With Chinese President Xi Jinping scheduled to visit the United States late this month, U.S. commentators and presidential hopefuls are debating whether Xi’s planned state visit should be downgraded or even cancelled. Organizers of the visit settled on the September timing knowing full well the presidential campaign would likely produce a toxic media environment. To understand Xi’s coming U.S. visit, one must look beyond the Beltway—at least as far as Manhattan.

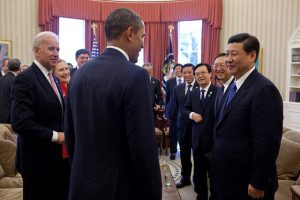

The White House is extremely unlikely to rescind the invitation for a state visit, which President Barack Obama reiterated by phone as recently as July. But even if it did, Xi would still be scheduled to address the 70th anniversary session of the United Nations General Assembly in New York on September 28.

This will be Xi’s first speech to the U.N. General Assembly, and it is no mere adjunct to the important business of dining with Obama in Washington. The U.N. anniversary comes at a time when the Chinese government is especially focused on history and is staging an enormous military parade to commemorate the end of World War II. Speaking at the United Nations gives Xi a prime opportunity to emphasize China’s declared role as a charter member and a co-founder of the post-war international order—a set of institutions and norms that many believe the Chinese government seeks to revise or replace.

Even if you take Chinese officials at their word that they do not seek to upend the international system, it is clear that the United States and China have differing approaches to the United Nations. In one respect, writes Princeton’s Thomas Christensen in his recent book The China Challenge, “China is a conservative force for protecting the twentieth-century rules of the international order. It is the United States, the Europeans, and Japan who are rewriting the traditional rules in the twenty-first century” (emphasis original). China’s strong stance on sovereignty and non-interference in internal affairs stands at odds with the comparatively new “responsibility to protect” doctrine, which calls for intervention in extraordinary circumstances.

For China, the U.N. anniversary is a major forum for demonstrating international leadership and staking out positions as the international system evolves. So U.S. observers should ask not whether China is becoming a “responsible stakeholder” in a U.S.-led evolution of international norms, but instead ask what Xi’s remarks represent for China as a strong, independent stakeholder in the evolving international system. You don’t have to like what you hear to learn from it.

Points West

Xi’s visit will likely take him far beyond the White House and the United Nations. The Des Moines Register reported Monday that Iowa Governor Terry Branstad said he hopes to meet with Xi and other governors in Seattle this month, suggesting that Xi will follow in the footsteps of previous Chinese leaders who have toured other parts of the United States.

For planners, travel beyond official summits and state dinners recalls Deng Xiaoping’s historic 1979 visit, which took him to a Texas rodeo. When Jiang Zemin in 1997 made the first U.S. visit by a top Chinese leader since 1985, he visited “Honolulu, Williamsburg, Washington, Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Los Angeles” and gave a speech at Harvard. Jiang also visited President George W. Bush in Crawford, Texas, in 2002. More recently, Hu Jintao visited Seattle and gave a speech at Yale in 2006, and in 2011 he stopped in Chicago, producing some friendly video from a visit to a high school. Xi is already experienced in this respect. As vice president in 2012, he visited the Iowa family who had hosted him during a 1985 exchange.

Though not confirmed, a stop in Seattle would mean a visit to a state where China has diverse investments, especially in high-tech, and it would steer clear of key U.S. presidential primary states.

Ambition or Caution

Xi’s agenda in the U.S. capital, meanwhile, is at least as unclear as his broader itinerary for the visit. This visit is under scrutiny partially because Xi is expected to enjoy the traditional state visit honors of an arrival ceremony (here’s Hu Jintao’s) and a state dinner, but how much time Xi and Obama will spend together, and in what format, has not been announced.

The presidents likely plan to deliver some good news on bilateral cooperation, perhaps highlighting plans for climate cooperation leading up to December’s U.N. Climate Change Conference in Paris and announcing incremental progress toward a bilateral investment treaty. The relatively sparse news from June’s Strategic and Economic Dialogue left room for significant announcements by the presidents. Still, this all could be taken care of in a single day; a real summit of any significance would take more time.

Both governments should be judged by whether they seize this opportunity to acknowledge challenges posed by changes in the global power balance and to counteract dangerous currents in the bilateral relationship and in both countries’ domestic politics. If the presidents celebrate a few cooperative efforts but can’t make progress in managing conflicts over economic espionage, cybersecurity, the South China Sea, human rights, and international norms, there wasn’t really all that much to downgrade in the first place.

Graham Webster (@gwbstr) is a researcher, lecturer, and senior fellow of The China Center at Yale Law School. Sign up for his free e-mail brief, U.S.–China Week.