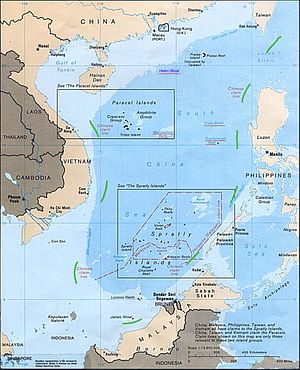

On Monday, the Philippines finished presenting its arguments on the South China Sea issue before an international tribunal in The Hague. The Philippines, as Diplomat readers know, filed an arbitration case against China on the South China Sea issue in 2013, seeking clarity on the legality of China’s nine-dash line, the status of certain features in the South China Sea, and the Philippines’ own maritime rights in the disputed region. Arguments on the merits of the case opened on November 24.

On November 30, Philippine Secretary of Foreign Affairs Albert del Rosario wrapped up the Philippine position in his concluding remarks. In the speech, del Rosario praised the power of international law to bring clarity to the disputes. He also accused China of “failing” to uphold international law.

“China’s unilateral actions, and the atmosphere of intimidation they have created, are… trampling upon the rights and interests of the peoples of Southeast Asia and beyond,” del Rosario said.

The Philippines, as I’ve written before, frames its arbitration case as a test for the principle of “right vs. might.” That rhetoric was on full display in del Rosario’s speech, as he defended Manila’s use of arbitration “to provide all parties a durable, rules-based solution.”

China has criticized the arbitration process as “a political provocation under the cloak of law,” as Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying put it on Tuesday. “China will not accept any solution imposed on it or any unilateral resort to a third-party dispute settlement,” Hua said, predicting that the case “will lead to nothing.”

Del Rosario, however, told the tribunal that the arbitration was the path of last resort for the Philippines. “With an assertiveness that is growing with every passing day, China is preventing us from carrying out even the most basic exploration and exploitation activities in areas where only the Philippines can possibly have rights,” he said, explaining why “we so desperately need” the tribunal’s guidance.

Del Rosario also painted the case as not only meaningful for the Philppines, but as a test of the fundamental principle of international law – in this case, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, or UNCLOS – applying equally to all states. He implied that if China’s actions are left unchallenged, UNCLOS will be reduced to “the quaint aspiration of a time now past.”

“No State should be permitted to write and re-write the rules in order to justify its expansionist agenda,” del Rosario proclaimed. “If that is allowed, the Convention itself would be deemed useless… the rule of law would have been rendered meaningless.”

On the substance of the case, del Rosario said that the Philippines’ arguments demonstrated “that the regimes of the continental shelf and exclusive economic zone under UNCLOS, and even general international law, plainly exclude China’s claim of “historic rights” within the nine-dash line.”

He also sternly criticized China’s island-building in the South China Sea, calling the work evidence of China’s “utter disregard for the rights of other States, and for international law.” Beijing “is intent on changing unilaterally the status quo in the region, imposing China’s illegal nine-dash line claim by fiat and presenting this Tribunal with a fait accompli,” del Rosario argued.

China has repeatedly defended the construction of artificial islands, as well as the new facilities being built upon them as within China’s sovereignty and compatible with international law. “China’s normal construction activities on our own islands and in our own waters are lawful, reasonable and justifiable,” the Foreign Ministry said in March. China also argues that its construction is mainly for civilian use, and points to construction work done over the years by Vietnam and the Philippines as precedents.

Del Rosario urged the tribunal to side with the Philippines’ argument that none of the features in the Spratlys – including Itu Aba, the only island with naturally occurring fresh water – can generate a 200 nautical mile exclusive economic zone. “[T]here is no greater contribution to international peace and security the Tribunal could make than to decide that none of the features in the Spratly Islands is capable of generating any entitlement beyond 12 [N]M,” he said.

If the tribunal determines that any of the features is entitled to more than a 12 nm territorial sea, del Rosario argued, “it would convert the nine-dash line, or its equivalent in the form of exaggerated maritime zones for tiny, uninhabitable features, into a Berlin Wall of the Sea.” The Philippines would thus be excluded from accessing any of the resources within its own EEZ, he said.

With the arguments closed, the only thing left to do is wait for the tribunal’s response. A ruling is expected in mid-2016. The Philippines (and China, no matter how much it denies it) won’t be alone in closely following the developments: Australia, Indonesia, Japan, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam all sent observers to the proceedings, and Japan and the United States has expressed support for using legal means to settle the disputes. Though China has been steadfast in its intention to ignore the ruling, a decision in the Philippines’ favor could change how other claimants — including Vietnam, Brunei, Malaysia, and Taiwan — approach the South China Sea issue.