet disbursement targets, we risk losing allocations and staff next year.”

The Economist gave a delightful example of Bank lending as it really was in its issue of August 19, 1995:

Over the past few years, Kenya has performed a curious mating ritual with its aid donors. The steps are: One, Kenya wins its yearly pledges of foreign aid. Two, the government begins to misbehave, backtracking on economic reform and behaving in an authoritarian manner. Three, a new meeting of donor counties looms with exasperated foreign governments preparing their sharp rebukes. Four, Kenya pulls a placatory rabbit out of its hat. Five, the donors are mollified and the aid is pledged. The whole dance then starts again.

During the Cold War, the U.S. happily backed loans to Third World kleptocrats willing to toe U.S. foreign policy. One U.S. diplomat said of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s odious ruler and kleptocrat, General Mobutu, “He’s a son of a bitch, but he’s our son of a bitch.”

Bank projects in the Congo failed consistently. Why? Because aid to that country mostly ended up in Mobutu’s Swiss bank accounts. Many Third World dictators stole vast sums, yet in evaluating project performance, Bank staff were prohibited from mentioning corruption as a reason. Only after the Cold War ended was this taboo lifted. Bank President Wolfensohn (1995-2005) admitted that corruption had long been a major cause of failed loans, and pledged to curb it in future.

Will China similarly use its dominant position in the AIIB to promote its foreign policy aims, and wink at the peccadilloes of friendly governments? Of course. But this will be no more distortionary than World Bank behavior during the Cold War. That’s why so many countries are unworried about the AIIB’s lending standards, and have happily signed up. They acknowledge the emergence of China as a new financial power, and seek a slice of the economic action financed by that new power.

Obama sees the AIIB as a lending rival that will reduce the leverage the United States gets through domination of the World Bank. Japan has kept out of AIIB for the same reason: it too will suffer erosion of its leverage as chief financier of the Asian Development Bank. But other donor countries, long used to playing second fiddle to the U.S. and Japan in these two institutions, are just as willing to play second fiddle to China in the AIIB. Nothing personal, they will tell Obama, it’s just business.

The author is a Research Fellow at the Cato Institute.