I learned of an irony in policymaker tendencies during my tenure in the Pentagon.

On the one hand, policymakers want options. They want to retain a sense of agency over events and usually believe the decisions they make matter. On the other hand, they tend to be woefully biased in favor of crises and short time horizons; long-term or “strategic” decisions can often wait. The latter, of course, imposes quite a bit upon the former. By punting on decisions—often for fear of taking a risk—policymakers usually end up narrowing options for themselves and their successors. Reluctance to settle on a decision frequently reduces the choices available in the future when they (or their successors) are eventually boxed into having to make a choice. The effects of time are perhaps the thing most neglected in decision-making.

We’ve been in just such a dilemma with North Korea for decades. As I detail in my forthcoming book, nearly every U.S. administration going back to the days of President Lyndon Johnson has opted for de-escalation through conciliatory diplomacy when faced with a crisis on the Korean Peninsula, even when they talk tough or flex military muscle after a crisis has cooled. Retaliation in various forms was always on the table for discussion at the National Security Council, but U.S. decision-makers were historically paralyzed by the possibility (no matter how large or small) of inadvertent war. And after North Korea went down the path of developing nuclear weapons, no U.S. president was willing to take any immediate risks to stop it.

As a consequence, each president handed his successor a worse Korean Peninsula situation than he inherited. The one exception might be the handover from Bill Clinton to George W. Bush, but even that’s endlessly debatable. North Korea is now infamous in policy circles for being the “land of lousy options,” and the U.S.-South Korea alliance is careening toward a future of limited wars with a nuclear-armed adversary.

This wasn’t inevitable; it was the result of buckpassing from administration to administration.

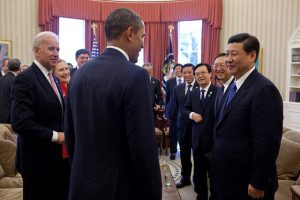

Today the United States finds itself in a similar situation with China. Extreme policy options that involve discernible risks and opportunity costs—such as appeasement or war—seem rather unlikely given the endless deliberation that’s preceded even minor decisions about the South China Sea. Nobody wants rash or uncounseled decision-making of course, but indecisiveness has consequences too.

Yet, as with the Korean Peninsula, merely continuing status quo policy dynamics with China gradually chips away at America’s professed goal of maintaining a stable, liberal regional order. That’s because China’s illiberal foreign policy interests—and commensurate military capabilities—are expanding. It continues to militarize its artificially constructed islands in the South China Sea. And, as my colleague Jeff Reeves’ recent book explains, its use of economic interdependence with its neighbors has become a routine coercive tool for political gain. These combined trajectories pose geopolitical, warfighting, and normative challenges to the United States and its allies.

The United States is long overdue to pursue active, thoughtful “shaping strategies” that respond to regional sensitivities while conditioning the security environment in a way that gives future U.S. presidents a policy portfolio with better options than history suggests is likely. But rather than trying to shape China’s choices, as Tom Christensen and others might advocate, the United States is likely to have more success shaping the strategic situation; patterns of regional behavior, the regional distribution of capabilities, and habits of cooperation in conjunction with smaller powers. Create an environment inhospitable to even China’s worst choices.

There’s too much to say about “shaping strategies” to outline here without veering off of the primary point: If status quo trends hold into the future, and U.S. policymakers take comfort in claiming that China policy didn’t go awry on their watch—as past ones have done with North Korea policy—fewer and more extreme options may be all that remains on the table in the not-too-distant future.

North Korea was bad enough. The stakes are much higher with China.

The views expressed belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, DKI-APCSS, or the U.S. Government.