On his first visit to Beijing, then-Armenian defense minister Vazgen Sargsyan is said to have thrown the hosts into a state of mild confusion when he remarked that (paraphrased) “as we say in Armenia, together with the Chinese there is more than a billion of us.” Jokes and linguistic barriers aside, the comment reflected the main motivating factor behind Armenia’s outreach to China. When dealing with larger and often hostile neighbors, it is only natural for small countries to seek out support or, as a paper published by the Armenian government’s think tank put it, a “special partnership,” externally.

The Caucasus, hemmed in by Russia, Turkey, and Iran, is particularly rife with conflicts. Armenia and Azerbaijan are engaged in low-intensity attrition warfare with non-existent bilateral relations. Turkey has largely sided with Azerbaijan and kept its economic ties with Armenia to a minimum. This leaves Armenia reliant on Georgia, itself in conflict with Russia, and Iran, which until recently faced international sanctions. While Azerbaijan is in much less restricted geopolitical position, its relations with Iran, as well as Russia, have also been quite testy.

Although Armenia’s, as well as Azerbaijan’s and Georgia’s, expectant gaze has historically been directed west and north, their long history includes important precedents for reaching out east as well. Perhaps the most remarkable episode is from the 13th century when in the aftermath of European setbacks in the Crusades and advances by the Abbasid Caliphate, the Armenian kingdom accomplished a quite dramatic diplomatic feat. Armenia’s “defense minister” and the king’s brother Smbat Sparapet sealed a military alliance with the Mongol Khan after traveling more than 5,000 kilometers to his seat at Karakorum. Armenian King Hetum himself undertook the trek five years later. Although relatively short-lived, that pact resulted in the defeat of the Caliphate and the sacking of Baghdad, in which both Armenian and Georgian forces, along with Chinese artillery experts, aided the Mongol army.

Historical precedents like these are never far from the minds of both the Caucasus and Chinese officials. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s major foreign policy and trade initiative in Eurasia recalls the ancient Silk Road. Incidentally, Armenian merchants played a prominent role in the history of China-West trade, both overland and through Canton and the Indian Ocean.

The current decade has seen China emerge as one of the top trade partners for Armenia and the other two Caucasus states. There has been a notable increase in Armenian exports to China, from just $16 million in 2011 to $171 million in 2014. By comparison, Armenia’s exports to neighboring Iran amounted to half of that volume. Also by 2014, exports from Georgia and Azerbaijan to China grew to $90 million and $46 million, respectively. Georgian, Azerbaijani and Armenian imports from China amounted to $820, $509, and $417 million, respectively.

While the combined $2 billion in trade turnover may only be a speck for the world’s largest economy, it is quite substantial for the Caucasus trio. Highlights of cooperation include Armenia’s chemical industry, automobile assembly in Azerbaijan, and banking and construction in Georgia.

Cultural and educational exchanges have also proliferated. Chinese-funded Confucius Institutes were established in Yerevan in 2009, Tbilisi in 2010, and Baku in 2011. The institutes have facilitated study in China and last year a Chinese Armenian organization began to offer scholarships for Chinese students to study in Yerevan. Construction of a Chinese language high school is currently underway in Armenia’s capital.

In 2015, the Caucasus states continued active courting of Chinese interest with leaders of all three countries visiting Beijing, while a delegation led by Chen Changzhi of the National People’s Congress went to Tbilisi and Yerevan. In Armenia, the Chinese government supported the Armenian Genocide centenary commemorations by gifting 40 tons of equipment to ensure their live international broadcast. China had previously extended other forms of aid to Armenia, most prominently public buses and ambulances. Chinese aid has been extended to Georgia and Azerbaijan as well.

Perhaps the most symbolically significant technology transfer between China and the Caucasus occurred in the aftermath of the aforementioned visit by the Armenian defense minister. In 1999 Armenia acquired – reportedly on favorable terms – Chinese NORINCO WM-80 multiple-launch rocket systems in what became the first Chinese military sale in the Caucasus and also Armenia’s first major weapons acquisition from outside the former USSR. In 2013, reports surfaced of further Armenian purchases of Chinese missile artillery.

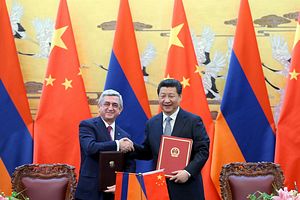

During his March 2015 visit to China, Armenian President Serge Sargsyan emphasized the importance of continued bilateral military cooperation. The point was also stressed by the presence of Armenia’s first deputy defense minister David Tonoyan at the sixth Xiangshan Forum, co-sponsored by the China Military Science Society (CMSS) and the China Institute for International Strategic Studies (CIISS), in October.

Predictably, Azerbaijan has in the past protested this cooperation but more recently Baku has expressed its own interest in the purchase of Chinese weapons systems, particularly those already acquired by Pakistan and Turkey.

Both Armenia and Azerbaijan also expressed interest in becoming observers in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a regional security forum led by China and Russia. This mutual interest is notable in particular since, unlike Armenia, Azerbaijan has so far declined to join Russian-led security and economic organizations, namely the Collective Security Treaty Organization and the Eurasian Economic Union, instead joining the Non-Aligned Movement several years ago (Armenia and China have an observer status at NAM). Georgia, for its part, remains focused on working toward NATO membership.

In spite of their divergent foreign policies, all three Caucasus states are committed to the “one-China policy” and attempt to court Beijing’s political support. China has remained politically neutral in the dispute between Armenia and Azerbaijan, pointedly abstaining during a vote on the Karabakh conflict at the UN General Assembly in 2008. The same year, China notably refused to back Russia in its conflict with Georgia. The Caucasus will certainly remain on the margins of China’s interest, but will continue to receive some attention as Beijing’s global profile rises.

China is far enough from the Caucasus not to be perceived by its states as a security concern in the foreseeable future. Instead, with plenty of threats evident to leaders of Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia closer to home, China is pursued as a major global partner that could have a stabilizing regional effect. Military cooperation with China appears to be of greater interest to Armenia than the two other states, but attracting economic cooperation and investments remains an overarching priority in their relations with China for all three Caucasus countries.

Emil Sanamyan writes about the politics and security in Eurasia with a focus on the Caucasus. He is based in Washington, DC area and tweets @armen_reporter